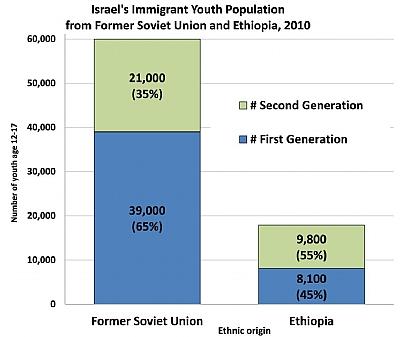

Second generation Ethiopian and Russian Immigrant Youth

Immigrants from the Former Soviet Union (FSU)

The survey found very significant improvements between the first and second generations of FSU youth, with the second generation becoming very similar to non-immigrant Jewish-Israelis. For example, first-generation immigrant youth from the FSU stand out from all other immigrant groups in terms of higher proportions of risk behavior and weaker identification with Israel.

In the second generation, however, risk behaviors such as rates of smoking, experiences of drunkenness, and truancy from school declined considerably, and brought this cohort in-line with non-immigrant Jewish-Israelis.

As for identity, the proportion of FSU youth who strongly felt at home in Israel rose to levels quite similar to non-immigrant Jewish-Israelis. More striking, 68 percent of second-generation FSU youth identified themselves solely as “Israelis” without any reference to their FSU origins (more than double the 33 percent among first-generation youth).

Immigrants from Ethiopia

The experiences of second-generation Ethiopian-Israelis tell a different story, one where many challenges persist or even worsen in the second generation. Risk behavior increased dramatically between the first and second generations of Ethiopian-Israeli youth. Rates of smoking and drunkenness more than doubled between the generations (from 11 percent to 23 percent for smoking, and from 11 percent to 25 percent for being drunk at least twice).

School truancy increased, as did the percentage of students failing more than 3 classes. Fewer second-generation Ethiopian-Israelis felt that they had someone to turn to in school if there was a problem, indicating higher levels of alienation from school. By contrast, the percentage of students passing their high school completion/matriculation exams at a level required for entrance into higher education does improve in the second generation.

Ethiopians in the first and second generations have strong Israeli identities. This identification to Israel has not come at the expense of a continued strong Ethiopian identity. More than 70 percent of second-generation youth identify themselves as Israeli and Ethiopian (versus 11 percent who identify as “Israeli” alone). They also have a particularly strong Jewish identity.

The Complex Process of Immigrant Integration

The different trends we have found between FSU and Ethiopian youth have parallels in the international literature on immigration, which shows that stronger immigrant groups typically show improvements in the second generation, whereas weaker immigrants typically or quite often show declines in the second generation. It is also not easy to generalize about the expected experiences of immigrant youth, because of the wide range of backgrounds.

What is needed is a long-term perspective when considering immigrant integration in Israel. Although most government benefits to first-generation Ethiopians have been extended indefinitely, the second-generation Ethiopian-Israelis are ineligible for such benefits. The survey also found that families from the FSU and non-immigrant Jewish-Israeli families extensively supplement the public educational assistance with the purchase of private tutoring, while the lower incomes of most Ethiopian-Israeli families makes such private tutoring barely possible. It is crucial, therefore, to maintain strong service and cultural supports for these immigrant groups whose integration is taking longer for a variety of social and economic reasons.

In response to the survey findings, Sara Hacohen of the Ministry of Immigrant Absorption, who coordinated the interministerial steering committee that accompanied the study, noted the importance of differentiating between different groups of immigrants. “We are happy to see the successful integration of the large number of second-generation immigrants from the FSU. Given our limited resources, this understanding enables us to focus more on those who are not doing as well and who particularly need our help, such as the Ethiopian immigrants.”

Immigration to Israel is a story that continues to unfold. MJB looks forward to continuing to contribute to Israel's efforts in addressing the needs of its immigrants.