The tragedy of the Aleppo Codex

For me, there is nothing more alive than a book. And for many, there is no book more alive than the Bible. Humanity has bowed down to it for thousands of years, lived by it, killed and been killed in its name. Our relationship with the Bible has been a passionate – and frightening – love affair made of true devotion (to God), raw emotion, honor, and the uncontrollable lust for control.

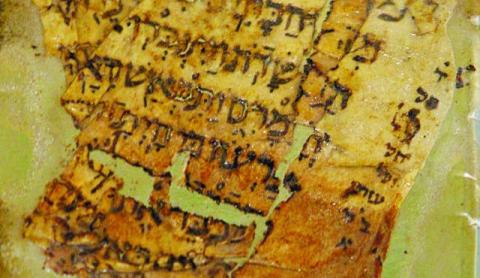

The story of the Aleppo Codex, the oldest extant manuscript of the Bible, epitomizes this relationship. Since it was written in 930 C.E. in Tiberias, the Codex has been considered the most accurate copy of the Hebrew Bible and described by those it has inspired as the most faithful version of the Word of God.

Among the latest to fall under its spell is journalist Matti Friedman, whose imagination was ignited by a chance meeting with the text at the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem where the incomplete manuscript is located. When he learned that the object of his affection had been recently robbed and hurt – hundreds of pages disappeared during the Codex’s journey to Jerusalem in the middle of the last century – Friedman sought to bring the perpetrators to justice.

His new book, “The Aleppo Codex: A True Story of Obsession, Faith, and the Pursuit of an Ancient Bible,” recounts the history of the beloved text and investigates the Codex’s unfortunate modern fate, identifying those he believes are responsible. Friedman writes that even if the Aleppo Codex will never be whole, he felt obligated to complete its life story. That, he says, is our duty to the people who wrote the Codex and guarded it with their lives for a millennium. Friedman succeeds not only in solving the mystery from mere scattered hints and fragments of information, but also breathing new life into the story of the Codex.

A unified text for a dispersed people

The name Aleppo Codex was given to the manuscript in Tiberias by the scribe Shlomo ben Buya’a and the grammarian Aaron ben Moses ben Asher, a legendary transcriber of Hebrew text. Because of Ben Asher’s authority, the Codex was considered from the beginning to be the most precise version of the Bible. Future scribes and grammarians would copy it in their own handwriting and proofread their own copies against it.

This precision and uniformity of the duplicates was important because of the central role of Torah in Judaism: With the exile that followed the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E., the Torah served as a unifier to connect and preserve the scattered Jews.

To ensure this unity, each version of the text must be identical, including vague and confusing sections and symbols. So hundreds of years after the Temple’s destruction, groups of sages in Tiberias began to edit the Bible. The purpose of the project, which lasted centuries, was to assemble and document oral traditions, reach consensus where there had been disagreement, and ultimately create the text upon which all subsequent copies of the Bible everywhere in the world would be based. It was Ben Asher who completed this enormous project, using the Aleppo Codex.

While there are tens of thousands of Torah scrolls in the world, Friedman points out, there is only one Aleppo Codex. A thousand years later, biblical researchers still see it as the most important book in existence.

The Codex escapes to Israel

The Codex, like the Jewish nation it was meant to preserve and lead, endured many hardships. It continuously wandered, hid, fled and was miraculously rescued from pogroms. At the beginning of the 11th century, it was brought from Tiberias to the Karaite community in Jerusalem. In 1099, it was stolen by the Crusaders, who put it up for sale. This news reached the wealthy community of Fostat, near Cairo, who raised an enormous sum to buy it back. The great Talmudic scholar Maimonides relied on the Codex, now in exile in Egypt, when he wrote his significant work of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah.

Around the 14th century, a fifth-generation descendant of Maimonides immigrated to Aleppo, now in modern day Syria, taking the Codex with him. There, the Codex received its contemporary name and became the jewel of the city’s Jewish community, preserved for centuries in an iron chest in a crypt in the city’s synagogue. A legend developed that on the day it left the city limits, the community would be destroyed.

When the War of Independence broke out in 1948, anti-Jewish rioting began in Aleppo. The synagogue was desecrated, looted and partially burned. The synagogue’s beadle, Asher Baghdadi, found the Codex on the floor of the synagogue, some of its pages scattered. He gathered them and gave the Codex to the rabbis. Together, they hid the Codex in various secret locations, spreading a rumor that it had been lost in the flames. Ten years later, in 1958, with help from the State of Israel, including President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, it was smuggled to Turkey and received by an emissary of the Jewish Agency. From there the Codex was brought to Jerusalem, where it remains today, and presented to Ben-Zvi.

