Ig Nobel awards 2017

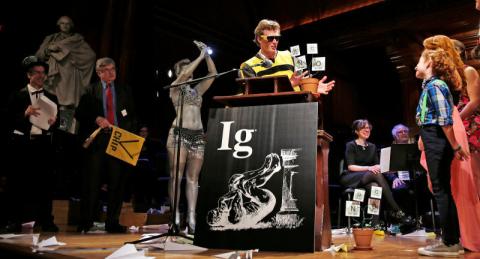

The theoretical treatise, entitled On the Rheology of Cats, argues that cats can technically be regarded as simultaneously solid and liquid due to their uncanny ability to adopt the shape of their container. The annual awards ceremony for research that “first makes you laugh, then makes you think” took place at Harvard University on Thursday evening, with three bona fide Nobel laureates, including the British-born economist Oliver Hart, on hand to distribute prizes.

The 10 awards included the peace prize, given to a Swiss team for their discovery that taking up the didgeridoo reduces snoring and the economics prize, which went to an investigation into how contact with a live crocodile affects a person’s willingness to gamble. James Heathcote, a GP from Kent, received the anatomy prize for solving the long-standing mystery of why old men have such big ears (they don’t keep growing, gravity stretches them).

Marc-Antoine Fardin, of the Université Paris Diderot and sole author of the cat paper, was inspired by an internet thread featuring absurd photos of cat-filled containers, ranging from sweet jars to sinks. “This actually raised some interesting questions about what it means to be a fluid and so I thought it could be used to highlight actually serious topics at the centre of the field of rheology, the study of flows,” he said.

Fardin’s subsequent paper, published in the Rheology Bulletin in 2014, explores how to calculate a cat’s “Deborah number”, a special term used to describe fluidity, and speculated on how cats might behave if subjected to the “tilted jar experiment”. “If you take a timelapse of a glacier on several years you will unmistakably see it flow down the mountain,” he said. “For cats, the same principle holds. If you are observing a cat on a time larger than its relaxation time, it will be soft and adapt to its container, like a liquid would.”

The ceremony also recognised a Swiss team for showing, in a randomised controlled trial, that didgeridoo playing reduces snoring and eases the symptoms of obstructive sleep apnoea. This could be due to the improving effect on tongue muscles and the reduction of “fat pads” in the throat. Some – the patient’s spouse, for instance – might question whether the treatment would simply replace one noise nuisance with another that could prove equally burdensome. But the approach seems to be gaining traction: since the paper’s publication, one of its authors has switched career to work full-time as a therapeutic didgeridoo instructor and has already taught around 2,500 patients.

Milo Puhan, a professor of public health and epidemiology at the University of Zurich and first author of the work, argues that the didgeridoo is “not worse than any other instrument”. Puhan said he was honoured to be a recipient, noting that some past Ig Nobel winners have subsequently upgraded to Nobel laureate status. “The president of my university was very excited about it,” he added.

Other recipients include the French neuroscientists who were the first to identify the brain circuits that underpin a hatred for cheese. The brain imaging study, in which people were asked to smell cheddar, goats’ cheese and gruyère while lying in an MRI scanner, pinpointed a region called the basal ganglia as the neural epicentre of cheese disgust.

The Harvard ceremony will also reward the observation by Italian scientists that many identical twins cannot tell themselves apart in pictures and the discovery of a female penis and male vagina in a Brazilian cave insect. Marc Abrahams, editor of the magazine Annals of Improbable Research and founder of the awards, said: “If you didn’t win an Ig Nobel prize tonight – and especially if you did – better luck next year.”

Hannah Devlin