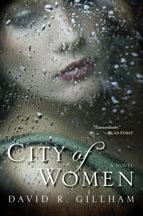

When Berlin was just a shadow of itself

But Sigrid’s life is also suffused with secrecy. She dreams of Egon, the married former lover -- and Jew -- whom she met at the local cinema and with whom she carried out a clandestine affair earlier in the war. She even assisted him with several secretive transactions as part of his underground efforts against the Nazis, but now he too seems to have vanished, like so many others in Berlin.

Sigrid and her fellow Berliners already face numerous constant challenges -- surviving frequent air raids, trying to be seen as toeing the party line, and subsisting on meager wartime rations, All in an atmosphere of deep paranoia and confusion. But now her life is about to become even more complicated.

On one of her regular solitary nights at the cinema -- the place where she goes to be alone and think of her former lover -- Sigrid is approached by Ericha, a young woman who is doing a year of national service working for one of her neighbors. She begs Sigrid to help her with a request that could save her life; Sigrid must tell the Nazi security police who have just entered the movie theater-- and are now searching the place -- that the two came in together.

This simple, if risky act is the catalyst for Sigrid’s life to transform into something entirely different, and also provides one of the central themes of the book, which is to push the reader to ask him or herself the moral question of what one would do in Sigrid’s situation, or in general when living in a totalitarian society. In an environment in which people struggle to survive, and one wrong move could be perceived as a betrayal of the Reich, it is easy to absolve oneself of responsibility. But Sigrid chooses to help the girl, who, as it turns out, is involved in an underground network that shelters Jews and other “undesirables” and smuggles them away from danger. In doing so, Sigrid becomes aware of the things she has not seen -- or has simply chosen to ignore -- up until that point.

As Sigrid becomes more deeply embroiled in Ericha’s work, she is also forced to deal with other developments, such as the reappearance of Egon, the return of her wounded husband from the Eastern front, and a new neighbor in the building-- a rather suspicious SS officer’s wife. Another, more unsettling development is also introduced, when Sigrid becomes convinced that the woman and her two young daughters she is helping to shelter are Egon’s wife and children.

Total war

Such an intricate storyline can easily descend into confusion, but first-time novelist Gillham succeeds in skillfully weaving these complex relationships together without losing focus. He also manages to create an elaborate yet believable depiction of the era, while ensuring that the impressive amount of historical detail and research that clearly went into the book paints an accurate picture of the time without overwhelming the narrative.

Though the story takes places against the backdrop of events with which its readers will doubtless be familiar thanks to the countless books, films and documentaries on the subject, the themes Gillham tackles are dealt with in a way that accords them due respect. We are told of the catastrophic defeat the German army suffered at Stalingrad in early 1943, and how “total war” has been declared. Informants betray their neighbors, people disappear in the middle of the night and buildings are destroyed in air raids. The claustrophobic feeling of Berlin in the early 1940s --a time when citizens pressed their ears to the wireless to hear illicit BBC broadcasts with the volume turned down to barely perceptible levels, or when failing to sing along to nationalist songs could have the Gestapo knocking at your door -- is powerfully conveyed.

Gillham studied screenwriting before moving into fiction, and his taut prose and dialogue reflect his training. In fact, it’s easy to imagine the novel as a film, with its shadowy characters stalking the city streets, its clandestine meetings and the pervading sense that no one can really be trusted. When a woman Sigrid is working with is captured, she wonders to herself: “Who knows what she might tell them? What she might have already told them?”

Gillham skillfully creates a compelling account of the era through the day-to-day interactions of the characters -- neighbors quarrel and coworkers gossip, as ordinary life is interspersed with the extraordinary. Sigrid sees a ruined piano that has been thrown out of a window lying on the street, its “harp split, pointing toward the sky, its strings popped. Keys scattered like broken teeth … An image of a crime, somehow more intimate, than the flat, black-and-white violence caught on film.”

The evocative writing style used throughout heightens the almost constant sense of fear, dread and desolation: A train passes Sigrid and “lit faces in the windows telegraph past, like creatures from a ghoulish dream.” This effective use of imagery also helps convey the ubiquity of death and devastation. The cinema Sigrid frequents regularly shows bombs onscreen “spewing whorls of dark earth” from the ground, the burning building on her street is “throwing off waves of heat,” and in conversation, facts are “tossed at Sigrid like a hand grenade.”

Berlin itself plays a prominent role in the story. It is depicted in the book as a shadowy metropolis with the majority of its men at war, a city that has been left to its women. Far from its vibrant heyday in the 1920s, this Berlin is a downtrodden city smelling of boiled cabbage, smothered with “an odor of human dank…. the smell of all that is unwashed, stale and solidified.” Passengers on commuter trains are “lumped together like potato sacks,” and as Sigrid walks down the street, the rain “has turned the pavement into a slick black mirror, throwing back a distorted reflection of the day.”

Though the backdrop to “City of Women” is one of the darkest periods of human existence, this historical novel also explores how war changes people, about the unfixed and unpredictable nature of our characters, and about how easily those boundaries are blurred. When Sigrid’s husband Kaspar is injured and returns to Berlin, scarred and ravaged from the traumas he has endured and inflicted, the formerly mild-mannered banker is now an entirely different person, recounting his own personal stories of the horrors of war. And at a certain point, Sigrid finds herself looking into a mirror that “holds the image of a stranger. Hair dangling. Eyes like stones.” As time passes, Sigrid, who has chosen to act in accordance with what she thinks is right, grows further away from her old self, as well as from the people around her, each day “separating her by one more unspoken word, one more degree of silence” from those she used to know so well.

As the book nears its climax, the slow-moving, absorbing pace the reader has grown accustomed to suddenly hurtles forwards in the breathless final chapters, which tie up several -- but not all -- loose ends. There is a sense that some issues are resolved a little too quickly, but this doesn’t detract from the rest of the story. Perhaps to counterbalance this, we are left not knowing exactly what will happen to Sigrid as she begins another journey, one that we wonder if she can complete. If the events that have led up to this point are anything to go by, then she is surely destined to fail, as it just seems to be too dangerous for her to continue placing herself at such great personal risk without being caught. But then again, Sigrid has hope, and has made the same choice she made at the start of the story: To help others at her own expense, and to do the “right thing” -- whatever that may be.

This sense of hope -- the feeling that the future still holds promise, and that good, in one way or another, will prevail -- is what the story is all about. True, Sigrid’s motivation isn’t always entirely clear, and some of her behavior, as when she cannily gets away with threatening a Gestapo officer who has followed her onto a train, can seem far-fetched. But maybe that’s not so important. For if it is indeed true that all that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing, then David Gillham’s heroine is not just a good woman but one who does her best to bring evil to its knees.

By Yasmin Kaye