A unique find on Mount Zion confirms the biblical history of Jerusalem

The tiny piece found in the 2019 excavation season, whose discovery was announced Saturday night, lends credence to biblical descriptions of Jerusalem’s riches before its obliteration by an infuriated King Nebuchadnezzar in the year 586 B.C.E.

The international team, led by the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, also found more evidence of the conflagration in the form of ash layers on Mount Zion itself, adding to evidence previous reports that a destruction layer from the Babylonians had been found below Temple Mount. They also unearthed what seems to have been a significant structure from the Iron Age – the first time major architecture from that time has been found on the “western hill,” aka Mount Zion. That building, which lies beneath archaeological layers from later periods, has yet to be excavated, the team tells Haaretz, but they hope to do that next year.

Meanwhile, the discoveries now reported by the Mount Zion Archaeological Project bolster the hypothesis that Iron Age Jerusalem had been a sprawling city, not some hilltop village, suggest UNC Charlotte professors Shimon Gibson and James Tabor and Dr. Rafi Lewis, a senior lecturer at Ashkelon Academic College and a fellow at Haifa University.

The ash layers were dated to the Babylonian conquest with the help of pottery fragments, such as oil lamps typical of the period, and also Scythian arrowheads made of copper alloy and iron, a type found at other archaeological battle sites from the seventh and sixth centuries B.C.E.

“For archaeologists, an ashen layer can mean a number of different things,” Gibson said. “It could be ashy deposits removed from ovens; or it could be localized burning of garbage. However, in this case, the combination of an ashy layer full of artifacts, mixed with arrowheads, and a very special ornament indicates some kind of devastation and destruction. Nobody abandons golden jewelry and nobody has arrowheads in their domestic refuse.”

Violently torn apart

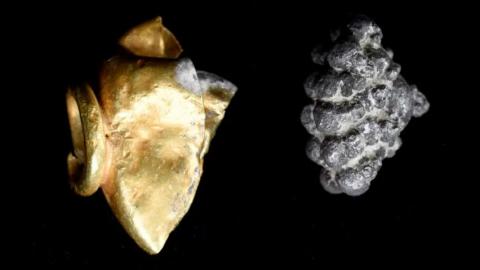

The jewelry consists of a bell-shaped gold part clasping a bunch of silver grapes. Too little remains to definitely say what it’s from: perhaps an earring or tassel, say the finders. The item seems to convey the brutality from millennia ago. “It went through trauma itself, was smashed somehow,” Lewis told Haaretz. “The little silver cluster of grapes is almost detached from its golden case, as if the jewel had been violently torn from somebody. You can almost sense the violence on the artifact itself.”

In the third year of the reign of Jehoiakim king of Judah came Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon unto Jerusalem, and besieged it. And the Lord gave Jehoiakim king of Judah into his hand, with part of the vessels of the house of God: which he carried into the land of Shinar to the house of his god. (Daniel 1:1-2).

This is first time an artifact resembling anything like this has been found in the clear archaeological context of the Babylonian destruction of the city, Lewis says: “No evidence of this kind of richness of material culture has ever been found inside the walls of Jerusalem before.”

Even if we don’t know what bigger object the gold and silver piece is from, it does support the biblical descriptions of Iron Age Jerusalem having been a place of riches. “The biblical books of Kings and Daniel dwell on the wealth of Jerusalem that Nebuchadnezzar took back to Babylon, and describe feasting using the gold vessels and copper vessels which came from the city,” Lewis points out. “This small artifact that shows the potential of how rich Jerusalem really was.”

Precious items have been found in the past, including in the City of David site last year, and Prof. Gabriel Barkay’s 1979 discoveries inside an Iron Age burial cave at Ketef Hinnom (above the Valley of Hinnom, which surrounds Jerusalem’s Old City), where the tiny Birkat Kohanim (Priestly Blessing) scrolls were found along with earrings. “Those seem similar to what we found, but Hinnom was outside the city at the time,” Lewis explains.

The archaeologists are not suggesting that the gold-and-silver earring or tassel was connected with the temple itself. “But it definitely belonged to somebody aristocratic,” Lewis sums up. “It’s not something a peasant would have lost or left behind.” Further suggesting that it was an inanimate victim of the Babylonian vengeance, he agrees with Gibson that nobody in his right mind would simply toss out a precious artifact like that.

