Why do they leave Israel?

About 17 percent of the children of Russian parents who immigrated to the Holy Land in the early and mid-1990s have since emigrated, either to other Western countries or their native land, according to the data, which was requested by Haaretz. Although there is no official information about the education levels of immigrants who leave the country, a study conducted about a decade ago by Eric Gould and Omer Moav at the Hebrew University found that the brain drain among former Russian immigrants was particularly high. “The emigrants have a relatively clear profile: most are young and educated,” says Dr. Michael Philippov, from Jerusalem’s Myers-JDC Brookdale Institute. He has done years of research on the 1990s wave of Russian aliyah.

“This is a major national problem,” says Prof. Larissa Remennick, a Bar-Ilan University sociologist who is researching “Generation 1.5” – those who fall between the immigrant generation and the native-born one. “Israel is not making sufficient efforts to retain these talented and educated young adults who were brought here with such a major investment,” she says. “Israel has been making huge efforts in arranging aliyah – in looking for Jews, half- and quarter-Jews in every corner of a huge Russia,” she continues. “They bring them to programs such as Na’aleh and Sela and Birthright, and whatnot, just so they come. But when they do come, they allow them to fend for themselves as they try to keep their heads above water. That’s particularly true regarding the large [Russian] aliyah of the early 1990s.”

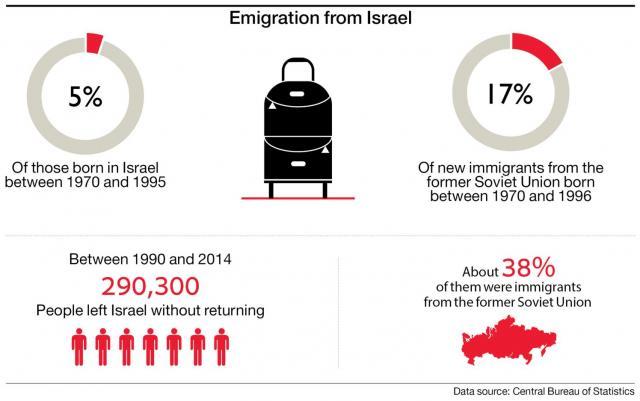

CBS figures show that between 1990 and 1996, some 650,000 immigrants moved to Israel from the former Soviet Union. About 185,000 of them were less than 20 years old. But the data reveal that some 32,000 of them (17.3 percent) no longer live in Israel. For purposes of comparison, the emigration rate is between 11 and 13 percent among all immigrants from the former Soviet Union. Among native Israelis born between 1970 and 1995, the emigration rate is much lower – about 5 percent.

However, Hebrew University’s Prof. Sergio DellaPergola – who studies Jewish migration – counseled caution over the numbers. “The expectation that everyone will come and not a single person will leave is baseless,” he says. “Jews are immigrants, like everyone else. Of course the added value of the ideological and religious direction is very important. But we are dealing with human beings who need to work and earn a living, to adjust and be happy.” DellaPergola and Remennick agree that the emigration of young, educated people is, among other things, a by-product of the good education they receive in Israel, along with the country’s relatively limited job market.

Prof. Yossi Harpaz, from the sociology and anthropology department at Tel Aviv University, who also studies migration, says the emigration of young educated people is typical of relatively wealthy countries. “People with higher human capital are inclined to look for opportunities in larger, wealthier countries,” says Harpaz. “That’s in contrast to emigration from countries such as Turkey and Mexico, where it is actually the poorer and less well-connected people who seek to leave.” Harpaz may be referring to people like Ilana Dvorkin, a management engineer who moved from Be'er Sheva to Montreal nine years ago. "I was in the last year at university and my husband had just started a career service," she recalls. "We decided we had nothing to lose, and that if we wanted to make a change, we had to do it then." Their decision was also based on fear, she says, following a spate of terror attacks in Israel.

Philippov, meanwhile, suggests looking at emigration data with a more critical eye. “Anyone who was satisfied that there were fewer emigrants this year than the year before should ask what will happen if one year all of those who want to leave do so. The year after that, we would report no emigration. Would we be happy with that?”

DellaPergola suggests that among those who are not Jewish according to religious law (i.e., they were not born to a Jewish mother), the emigration rate is particularly high. He points a finger at the Israeli Chief Rabbinate, which is responsible for conversion of residents in the country. He called the Rabbinate’s conversion policy “selective and lazy, and not in keeping with the supply.”

But the percentage of non-Jews among those who immigrated from the former Soviet Union in the early ’90s is a relatively low 11.2 percent, so it’s hard to believe the lack of recognition of Jewish identity is a major reason these immigrants leave as adults.