Shortly after its triumphant return, it was discovered that nearly a third of Codex was missing. The approximately 200 lost pages comprised the Five Books of Moses – the Torah itself. The Codex’s dramatic journey and the mystery of its condition inspired Amnon Shamosh’s wonderful novel “Michel Ezra Safra and Sons” and other books. It is also from this point that Friedman began his research.

A happy ending too good to be true

Friedman’s sharp journalistic sense told him there was something odd about the Codex’s neatly tied-up story – and he was right. In detailing the fate of those missing pages, Friedman lays bare a disturbing parallel story of European Zionist snobbery toward Jews from Arab countries that enabled the looting of the Codex, its concealment and its appropriation by an exclusive research institute, headed by President Ben-Zvi.

The Aleppo Codex is not the only case of such plundering. When the Jews of Yemen came to Israel, writes Friedman, they left all their property behind but brought their books, mostly manuscripts and Torah scrolls, many of them ancient. Friedman explains that Ben-Zvi’s associates had a large appetite for ancient Hebrew books from the east, including those of Yemenite Jews. When the latter group immigrated, they were told to deposit their books with the staff of transit camps. Many of them never saw their books again.

Ben-Zvi later said that when he visited the Aden transit camp in 1959, he scanned books to see if there was anything of value for his institute. The Yemenite rabbis who asked for their books back found they had disappeared. One wrote an angry letter to the Jewish Agency, asking how the books had been safe in an Arab country, but stolen in the Land of Israel. Another says he was told that if he continued to pester anyone about his books, he would be forced to pay the cost of his immigration to Israel.

Friedman pays special attention to the proceedings of a trial in which the heads of Aleppo’s Jewish community brought a lawsuit against the State of Israel for stealing the Codex. The state was accused of abusing its power and bribing the emissary in Turkey. Ultimately, the state pressured the Aleppo community to sign a compromise agreement for joint ownership of the Codex, stipulating that it would be kept at the Ben-Zvi Institute and moved only with approval of the joint board of trustees. The stated reason was the welfare of the Codex.

Devoured by those it was meant to save

Here, Friedman comes to the most troubling section of his book. In his research, assisted by Rafi Sutton and Ezra Kassin among others, Friedman reaches the conclusion that the Codex was never saved from any flames, but rather was looted – not by rioters in Syria but in Israel by representatives of the Ben-Zvi Institute. Friedman points directly to the man he believes responsible – Meir Benayahu, the institute’s director who passed away in 2009.

Dr. Zvi Zameret, a director of Institute for 26 years, admits to Friedman that Benayahu was responsible for the disappearance of dozens of manuscripts from the Ben-Zvi Institute. Israel’s then-president Zalman Shazar intervened personally in the matter and therefore no investigation ever took place. Friedman cites additional testimony from those who kept mum on the matter, including high-ranking civil servants who aided the cover-up. Benayahu’s brother, former MK Moshe Nissim, asks why, in 40 years, no one took legal action.

Just as disturbing, Friedman reveals that the physical state of the Aleppo Codex has deteriorated in the Ben-Zvi archives. It was simply forgotten and neglected. A 1971 document by researchers with access to the Codex stated that, at that time, the Aleppo Codex was locked in an ordinary office cabinet, covered in fabric. Sections of the manuscript that had been legible only a few years before could no longer be read.

Internal accusations of negligence were traded back and forth for years, during which the Codex could have been transferred to the National Library for safekeeping in proper conditions. Ben-Zvi’s widow, Rahel Yanait Ben-Zvi, applied pressure to keep the Codex where it was because she felt it lent value and prestige to the institute. All the while, the institute refused to display the Codex to the general public or allow it to be photographed.

Friedman quotes biblical researcher Moshe David Cassuto who, more than a decade earlier, lamented the refusal of Aleppo’s rabbis to allow access to the Codex, pointing out that the Codex’s purpose was to be copied as much as possible. Yet once Ben-Zvi’s associates got what they wanted, they behaved in exactly the same way as the rabbis.

Friedman’s impressive search for the Aleppo Codex turns into, as he writes, “a tragedy of human weakness.” After surviving a thousand turbulent years, it was betrayed in our own time by our own people, those charged with guarding it. “It fell victim to the instincts it was created to temper,” he concludes, “and was devoured by the creatures it was meant to save.” For that, we should all be ashamed.

By Yuval Elbashan

Yuval Elbashan is the deputy director of YEDID: The Association for Community Empowerment. His book Tik Metzada (The Masada Case) was published by Yedioth Ahronoth Books.