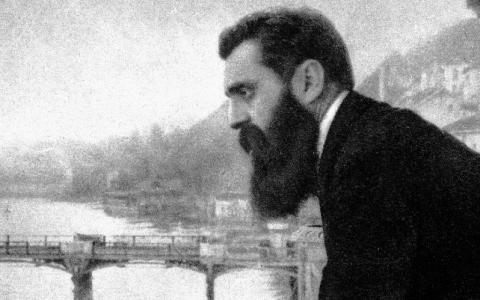

A new book about the father of Zionism Theodore Herzl

According to “Theodor Herzl: The Charismatic Leader,” a newly-released biography by historian Derek Penslar, Zionism’s founder struggled with an artistic temperament, often facing bouts of melancholy and what would today be described as manic episodes. Penslar, who is the William Lee Frost Professor of Jewish History at Harvard, describes his approach as unique in several regards. He told The Times of Israel that his book is “the first postmodern biography of Herzl,” characterizing its subject as a figure who meant “different things to different people, changing quite a bit across time and across space.”

It is the most recent volume in the Jewish Lives series by Yale University Press, and the latest of many biographies on Zionism’s founder written over the decades. “Theodor Herzl: The Charismatic Leader” seeks what its author calls “a middle ground between biographies presenting Herzl as a saintly figure and those pointing out his many flaws.” For Penslar, “it was precisely these flaws, these aspects of his personality that were so troubling to him, that made him great as a political leader.”

Penslar said that the book is also “a study on charisma itself,” noting its subject’s “charismatic effect on a large number of people, especially Jews.” He cites the intrinsic and extrinsic qualities that powered Herzl’s charisma — “sadness in his face, death in his eyes, force of personality, the power of his leadership ability, an indefatigable work ethic.”

Herzl was a writer, not a president or prime minister, but nevertheless founded “a new national movement,” Penslar said. He wrote the influential 1895 Zionist pamphlet “Der Judenstaat” (The Jewish State) and assembled a diverse coalition of Jews for the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland, in 1897. Herzl was even compelling enough to win audiences with world leaders or their representatives.

Walking in Herzl’s footsteps

Charisma had its limits. He did not secure recognition from a great power for a Jewish national home in Palestine, although he came close to an alternative in East Africa. He did not solicit the local population of Palestine itself, either Arab or Jewish, preferring to envision a dream version in his 1902 novel “Alt-Neuland” (Old-Newland).

Herzl is widely quoted in the biography, including his “Alt-Neuland” statement, “If you will it, it is no dream” — although Penslar translates the words as “fairy tale” rather than “dream.”

Penslar has traveled with family to Israel’s Mt. Herzl, where he has gone on walks, excursions to the Herzl Museum, and visits to the gravesites of Herzl and most of his family, along with those of the Jewish state’s founders. He cites Herzl’s ubiquitous image in Israeli classrooms and currency. Penslar also notes a more lighthearted treatment in Israel — “Herzl as a hipster, a hip Herzl, with a cool hipster beard, an earring, in cool 20th-century clothing. He’s become a meme.”

Hipster Herzl does not appear in the book, but the frontispiece features a photo of Herzl with his wife Julie and mother Jeannette that indicates his tumultuous personal life. “I don’t think anyone’s ever seen it,” Penslar said. “It’s the only one with his wife and mother together in some form. They disliked each other so much.”

Researching Herzl’s multiple diaries and 6,000 letters, “I found some things people had not used,” Penslar said, including correspondence between Herzl and the editors of the Vienna-based newspaper for which he worked, Die Neue Freie Presse, and between Herzl and Max Nordau, his closest friend in the Zionist movement.

Herzl had a demanding day job for Die Neue Freie Presse — first as its Paris correspondent, where he reported on the Dreyfus Affair, then as its literary editor. Penslar said that it is “really important for anyone reading about Herzl’s life” to understand that “all his Zionist activities” were done “in his spare time.”

Herzl’s wide-ranging external life was accompanied by inner turmoil. “He documented his own depression,” Penslar said. “You don’t have to read into it. [He wrote] quite openly about melancholy. He had periods of elation. Today, you might call it mania.”

Born in 1860 on Dohany Utca in the heart of the Jewish community of Pest, Hungary (now Budapest), young Herzl was deeply affected by the deaths of his sister Pauline and a young woman named Madeleine Herz. “He never got over his sister’s death,” Penslar said, “and claimed to have had a deep love for [Herz]. I think that the combination of the two [losses] certainly had an effect.”

Penslar describes Herzl’s eventual marriage to Julie Naschauer as “a very bad marriage.” He said both partners were troubled, and that while Herzl loved their three children, Paulina, Hans and Margaritha, “most of the time he was an absent parent,” engaged in Zionist activity.