However, it was a factor for Daniel Tkatch, who came to Israel from Kazakhstan in 1992, at age 13. He could have been a successful engineer, but emigrated to Germany immediately after receiving his degree in materials engineering from the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa. “I was integrated according to all the formal parameters, but I’m not a Jew and was always reminded of that,” he says. “It caused a type of schizophrenic split within me. It follows me to this day: this feeling that I’m not what I really am, and this unending search for what’s wrong with me. It’s something internal that interferes with your life, and with accepting your whole self.” Tkatch says he hadn’t clearly formulated his reasons for leaving when he departed. “I just ran,” he says. “I fled the lack of a future.” In retrospect, he understands one of the things that pushed him to leave was the Zionist ideology, plus his inability to reconcile the concepts of “Jewish” and “democratic.”

Sophie (not her real name), 37, left Israel two years ago with her husband and two daughters, after being accepted to a postdoctoral program in New York. She doesn’t plan to return to Israel, to which she came from Ukraine, in 1990 with her parents. She lived a typical Israeli life – army service, followed by university, a job and then marriage. Before leaving for New York, she lived with her family in the Tel Aviv suburb of Givatayim. She does not intend to pursue an academic career after her postdoctoral work. “We wanted to try living in New York, and if we liked it we would stay,” she says. “The postdoctorate is necessary to continue in academia, but it’s also a good means of living legally in the United States for a time.”

Sophie and her family didn’t have a bad life in Israel. Her husband, a high-tech programmer, earned a good living, while she had received a generous scholarship and studied life sciences. But the opportunities for future development were limited. The couple felt they had reached their maximum income potential, but still couldn’t afford to buy an apartment in the places where they wanted to live. Sophie adds that the security issue in Israel had started to stress her out. Referring to the 2014 war with Hamas in Gaza, Sophie notes: “When rockets fell on Tel Aviv [none actually hit Tel Aviv, because they were intercepted by the Iron Dome defense system], it was already too much – especially when there are little children sleeping and it’s not clear what to do.” Sophie says there are major disparities among schools for her children in the United States, but it was possible to choose between them. In Israel, she says, the choice was more limited and the level of education did not meet her standards. She also hesitantly admits that in Israel she was bothered that her daughters spoke to her in Hebrew (rather than Russian), but now she is less bothered by their speaking English.

In addition to Israel, sizeable number of Jews leaving the former Soviet Union in the ’90s went to the United States, Canada and Germany. There are no official figures that would allow for comparing the rate of emigration from those countries. However, Remennick says that, based on expert assessments and personal meetings abroad, she believes the inclination of talented and educated former Soviet Jews to leave those countries is lower than their counterparts in Israel. “That’s not surprising,” she says, “because we have a small country with a small job market and very limited opportunities.” But Remennick believes emigration also enriches Israel. “In the fields of science and the arts, it doesn’t necessarily matter where a person lives. Anyone who lives here at least 10 years is infected by the Israeli ‘virus’ and isn’t able to cut his ties to the country completely.”

A study conducted by the Israel Democracy Institute in 2009 (with Philippov’s participation) showed that half of young people who had originated in the former Soviet Union unequivocally linked their future to Israel, compared to 80 percent of young, native-born Israelis, and that less than 30 percent of the young Russian speakers wanted to raise their children in Israel. A study commissioned by the Russian-language Israeli website Newsru, published last week, showed more moderate numbers, with 66 percent saying they weren’t planning to leave Israel, and only 4 percent to 5 percent weighing a move abroad. Philippov says there are two types of factors pushing Russian-born young adults to emigrate; some are common to all young adults in Israel, while others are unique to them. “The Israeli middle class is suffering from the cost of living,” he notes. “The situation becomes a lot more complex when a young family isn’t supported at all by their parents, or in cases in which the parents need their children’s help. That’s the typical reality of immigrant families and is less typical of ‘sabra’ families.”

The lack of separation between religion and state is also an issue troubling large parts of Israeli society, but the lack of civil marriage can be a serious problem for immigrants – who are more likely to face obstacles to marrying in Israel. Additionally, “A migrant may feel fewer sentiments toward a country in which he wasn’t born or raised,” says Philippov. “He has fewer family ties encouraging him to stay.” After leaving Israel, Tkatch has become a German citizen and renounced his Israeli citizenship. He says giving up his Israeli passport was a liberating move, but immediately after getting German citizenship, he moved to Brussels. “Again I was an immigrant,” he says.

Sophie, meanwhile, says it wasn’t until she was living in New York that she recognized what bothered her about Israel. “When I got here, I saw that everything was much calmer and more polite. People know how to line up for the bus without pushing, they don’t talk on their cellphone on public transportation – and if they do, they lower their voices. Everyone is polite in the stores, and it’s customary to hold the door open for one another. That’s something I still have to learn; I’m not used to it.”

Philippov notes it is in Israel’s interest to ascertain how many of its best and brightest young people have been lost in recent years. “Why did we lose them? This is an important question from a socioeconomic perspective,” he says.

Liza Rozovsky