Nebuchadnezzar ascendant

Around 2,600 years ago, the vassal king of Judah, Zedekiah, allied with the pharaoh of Egypt to throw off the shackles of Babylonian rule. Their revolt did not go well. Judah was attacked and after a long, onerous siege, Jerusalem was razed in 586 (or 587) B.C.E. for the first time in recorded history, if not the last. The Romans would repeat the act in 70 C.E., also to punish the city’s residents for their refusal to accept their hegemony and diktats.

Evidence of the Roman ire is legion, so to speak. Signs of the Babylonian destruction were more challenging to find, yet in 2017, archaeologists reported achieving exactly that: discovering signs of the conflagration inside stone buildings at the southern foot of Temple Mount, at the City of David site.

The two main archaeological schools regarding Jerusalem – “minimalists” who want hard evidence versus “maximalists” who seek proof of biblical veracity – have long argued about the size of the city during the late Iron Age. No Iron Age remains had been found in the western hills of Jerusalem before.

Now the newly found Iron Age edifice supports the view that Jerusalem had grown westward in the eight century B.C.E., swollen with refugees from the northern Kingdom of Israel, Lewis says. The building is in line with a fortification wall found in the 1970s in the Old City’s Jewish Quarter, which had evidently been built in preparation for assault by the Assyrians in 701 B.C.E. And the ash suggests that somewhat later, Babylonian battle spread down the hill too.

“We know that this is not some dumping area, but the south-western neighborhood of the Iron Age city,” said Gibson. During the eight century B.C.E. the urban area of Jerusalem grew from what is now called the City of David to the southeast, at least as far as the site of excavation.

The bottom line is it’s no surprise to find Iron Age building on Mount Zion, yet the fact is, it hadn’t been found before. It seems this area was important not only during the Second Temple period, but in the First Temple period, too.

“Our discovery is another nail in the minimalists’ coffin,” Lewis jokes. “Usually archaeologists deal with periods. Here we captured a moment in time, an event in an exact year, with everything that comes with destruction – ash, complete vessels, Scythian arrows” – and that jewelry fragment, silently suggesting extreme violence.

The Scythian-type arrowheads, which were common in the region in the sixth and seventh centuries B.C.E., were also used by the Babylonians. Gibson adds that the oil lamps found in the Mount Zion dig are typical high-based pinched lamps of the period.

“It’s the kind of jumble that you would expect to find in a ruined household following a raid or battle,” Gibson said. “Household objects, lamps, broken bits from pottery which had been overturned and shattered… and arrowheads and a piece of jewelry which might have been lost and buried in the destruction.”

King Zedekiah himself was captured and taken to Babylon together with the wealth of Jerusalem and its temple, the destruction of which Jews have been mourning ever since. Tradition holds that the temple was destroyed first by the Babylonians and later by the Romans, on the ninth day of the month of Av. How actually these two calamitous events in Jewish history – and some others too – came to be associated with the specific date of Tisha B’Av has been lost in time.

But as Jewish history expert Elon Gilad explains it, what’s certain is that sometime in the summer of 587 B.C.E., Babylonian forces besieged Jerusalem, and after much privation among the city dwellers, the enemy eventually breached the great stone walls, plundered the First Temple, and set it ablaze. The Jews were taken into captivity in Babylon where famously, “we wept, when we remembered Zion” (Psalm 137:1). And now we know the blaze spread beyond as well, to the greater city of ancient Jerusalem.

So the city was besieged unto the eleventh year of king Zedekiah. On the ninth day of the [fourth] month the famine was sore in the city, so that there was no bread for the people of the land. Then a breach was made in the city, and all the men of war [fled] by night by the way of the gate between the two walls ... And he [Nebuzaradan, the Babylonian captain of the guard] burnt the house of the Lord, and the King’s house; and all the houses of Jerusalem, even every great man’s house, burnt he with fire.

(2 Kings 25:1-9).

The Mount Zion archaeological project is sponsored by Aron Levy, John Hoffmann, Cherylee and Ron Vanderham, Patty and David Tyler and others, and facilitated by Sheila Bishop for the Foundation for Biblical Archaeology. The Mount Zion project is within the Sovev Homot Park and is administered by the Israel Nature and Parks Authority.

Ruth Schuster