When Jews lived the high life in an Egyptian paradise

Some critics have incorrectly labeled “Alexandrian Summer” as fictionalized autobiography. The novel is certainly self-referential in that the author, like Robby, grew up in Alexandria in a well-to-do family, which – also like Robby’s – fled Egypt in 1951 to transplant itself in Israel. But there is much more in this story that is the product of the author’s imagination.

Readers will be quickly drawn into a city the author describes in lush, voluptuous terms as a “paradise by the sea” where sensuality is pervasive. One could argue that Alexandria itself – and not a thinly disguised Goren, or Robby – is the essential character of this book. Though a boy of sweetly attractive innocence, Robby is simply not the most important figure in the story. The Sephardic Hamdi-Ali clan, including two sons and a daughter, is for the most part the focus of Goren’s rich invention. They, along with Robby’s parents, Salem, an Arab servant, and several gossipy neighbors provide the narrative and the meaning of “Alexandrian Summer.”

We meet the Hamdi-Ali family in 1951 as new summer tenants in Robby’s parents’ spacious house, walking distance from the beach. Joseph Hamdi-Ali, handsome and patriarchal, is a respected famous former jockey. His name and Turkish background, however, are a matter of both wonder and doubt in the minds of other cosmopolitan Jewish vacationers from Cairo, who converse in French, Italian, Spanish, Greek, English and Ladino. Note the absence of Arabic. Joseph has never recovered from the death of his horse, which he appears to have loved even more than his wife. His thoroughbred gone, his career as a jockey collapsed, he now counts on his eldest son, David, a good-looking, obsessive and arrogant hotshot jockey, to fulfill his hopes. At the same time, Joseph ignores his 11-year-old-son Victor. Often humiliated and sometimes beaten by his distressingly impatient older brother, Victor, suffering and apparently “disturbed,” seduces Robby and his friends into potentially harmful homosexual activities, while several sets of absent parents are busy playing cards or betting on the ponies.

These Alexandria Jews are cosmopolitan, and while not entirely secular, they are more likely to be found gambling, café-hopping and touring, than attending to their children or in the synagogue, even on the Sabbath. Throughout, David lusts after and wants to marry Robby’s older sister who, though never named, is vividly depicted by Goren. She teases, hesitates and vacillates in her relationship with David and is reluctant to leave her beloved family “who gave her complete freedom.” But her use of the phrase “beloved family” seems inconsistent with her picture of marriage as “constant friction… always… the same man, morning, noon, and night.”

Goren stumbles a bit here because we never learn enough about the young woman’s mother and father to judge whether her depiction of matrimony comes from their relationship. None of the Jewish characters interact with the indigenous population except in employing Arabs as servants. Poorly paid and overworked, these employees privately resent the extraordinary gap in wealth between themselves and Jews.

Goren, who, variously narrates in first, second or third person, explains that Alexandria “lets you live like a carefree lord without even being rich.” Of course, you had to be Jewish or European and not want to be a “nobody.” And obviously you “can’t be a nobody if you have two servants… living and toiling in your home 24 hours a day, six-and-a-half days a week (on their half day off they go to their miserable villages to see their sick parents and their lice-infected siblings) – all for four Egyptian pounds.” That’s right, say two unnamed interlocutors: “They don’t deserve any more than that!” And, “They’re so lazy!”

Combustible situation

After Robby is presented with an outrageously expensive toy for his birthday, Salem, the family’s primary servant, calculates that the toy cost more than he would earn in seven months. “When the reality of these numbers sink in,” Salem’s “humiliation was overpowering… Would he ever be able to buy such a toy for his own son?” And then, understandably even more troubled, he thinks, “Would his son end up a servant just like him? His grandson?” It is through such scenes that Goren, with his characteristic light touch, makes us aware of the contemptuous treatment of Arabs, particularly Arab servants, in Jewish and European households.

We also see, despite what appears to be peace in Jewish-Muslim relations, a resentment and bitterness beneath the surface of a rapidly changing post-war Egypt. One of the more telling examples of how combustible things were in this multi-ethnic country involves Joseph Hamdi-Ali. He is accused of drugging the horse of a renowned and beloved Arab jockey, after the Muslim favorite loses a race to son David. Joseph, enraged either by the unjust charge or his own guilt in the matter, attacks his accuser.

