Triumph of the Will

The whole colossal exercise was without any rational justification. Tsarist Russia was an inefficient country but, under the impact of rapidly expanding capitalism, was becoming less so with impressive speed. Agriculture was modernising itself without undue suffering. All this was taking place without any interference from the state. Collectivisation halted and reversed the process of improvement, and the losses were not made good for half a century, indeed in some cases never. To collectivise was a specifically political decision, without any economic, demographic, cultural or humanitarian reasoning. It was an absolutist piece of theorising, undertaken without preparation or practical planning, in the arrogant belief that this form of socialism was right.

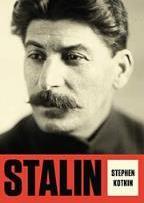

To take such a decision, and to carry it through, year after year, against all the evidence that it did not work, and was wasting life and property in vast quantities, required a sustained act of will of an unusual kind — one is tempted to say a unique kind. Stalin was capable of such an extraordinary act of will and, in Professor Kotkin's opinion, that set him apart from others at the summit of Soviet power at the time. He goes through all the available alternatives. Nikolai Bukharin was hopelessly muddled, especially on agriculture, and believed that the Soviet Union would somehow "grow into socialism" through the New Economic Policy (NEP). In addition, he lacked political skills and an organisational power base. Alexei Rykov, who had been behind the NEP, chaired Politburo meetings, and had been the key figure at the 15th party congress, was a skillful politician but did not believe in collectivisation — he predicted its dire consequences but had no alternative to offer if NEP failed, as it was beginning to do by 1928. Grigory Sokolnikov, the deputy chairmain of the State Planning commission, who had a doctorate from the Sorbonne and spoke excellent French, was a financial expert who defended Soviet policy skilfully at international conferences. But he was a mere individual, with no faction behind him, and no following in the military or the secret police. No one else was in a position to take over Stalin's vote.

Kotkin believes Stalin was saved by the Wall Street crash of October 29, 1929, and by the subsequent Great Depression, in which production in the United States fell 46 per cent, 41 per cent in Germany, and 23 per cent in Britain. "Nothing," he writes, "did more to legitimise Stalin's system." In contrast to the well-publicised misery of the West, the (in reality) far worse miseries of a collectivised Soviet Russia — the famine was always denied to exist — sank into insignificance.

The forced imposition of socialism on Russia was thus, in Kotkin's account, the work of a single man. Stalin was an intellectual, that is, he believed ideas mattered more than people. In the conflict between ideas and people it was the people who must yield, suffer, and, if necessary, die. But the vast majority of intellectuals are weak-willed. What made Stalin different — in this he was unlike any other Bolshevik leader except Lenin — was the overwhelming strength of his will. Hence the transformation of Russia from the confused muddle of capitalism and authoritarian government created by the NEP into the centralised state monolith and tyranny of the Soviet Union, held together by the GPU and the gulag archipelago, was the work of one man. And if Stalin had died in 1928 it would never have come into existence, with all of its enormous consequences to this day.

The only man with a will, at this time, comparable to Stalin's was not a Russian but a German-Adolf Hitler. He too was an intellectual, though his ideology was based in race, not class. His will made possible the creation of an entire system conforming to his idea: the Nazi totalitarian state. The two systems were almost bound to come into collision, and in June 1941 they did. This was the only time in Stalin's life that his will faltered. For a month he surrendered to despair. But his system was sufficiently resilient, and the size of Russia capacious enough, to absorb Nazi advances until Stalin got back his nerve. In this fight to the death between wills — his and Hitler's — Stalin was empowered by a will comparable to his own: Churchill's. Winston Churchill's decision, the day Russia was invaded, to give everything an embattled Britain could spare to keeping Russia in the war ("If Hitler invaded Hell, I would at least make in my next speech a favourable reference to the Devil") made the difference in a narrow equation of power. But that is another story.

Paul Johnson