The Jewish Identities of European Jews: What, Why and How

The findings are based on data collected from more than 16,000 Jews living in 12 countries in the European Union at the time of the survey.

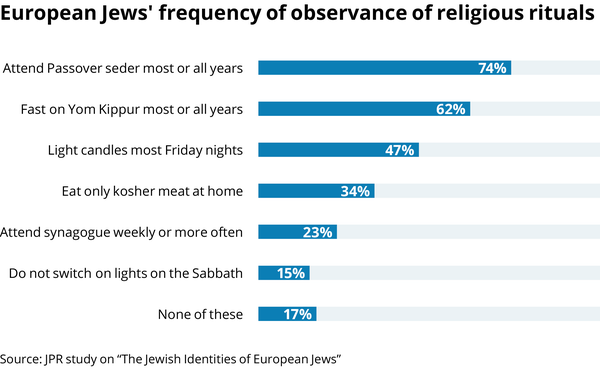

While most European Jews attend a Passover seder and fast on Yom Kippur, they do not attend synagogue regularly, eat kosher food or keep Shabbat. According to the findings, younger European Jews are far more likely to be Orthodox or ultra-Orthodox than their elderly counterparts.

A country comparison shows that Belgium has the highest share of Orthodox Jews in Europe, while Spain the highest share of Reform Jews.

The findings are based on data collected in 2018 – as part of a study commissioned by the EU on Jewish perceptions and experiences of antisemitism – that was never previously published. The data analysis was conducted by Prof. Sergio DellaPergola, widely known as the dean of Jewish demographers, who serves as chairman of the JPR’s European Jewish Demography Unit, and Dr. Daniel Staetsky, a senior research fellow at JPR and director of its European Jewish Demography Unit.

The data was collected in the following countries: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Of these, France and the U.K. have the largest Jewish communities and Denmark the smallest.

“There is a great deal of food for thought here, with potentially significant implications for Jewish education and community development going forward,” said Dr. Jonathan Boyd, executive director of JPR, in a statement announcing the release of the study.

Here are some of the key findings:

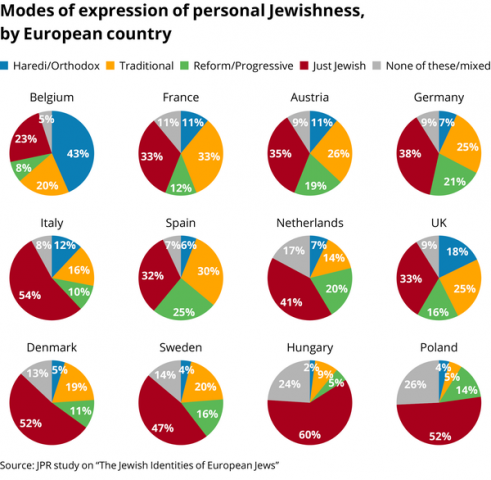

■ Among European Jews, 5 percent identify as Haredi (ultra-Orthodox), 8 percent as Orthodox and 15 percent as Reform/Progressive. The majority, however, do not identify with any of these denominations. Indeed, topping the list of “modes of expression of personal Jewishness” is “Just Jewish” (38 percent), followed by “traditional” (24 percent).

By contrast, according to a recent Pew Survey of American Jews, published in May, a vast majority of American Jews (63 percent) identify with one of the following three denominations: Reform (37 percent), Conservative (17 percent) and Orthodox (9 percent). Younger European Jews (ages 16 to 29) are more likely to be religiously observant than older European Jews (70 and over). Indeed, 22 percent of young European Jews identify as either Haredi or Orthodox, compared with only 5 percent of older European Jews – who are far more likely to identify as “Just Jewish” (49 percent).

The study found striking differences in this regard among the 12 countries. Whereas Haredi Jews account for 31 percent of the total Jewish population of Belgium (owing mainly to their large concentration in Antwerp), they comprise less than 1 percent of the Jewish populations of Denmark, Sweden and Spain. Orthodox Jews account for about 10 percent of the total in Belgium, France, Italy and the U.K., but only 1 percent in Hungary. Progressive/Reform Jews, meanwhile, account for 20 percent or more of the total in Spain, Germany and the Netherlands, but only 8 percent in Belgium and 5 percent in Hungary.

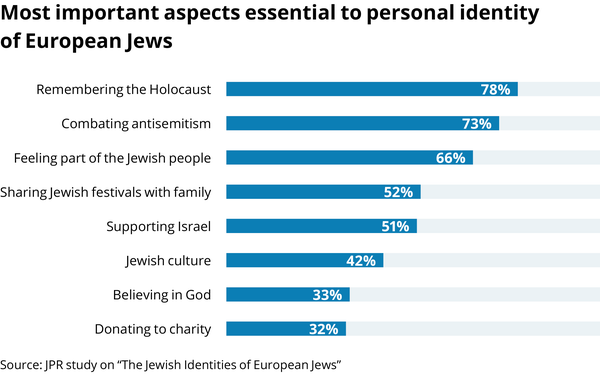

■ “Remembering the Holocaust” and “combating antisemitism” top the list of the most essential elements of European Jewish identity. When asked which aspects of their Jewish identity were “very important” to them, 78 percent of the respondents checked “remembering the Holocaust” and 73 percent checked “combating antisemitism.”

A little over half of the respondents (51 percent) checked “supporting Israel” (about the same percentage as “sharing Jewish festivals with family”), whereas only a third checked “believing in God” (about the same fraction as “donating to charity”).

■ Even if they do not lead religious lives, European Jews are more likely to see themselves as a religious minority than an ethnic minority. In the survey, respondents were asked whether they considered themselves to be Jewish on the grounds of their religion, culture, upbringing, ethnicity, parentage or any other reason. Among those who checked a single answer, religion was the top choice (35 percent), followed by parentage (26 percent), culture (11 percent) and heritage (10 percent). Only 9 percent of the respondents checked ethnicity (with another 3 percent checking upbringing).

Respondents in the U.K., Belgium, Italy and Spain were more likely to describe themselves as Jewish by religion than respondents in Hungary, Poland, Sweden and the Netherlands.

■ Among European Jews, Belgians possess the strongest Jewish identity and Poles the weakest. Respondents were asked to rate their level of Jewish identity on a scale of one to 10. The average score in Belgium was 8.8, while in Poland it was 6.4. Next in line after Belgium were Spain and Italy (both 8.3), France (8.1) and the U.K. (7.9).

■ A majority of European Jews attend a Passover seder and fast on Yom Kippur, but only a minority observe other key Jewish rituals. The study found that 74 percent attend a seder most years, 62 percent fast on Yom Kippur most years, but only 47 percent light Shabbat candles most Friday nights, 34 percent eat only kosher meat at home, 23 percent attend synagogue weekly or more often, and 15 percent do not switch on lights on Shabbat.

■ In Austria, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands, a slightly higher proportion of Jews are attached to Israel than to the country where they live, while in Denmark, France, Hungary, Poland, Sweden and the U.K., attachment to their own country is higher than to Israel.

Among the factors that could explain the greater attachment to Israel in the first group of countries, the study’s authors note, is the relatively large number of recent immigrants “whose degree of acculturation may not yet have reached the levels they likely will over time.”

Judy Maltz