The many traditions of the reviving liberal arts

Yet, quite surprisingly, the idea of liberal education has taken on new salience in the global higher education debate. This has occurred for several reasons. There is increasing recognition that both the labour force and educated individuals require ‘soft skills’ as well as vocationally relevant content-based knowledge. These include the ability to think critically, communicate effectively and efficiently, synthesise information from various academic and cultural perspectives and analyse complex qualitative and quantitative concepts, among others.

Further, the 21st century economy no longer ensures a fixed career path. University graduates face a diverse, complex and volatile job market. The specialised curriculum is no longer adequate to prepare people for the new knowledge economy, which requires capacity to innovate, and there is growing consensus that this capacity demands a broader range of knowledge that crosses disciplinary boundaries – perhaps a revival of the idea underlying the European medieval universities.

So far, the modest global resurgence of liberal arts education is largely, but not exclusively, concentrated in the elite sector of higher education, although with considerable variation among institutions.

Liberal education

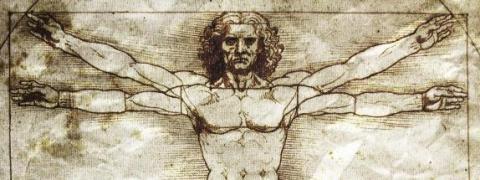

There is no universally accepted definition of liberal education. Most think of it in terms of an approach to knowledge as well as in more detailed curricular terms. Liberal education is typically traced to Western traditions, such as Socrates’ belief in the value of ‘the examined life’, and Aristotle’s emphasis on ‘reflective citizenship’. But as discussed here, there are important non-Western roots of liberal education as well.

Contemporary advocates focus on the value of critical thinking and a broad knowledge of key scientific and humanistic fields as requirements to understand the complexities of post-industrial society. Most broadly, liberal education is contrasted to the more narrowly vocationally-oriented approach to higher education that has come to dominate much thinking in the 21st century. Advocates argue that education is much more than ‘workforce preparation’ – and that contemporary society demands a broader and more thoughtful approach to post-secondary education.

Non-Western liberal arts traditions

Perhaps the earliest example of an education philosophy akin to contemporary liberal education comes from China, where the Confucian tradition emphasised a general education with a broad approach to knowledge acquisition. Two key Chinese education traditions – the Confucian Analects dating back 2,500 years, and traditional Chinese higher education that dates back to the Eastern Zhou dynasty (771-221 BCE) – have elements of what might be called liberal education.

The Five Classics, as they were known then, were featured books that covered many ‘fields of knowledge’. At the same time, Confucian higher education prepared students to take the imperial examinations for the civil service – examinations that called on a general education. Thus, the Chinese higher education tradition emphasised a broad interpretation of the meaning of knowledge while adhering to the Confucian ethical and philosophical tradition. While rarely considered, there are some similarities in approaches to the philosophy of education found in Western antiquity and in Confucian ideas.

Confucius believed that humans were inherently good and thus the purpose of education was “to cultivate and develop human nature so that virtue and wisdom and, ultimately, moral perfection would be attained”.

While the institutional structures, curriculum and purpose of higher education no doubt differed from the contemporary understanding of liberal education, an argument can be made that a commitment to developing students with aptitude that reflected a broad array of knowledge areas links the Chinese higher education to modern ideas about liberal education.

It is also significant that today’s gaokao national university entrance examination in China is a successor to the imperial civil service examinations. While the gaokao, much criticised yet still the norm in China, is hardly compatible with current concepts of liberal education, like its imperial predecessor it requires the student to have a broad knowledge base. In a different context and with very different intellectual roots, Nalanda University flourished in northeastern India for almost a millennium until 1197 CE.

Reflecting both the Hindu and Buddhist traditions, Nalanda hosted lectures by the Buddha and at its height had more than 10,000 students and 1,500 professors. While the curriculum focused primarily on religious texts, broader knowledge was also taught and the university welcomed students and scholars from many intellectual traditions.

Buddhist philosophy defined education as a means of ‘self-realisation’ and a process of ‘drawing out what is implicit in the individual’ by gaining knowledge that would free a person from ‘ignorance and attachment’.

Like the Confucian tradition, Nalanda is another example of a philosophy with a specific focus – in this case on religious knowledge – but with an understanding and belief that meaningful education also requires broader disciplinary perspectives. The oldest continuously operating university in the world is the Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt. Established in 975 CE, the university has been among the most important centres for Islamic thought since its founding.

From the beginning, Al-Azhar not only focused on Islamic theology and Sharia law, but also on philosophy, mathematics and astronomy as they related to Islam. In the 1870s, the university added science faculties as well. At other post-secondary institutions in much of the Islamic world, the curriculum was based on Islamic concerns, but often included other subjects in the sciences and arts – recognising that comprehensive knowledge was necessary for an educated person, reflecting a unified philosophy of education.

As illustrated here, in many classical non-European higher education traditions, institutions and educators were committed to a curriculum that included a wide range of disciplines and knowledge. While the foci, organisation and specific requirements of the curriculum varied significantly, these traditions illustrated a commitment to understanding reality from a range of intellectual traditions.

An international outlook

In the contemporary – and so far modest – reconsideration of the liberal arts globally, rich, non-Western traditions have been largely ignored, even while the debate is taking place in Asia.

The current motivations to reconsider the higher education curriculum are related to 21st century concerns and the necessity of responding to the needs of the labour market. But the underlying verities of liberal education remain as valid now as they were in the time of Confucius, the Buddha and Islamic sages.

Philip G Altbach