“Political leaders are often troubled people,” Penslar reflected. “[Herzl] had unusual problems, unusual hunger, unusual ambition. In that sense, Herzl is not atypical of people who become great political leaders.” The author calls him “hungry for some kind of acclaim. He had a really deep-seated sense of depression and failure. He was looking for something to give great meaning and value to his life.”

How do you solve a problem like anti-Semitism?

That “something” was the Zionist movement. Penslar said that while Herzl was “not an observant, learned Jew,” he “certainly knew he was Jewish,” and by the early 1890s “he began to think about alternatives that might solve the problem of anti-Semitism.”

Herzl promoted one such alternative — a Jewish national home — in Der Judenstaat. This work denounced both anti-Semitism and the oppression of the working class. It connected Herzl with an international movement creating Jewish settlement in Palestine, then ruled by the Ottoman Empire. Herzl overcame his reluctance to adopt an increasingly used term: Zionism.

Although Herzl could not attract support from great Jewish philanthropists of the era, he used his charismatic leadership to assemble a diverse coalition of his people. Orthodox and secular, Central and Eastern Europeans, Yiddish speakers and Hebrew revivalists all came together for the First Zionist Congress in Basel.

“The Zionist Congress was a kind of space the world had not seen before,” Penslar said. “It was largely, really, his work alone.”

Penslar noted that Herzl had to deal with “very powerful personalities” and “different ideological views,” including revered poet Asher Ginzberg, better-known by his Hebrew pen name Ahad Ha’am, who “dismissed him as a fool with no Judaic learning.”

Also, not all Jews supported Zionism. “Most Jews of the time did not ignore anti-Semitism, but did not have a solution like Herzl had in mind,” Penslar said, adding that they considered him “myopic at best and dangerous at worst”.

Unlikely court Jew

Herzl also engaged in high-level diplomacy, meeting such personages as Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II, German Kaiser Wilhelm II, and British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain. The latter offered a Jewish homeland not in Palestine but in a section of British East Africa that was then called Uganda, but is part of Kenya today. Calling such meetings extraordinary, Penslar nevertheless said that Herzl “was never close to getting what he wanted.”

Penslar said that Abdulhamid was uninterested in giving Herzl “any kind of concession in Palestine or any part of the empire,” and only wished to assess Herzl’s usefulness in helping the Ottomans escape indebtedness to European powers.

The historian also described Wilhelm as an anti-Semite who was potentially intrigued by an “idea to get the Jews out of Europe.” Nevertheless, Herzl made his sole visit to Palestine in October 1898 after learning that Wilhelm would be there. His 10-day itinerary included two meetings with the kaiser — one at the Jewish agricultural school of Mikve Israel, and one outside Jerusalem. Penslar said that Herzl “was not terribly impressed” with Palestine and “particularly unimpressed by Jerusalem, which he felt was dirty and not up to Western standards.”

Herzl did not seek out the local population of Palestine — neither its Arab majority, which totaled 90 percent, or its 30,000 Jews, which created a slight majority in Jerusalem. Penslar said that Herzl “displayed no interest in the culture or people of the region,” reading up on area botany but “not about the people who lived there, not Islam, not holy sites to Islam.”

“He had a kind of vision of Zionism in his mind that had very little to do with what Palestine was actually like at the time,” Penslar said.

Hints of that vision exist in “Alt-Neuland.” The title refers to a future, socially progressive Jewish state in Palestine. Its creation results in “solving the Jewish problem,” Penslar said. “Jews live in comfort and safety. There is no anti-Semitism left in the world… [Herzl] really believed the Zionist movement would be a model to the world in terms of social progress and equity.”

Premature death and legacy

Herzl could not resolve intra-Zionist dissensions that wore him down, and died prematurely at age 44 in 1904, more than four decades before the establishment of the State of Israel. Penslar said that it is “hard to know exactly what was wrong,” but added that Herzl was diagnosed with a heart ailment at age 35, and that in his late 30s and early 40s he complained of palpitations, fatigue, fainting spells and shortness of breath.

“All are indicative of heart failure,” said Penslar, who showed his manuscript to several physicians. Herzl’s immediate family all died prematurely as well. His last surviving child, Margaritha, nicknamed Trude, perished with her husband at Theresienstadt. Their son, Herzl’s lone grandchild, Stephan Neumann, changed his name to Stephen Norman and committed suicide in 1946 after learning that his parents had died.

Today, the well-known Mount Herzl is its namesake’s final resting place. Yet the book cites a statistic that only about half of all young Israelis know who he was. “People know him as somebody famous, somebody important, but the more specific context is fading,” Penslar said.

The author hopes his book will be published in Hebrew so it may inspire “renewed understanding of his greatness, the personal qualities of greatness coming from a troubled, even tormented person.”

Rick Tenorio