From the crowd, with a stunning suddenness, come cries of “Maut al Yahudi! Death to the Jews!” Others shout, “Sahyuni! Sahyuni!” meaning “Zionist!” – the classic opening for anti-Jewish riots. The Arabs are ready to unleash deep rage against Westerners and British colonialists, too, but here at this moment Jews are the target. Robby’s sister, who had been at the track, tells him that “We were a little scared, but thank God, the voices were few, just a bunch of hotheaded young guys, maybe some students from the Muslim Brotherhood.”

Wishful thinking, no doubt, but the denial was only temporary: Robby’s father knew, even before the riot, that their family’s future was in Israel. Only months after the racetrack incident, and at the close of the novel, they leave Egypt. Prescient perhaps, because much worse was to come with the overthrow of King Farouk’s regime in 1952, and worse still with the Suez war in 1956.

Wrapped in nostalgia

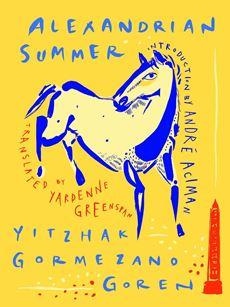

Anti-Semitic rhetoric and threats increased exponentially after both events. Jews whose ancestors had been in Egypt for over 1,000 years were rendered “stateless” – 40,000 foreigners in their own country – while legal discrimination, isolation and economic appropriations were widespread. On the subject of Jews leaving Egypt, English-language readers are probably most familiar with two admirable memoirs, Andre Aciman’s “Out of Egypt,” and Lucette Lagnado’s “The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit.” The Lagnado family did not leave Egypt until 1963; Aciman, who in this edition of “Alexandrian Summer” provides an introduction (historically flawed in some places, but valuable for his personal experience and point of view), remained in Egypt with his family until 1966. Both memoirs and Goren’s novel, too, though wrapped in layers of nostalgia, suggest a relatively strong Jewish attachment to Egypt, especially to Cairo and Alexandria.

We don’t learn if or when the Hamdi-Alis emigrate. And that brings us back to Joseph. Early in the book, we learn things about him that most of his neighbors and guests never hear about. The patriarch’s real name is Yusef, and many years earlier he had secretly converted to Judaism to please the woman he was to marry. But he surrendered his commitment to Islam with fear and trembling. When his son David competes again against the “unbeatable” Muslim Jockey, Joseph experiences unbearable tension and anxiety over his own identity and loyalties. He is afraid Allah will punish him for his conversion to Judaism, and that David will be prevented from winning. Panic drives him toward dark and desperate deeds. Goren succeeds in making Joseph an embodiment of rising Arab-Jewish friction, and at the same time the personification of peaceful coexistence, if not unity between Muslim and Jew.

In this regard, it is worth mentioning “The Jewish Quarter,” a popular series on Egyptian TV that aired during Ramadan, which, though repeating some unfortunate anti-Semitic stereotypes, generally portrays Jews sympathetically. Depictions of Jewish families at prayer in a Cairo synagogue in 1948, for example, are respectful and sensitive; there is also a budding romance between a young Jewish woman and a Muslim military hero. The military’s real role under Gamal Abdel Nasser in forcing Jews out of Egypt is, of course, never mentioned.

In 1979, one year after Goren’s book was published in Hebrew, Egypt and Israel signed a peace treaty. But the dream of a stable polyglot society in Egypt itself, as depicted in “The Jewish Quarter,” was not realistic even well before 1947, when the chief Egyptian delegate to the United Nations bluntly told the General Assembly that “the lives of one million Jews in Muslim countries” would be “jeopardized” by the partition of Palestine.

Between 1948 and 1949, 20,000 of the 80,000 Jews in Egypt emigrated, most to the United States and Israel. Between 1950 and 1956, another 5,000 departed, including Goren’s family. They made good lives elsewhere, but as with the families of Lucette Lagnado and Andre Aciman, part of their hearts remained in Egypt.

Gerald Sorin

Gerald Sorin is distinguished professor of American and Jewish Studies at SUNY New Paltz.