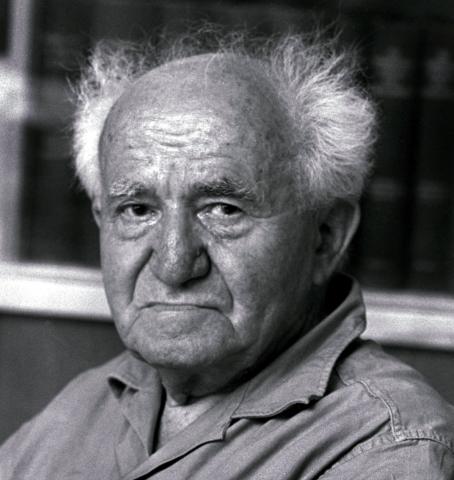

A state at Any Cost: the life of David Ben-Gurion

Nothing came of this proposal and, on Nov. 29, 1947, the United Nations voted to partition Palestine into Arab and Jewish states. Full-scale fighting broke out six months later.

Ben-Gurion’s 11th-hour meeting is one of the little-known facts revealed by the Israeli historian Tom Segev in his deeply researched, engrossing and, in some respects, controversial biography, “A State at Any Cost.” Segev has written several books on Israel, and he joins other noted experts who have mined newly released archival sources to re-examine the life and legacy of the country’s first prime minister. The timing makes sense: As Israel has transformed itself from a small, struggling society into a high-tech player on the global stage, its people have become increasingly interested in the ideals that first guided it and the roots of problems that still confound it. And, like America’s founding fathers, David Ben-Gurion was the embodiment of his nation’s complicated beginnings.

Born David Yosef Gruen in the Polish town of Plonsk in 1886, Ben-Gurion said he knew by the age of 3 that his home would be in the land of Israel. Hyperbolic as this sounds, his claim helps explain his lifelong mission to establish a Jewish state in Palestine. It also reflects the atmosphere in his home, where Ben-Gurion’s father was one of the town’s first Zionist activists. Even so, as a young man he felt directionless: He moved to Warsaw, was rejected by a technological college there, and eventually became so despondent that he wrote a friend, “I can’t find any interest in living anymore.”

Ben-Gurion found himself after arriving in Palestine in 1906 at the age of 20. He would later recall this period with pride, despite having realized fairly quickly that he was not cut out for the field work he was doing on a farm. Politics soon became his métier and the road to fulfilling his Zionist aspirations.

To prepare himself, Ben-Gurion traveled to Turkey to study law along with his friend Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, who later became Israel’s second president. After their studies were cut short by World War I, they eventually headed to New York City, where Ben-Gurion met and married Pauline (Paula) Moonweis. Their union was not without its problems — Ben-Gurion had several lengthy affairs and was a distant father to their three children — but the two remained together for 50 years.

By the late 1930s, Ben-Gurion and his socialist labor party had gained power not only in Palestine, but over the worldwide Zionist movement as well. Their goal was to establish a state with a Jewish majority in the biblical land of Israel. But in 1937, when the British Peel Commission recommended dividing Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, Ben-Gurion responded with “burning enthusiasm,” despite the tiny area allotted to the Jews. As he told colleagues, the fact of having a state was more important than its borders; besides, “borders are not forever.” The Peel plan fell through, but 10 years later Ben-Gurion accepted the partition resolution from the United Nations.

Although he made attempts at peace with the Palestinian Arabs, Ben-Gurion was pessimistic about ever achieving it. Long before the state existed, he met with a respected Muslim jurist, Musa al-Alami, whom he assured that the Zionists had come to develop Palestine for all its inhabitants. Alami said he preferred to leave the land poor and desolate for another century until the Arabs could develop it themselves. Ben-Gurion repeated this story again and again as proof of the futility of seeking agreement. At most, Segev writes, Ben-Gurion believed the conflict “could be managed,” not resolved.

Segev is best when probing the human side of the complex leader. Often brusque in manner, outwardly self-assured and iron-willed, Ben-Gurion poured his innermost emotions into his diaries and letters. “I am a solitary and lonely man,” he wrote to Paula. “There are moments in which my heart is boiling and torn, and bitter and difficult questions plague me.” He was periodically ill and bedridden, frequently unable to sleep. As Segev’s title suggests, the price of creating the state was steep — taking a personal toll on Ben-Gurion while costing thousands of people their lives and homes.

Where “A State at Any Cost” falls short is when the author injects his own ideology into the events of Ben-Gurion’s life. Segev has been associated with revisionist historians, known in the past as “new historians,” who challenge Israel’s founding narratives — sometimes with bracing reality, often with controversial positions disputed by other experts.

For example: Ben-Gurion and comrades who arrived in Palestine in the early 1900s embraced the idea of “Hebrew labor.” The term is widely understood to refer to manual work by Jews, rejecting centuries of work Jews did in the Diaspora as merchants and shopkeepers. The idea was to create “new Jews” who would cultivate the soil with their own hands. However, Segev defines the term differently. In his book, “Hebrew labor” is regarded not as a pioneer ideal, but as a means for Jews to displace Arab workers and control the labor market. He also makes a questionable connection between “Hebrew labor” and the flight of Arabs from their villages during the 1948 war, as though there were a planned and systematic scheme to push out the Arabs. In reality, the exodus of the Arabs from the designated Jewish state — the origin of the Palestinian refugee problem — is in itself a hotly debated subject. Scholars disagree about how many villagers left of their own accord and how many were expelled by Israeli commanders. There is no evidence that Ben-Gurion gave a central order to evacuate them all. He seemed surprised at first by the emptying villages, only later regarding the Arab flight as a boon to the military.

In 1963, David Ben-Gurion retired as prime minister. He spent most of the next decade in Sde Boker, a settlement in the Negev Desert. There, in the study of his two-bedroom house surrounded by almost a thousand books, he devoted much of the rest of his life to writing his memoirs. Through the drama of his life, and despite his failings — both personal and political — Ben-Gurion emerges in Segev’s book as a man of vision and integrity. These are qualities that Israelis, like the rest of us, long for in today’s leaders.

Francine Klagsbrun