Israeli schoolchildren - winners Intel ISEF 2015

But if casts were somehow adjustable, many of these problems — and their costs —could be avoided, the teens suggest. So, they came up with the idea for a balloon-like sleeve to line the inside of the cast and surround a broken limb. This air bladder can be inflated when a cast becomes loose, says Betty, to keep bones firmly in place. But when swelling becomes dangerously high, some air could be removed from the sleeve. A sensor inside the air bladder monitors the pressure inside the cast. Then a small computer keeps the pressure within the range that the doctor recommends.

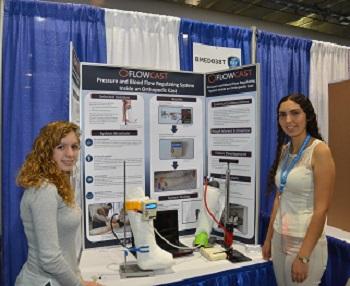

Betty and May provided details of their research at the 2015 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. This event was created by the Society for Science and the Public (which also publishes Science News for Students). The annual competition brought 1702 finalists here this year. They come from more than 70 different countries.

Betty and May built a prototype of their new system. It included the air bladder and the small programmable computer to control airflow into and out of the inflatable sleeve. The electronic equipment is lightweight and fits in a small box that can be easily mounted on the outside of the cast.

For now, the air bladder in their system has only one chamber. That means it’s like one big balloon, May explains. But future versions of the bladder might include several chambers, each with its own pressure sensor. That sort of design would be even more adjustable, says Betty. That might be useful when one part of a limb swells a lot but other regions don’t. A multi-chambered bladder also would let the teens include a “massage” function in their system. For short periods of time, the chambers could be inflated and deflated in sequence, pressing on the tissues and then releasing them.

With all of its benefits, the teens hope that their simple and largely reusable system will become a widespread part of treating broken bones.