Religious Public Schools Teach Children to 'Long for the Third Temple'

Since the beginning of the school year, it should be noted, Muslim claims that Israel is trying to change the status quo on the Mount, which is now the site of the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, have been the backdrop for a wave of Palestinian violence. Israel denies any effort to change the status quo, which grants only Muslims the right to pray at the site and other religions the right to visit at certain hours.

The curriculum follows years of Education Ministry support for a series of lectures and workshops by the Temple Institute for religious as well as secular students. Last year, the ministry provided some 330,000 shekels ($85,300) for the institute, which provides workshops and lectures for both religious and secular students.

The section dealing with “Love of the Land and the Temple” is part of the social studies curriculum in state religious schools. Development of the curriculum began about seven years ago, an Education Ministry source said, and since then has undergone a number of adjustments. This year, the curriculum – which is geared for grades 1 through 6 – is mandatory as part of the students’ study of faith. There is no direct reference in the set of lessons or elsewhere in the section on “Love of the Land and the Temple” to Al-Aqsa Mosque, which has been such a flashpoint in recent weeks.

More than a month ago, Berman Shifman – a doctoral student in the Department of Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem – wrote to the national elementary school supervisor after reading the lesson materials.

“As far as I know, the Torah commands us to love human beings and the Almighty. It appears that ‘Love of the Land and the Temple’ denies this when it exalts things our forefathers had not imagined and seeks to etch [them] in the consciousness,” he wrote. At press time, he had yet to receive a reply. In response to Haaretz’s query, the ministry said, “Love of the Land and the Temple” is just one section of a 12-part curriculum that students study over a three-year period. The program was written by social studies professionals from the Religious Education Administration, has been operating in elementary schools for seven years and deals with social topics and values.”

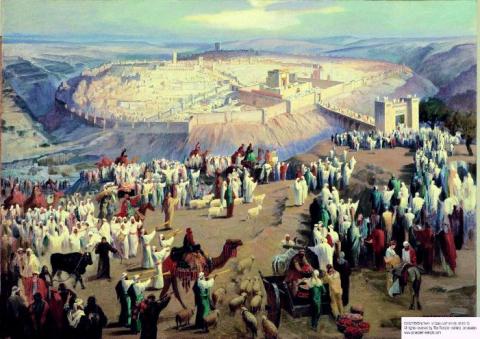

The beginning of the “Love of the Land and the Temple” curriculum states, “It is impossible to talk about the Land of Israel without speaking about the Temple. The Land of Israel and the Temple are attached to one another ... The Temple is at the pinnacle of the aspirations of the Jewish people and humanity as a whole.”

The website for the program includes supplementary educational materials, including “A Tisha B’Av fantasy” written several years ago by Nehemiah Kuperschmidt of the Orthodox educational organization Aish HaTorah. “I have a fantasy about getting together [former Iranian President] Ahmadinejad, [Hezbollah leader] Nasrallah, [Palestinian President] Abbas and [UN Secretary-General] Ban Ki-moon and taking them on a visit to the new Temple, the Third Temple now being built on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem,” the fantasy reads, “and letting them see the coronation ceremony from there of a new king of Israel. The Vatican is returning the ancient golden menorah and the high priest is rededicating it” – a reference to the claim that the Vatican is holding a golden menorah from the Second Temple, which was destroyed by the Romans in 70 C.E. Kuperschmidt later imagines “the heads of modern atheism” who, “for the first time in their lives, have the privilege of feeling the supreme power and divine majesty.”

This imagery has a purpose. “We have no Temple and we live in a world in which Israel is threatened from within and without, a world in which the Lord and his Torah are ridiculed,” Kuperschmidt writes, adding, “None of the conflicts from which the Jewish people are currently suffering – the existential threats, disagreements between religious and secular, rising assimilation, confusion and discord – would have bothered us if we had the Temple in our vicinity. When the Temple existed, there was no question as to who had the right to the Land of Israel and Jerusalem. No one cast doubt over the existence of the Lord.”

Longing for the Temple

To convey a sense of the loss of the Temple, the workshop proposes that teachers explore the following: “A list of the most major threats, both spiritual and material, facing the Jewish people, and add all your personal difficulties and those of your students. And then think about how each item on the list would be different if we had the Temple right here, right now.”

Kuperschmidt’s ideas are almost directly translated in the lesson dedicated to “Longing for the Temple,” and include “Bringing together the reality of the revelation of the Lord through miracles connected to the Temple.”

'Brainwashing, not education'

“I’m afraid that this heavy emphasis on a yearning for the Temple and concrete study of the work of the Temple could spur rather good students to think about other practical actions,” says Ariel Picard, a research fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. “It’s enough for one student to decide that it’s worth blowing up mosques to advance the building of the [Third] Temple. The Jewish Underground’s plan to blow up the Temple Mount mosques still exists in the collective memory of religious Zionism,” he says, referring to the Jewish militant group from the late 1970s and early 1980s whose leaders were jailed for their terrorist activities.

