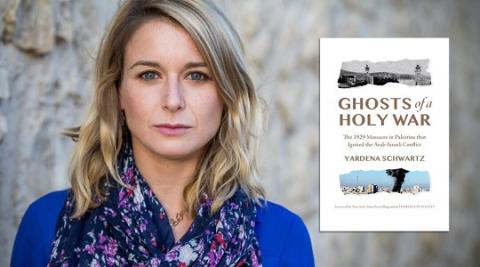

Ghosts of a Holy War

That day in Hebron, 67 unarmed men, women and children were slaughtered; dozens were wounded. A total of 133 Jews were murdered and hundreds more wounded as the riots spread across the Mandate. The British, underprepared and caught by surprise, extracted Hebron’s surviving Jews in armored cars and told them not to return. “For the first time in nine centuries,” Yardena Schwartz writes, “the City of Abraham was a city without Jews.”

In “Ghosts of a Holy War,” Ms. Schwartz calls the Hebron massacre the “ground zero” of what would become the Israel-Palestine conflict. The author, an American journalist who has lived in Israel, traces a “direct line” between Hebron in 1929 and last year’s Hamas-led invasion of southern Israel from Gaza: “The forces that drove Arabs in Hebron to slaughter their Jewish neighbors in 1929 were identical to the forces behind October 7.”

The 1929 rioters believed false claims that “the Jews” wanted to destroy the Al Aqsa Mosque. Hamas, in 2023, code-named its rampage “Operation Al Aqsa Flood.” In 1929, as in 2023, Arabs in Palestine hailed the killers as heroes while simultaneously celebrating and denying their atrocities. In 1929 the British rewarded terrorism by reducing Jewish immigration into the Mandate. In 2023 the Biden administration led the international chorus calling for negotiations on a Palestinian state. “Ghosts of a Holy War” is bookended by these two detailed accounts of mass murder. In both cases, the sadism—rapes, decapitations, the torture of children, the mutilating of genitals—is harrowing.

Ms. Schwartz’s account of the prelude to the 1929 massacre makes good use of the letters of David Shainberg, who was born in Tennessee and had enrolled at the Hebron Yeshiva in 1928 at the age of 22. Shainberg, who thought secular Zionism a “worthless anti-Jewish cause,” wanted to study Torah close to Hebron’s Tomb of the Patriarchs, where, the Book of Genesis records, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob are buried. The Jews and Arabs of Hebron got on well enough, but the power balance that favored Islam meant that the closest that Jews could get to their shrine was the seventh step of its exterior staircase. Zionism threatened to upend first this Islamic supremacy and then the population balance that favored Arabs. Shainberg was murdered in the 1929 riot.

The human dimension is more complex than the religious one and a frail source of hope for Ms. Schwartz. Many of Hebron’s Arab policemen joined in the 1929 slaughter, but some two dozen Arab families, she notes, “risked their lives to save at least half the Jews in Hebron.” The central section of “Ghosts of a Holy War” describes the erosion of this human middle ground over the following decades.

Haj Amin al-Husseini, the pro-Nazi Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, did more than anyone (barring his protégé and distant cousin, Yasser Arafat) to shape the dysfunctionality of Palestinian nationalism. One of the saddest threads in this tragic story comes when Ms. Schwartz seeks out the descendants of the good neighbors of Hebron. They are unwilling to talk. “In Palestinian society,” she explains, “being labeled a collaborator with Israel is a death sentence.”

The conflict is often explained as a particularly vicious real-estate dispute or a struggle between modern nationalists. Such disagreements can be resolved by compromise, so this explanation appeals to outsiders, atheists and the conflict-averse. Yet the Jewish victims of 1929 were not Zionists or anti-Arab. They were anti-Zionist yeshiva students or members of an ancient Sephardic population that, like their Arab neighbors, had yet to assume a modern political identity. Similarly, the victims of 2023 were not settlers. They were the kind of Israelis most likely to favor compromise and cohabitation: kibbutzniks, peace activists, leftists and Arab Israelis.

Ms. Schwartz argues that the conflict originates and continues in the “religious dimension.” Palestinian nationalism, she observes, did not exist in any coherent sense in 1929. There was no State of Israel then, and Jews were a minority within its future borders. This was before the post-1967 military occupation of Judea and Samaria (the West Bank), which would return Jews to Hebron (as settlers). Then, as now, she argues, an Islamic-inspired refusal to live in equality with Jews produces jihadism (“holy war”). She also argues that it radicalizes the survivors.

After Hebron, the Mandate’s Jews realized that the British could not protect them; the first Sephardic volunteers joined Zionist militias. The Zionist leadership, which had developed a protostate under British supervision and still hoped for an accommodation with the Mandate’s Arabs, became more hostile to both Britain and the Arabs. The Arabs, who saw the Mandate as a piece of Syria, started to redefine themselves as “Palestinians.” The British responded by rushing a “colonial army” to the Mandate, which would eventually be attacked first by the Arabs and then by both Jews and Arabs.

Back in 1929, Ms. Schwartz writes, Hebron’s Sephardic men were “friends and business partners with their Arab neighbors.” They “drank Turkish coffee, smoked hookah, and played backgammon in one another’s homes.” Today, Hebron is divided into sectors controlled by the Israeli army and the Palestinian Authority. The Palestinian mayor is a convicted terrorist who tells Ms. Schwartz that Jews have no historical connection to the Holy Land. The Israeli settlers live under armed guard. “Ghosts of a Holy War” is a good book about a bad mess. The winner will take all, or whatever is left.

Dominic Green