“When you tell students that the Temple menorah is not an abstract matter, or say we need to deal with Jewish law related to the red heifer [used in ancient Temple animal sacrifices], that’s a stage that lays the ground for passion for the Temple. We don’t need to explicitly say we need to ‘cast out abomination’ on the Temple Mount, but the Religious Education Administration, whether consciously or not, is trying to create a view among students that we are on the verge of redemption.”

Aviezer Weiss is a former principal of the religious Zeitlin High School in Tel Aviv and ex-head of the Givat Washington Academic College of Education, Upper Galilee, who defines himself as politically right-wing. His criticism of the “Love of the Land and the Temple” material is primarily from an educational perspective. “The program follows one very clear ideological direction: that we need to quickly build the Temple so the Jewish people will be ‘the best’ in the world. That’s brainwashing, not education,” he says.

The curriculum, says Weiss, places the Temple Mount at the center of things, as a dream that can be fulfilled – even though it is, he says, a crazy fantasy. “We cannot implant such ideas into children and also don’t need to speak about crowning a king, animal sacrifices or the miracles that occurred at the Temple. Judaism is a religion of discourse and study, not of ritual and miracles. The view expressed in the curriculum is mistaken, could encourage paganism and is particularly serious in a democratic country.”

Weiss sees the program as a turning point. State religious schools always used to discuss the Temple, he notes, but “the change is where it is placed, of priorities. Until now, they didn’t place the Temple at the center of the educational program, didn’t stress its importance as being equal to that of the Land of Israel. This is a new and dangerous direction. There are things that are much more important to devote our educational energy to. The Temple has no moral influence. A moral society is a prerequisite for the Temple, and that needs to be the educational emphasis.”

Like Weiss, Berman Shifman is critical of the direction the religious schools’ program is taking. “As a person who thinks that one of the main attributes of Judaism – at least in some of its reasonable versions – is the education to be a [good] person and to deal with ‘tikkun olam’ [repairing the world’], the program incites the students in another direction. The Temple has become a hammer. There is an attempt here to take us back to the previous stage of Jewish tradition, the Temple stage, which was based on relating to blood, race and sanctity that resides in particular places. Not everyone in religious Zionism thinks this way, but there is a certain section, perhaps even a small one, that is seeking to expand its influence by a creeping erosion of the status quo.”

‘No violent expression’

In contrast to Picard and Weiss, who are worried that concrete study about the Temple will spur no less real efforts to get rid of the Al-Aqsa Mosque, Tomer Persico, another research fellow at the Hartman Institute, is less concerned. He sees the program as “an educational expression for small children of rather basic religious beliefs in Jewish tradition. There is no violent expression here toward the Temple Mount mosques.” The curriculum, he says, is seemingly a reflection of discourse about the Temple Mount and the Temple, “which is currently much more popular in religious Zionism than it was 20, or even 10, years ago.” Persico believes there are bigger problems, such as “teaching kindergarten children about the Holocaust.”

The Temple Institute is an educational outgrowth of the controversial institute, which was founded in 1987 by Rabbi Yisrael Ariel. A Religious Education Administration website recommends that teachers use videos produced by the midrasha as social studies material.

The institute – which benefits from staffing provided by women doing civilian service instead of enlisting in the army – organizes lectures, conferences, presentations and workshops about the Temple. The group provides activities for kindergarten kids and older schoolchildren around the country, as well as an exhibition in the Old City’s Jewish Quarter in Jerusalem.

Issues that are simply hinted at or played down in the official ministry curriculum appear to receive explicit attention from Rabbi Ariel. “There is a religious commandment to go up to the Mount at all times,” he told the Ma’anei Haheshua newsletter several years ago. “Before you ask a bright student what he thinks about going up to the Mount, ask him what the distinguished rabbi’s view is regarding the fact that, this morning, the eternal sacrifice has not been carried out at the Temple.” Less abstractly, in an interview with Makor Rishon newspaper last July, Rabbi Ariel said his organization has four high priests, including rabbis who have purchased the appropriate priestly garments and “are prepared to carry out animal sacrifice on the Temple Mount even before the Temple is built.”

Rabbi Ariel has never hidden his views or actions. At one time he ran in the second spot on the slate of slain Rabbi Meir Kahane’s extremist Kach party. He also called on soldiers to disobey orders in the course of the Israeli evacuation of Sinai. He was also suspected of involvement in a plan to take control of the Temple Mount, which is under the day-to-day administration of the Waqf (Muslim religious trust), and had been investigated on suspicion of incitement and sedition. It’s hard to believe that students sent to lectures under the auspices of the Temple Institute’s midrasha are told the full political complexities surrounding Temple Mount.

The institute has received some 1.4 million shekels in Education Ministry funding over the past five years, according to Finance Ministry figures, while the Culture and Sports Ministry has provided a further 814,000 shekels in additional funding to another affiliate of the Temple Institute.

Or Kashti