From seedling colony to Big Apple: Jewish New York history

Published last October, the book is a collaborative effort involving Moore — the Frederick G.L. Huetwell Professor of History and Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan — and fellow scholars Jeffrey S. Gurock, Annie Polland, Howard B. Rock, Daniel Soyer and Diana L. Linden.

It spans over 350 years, beginning when New York was a Dutch colony named New Amsterdam and extends through American independence and the immigration era. The Jews who were part of the story include newspaper publisher Adolph Ochs, who revived The New York Times in the late 19th century; anarchist Emma Goldman, whose fiery rhetoric drew both supporters and opponents in the early 20th century; and CCNY graduate Dr. Jonas Salk, who battled anti-Semitism en route to discovering the polio vaccine in 1955.

The story continues today. According to a 2015 estimate, the metropolis numbers over 1 million Jews within its five boroughs of Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, Queens and Staten Island. “The challenge of writing about New York is that you’re dealing with a city that has more Jews than many nations, most European nations — Britain, France, Germany, Hungary, Austria,” Moore said. “If it were [a nation], it would receive a great deal of attention.”

Herself a native New Yorker, Moore said, “I think New York City has a particular history that makes it key for the development of the US. It’s the culture capital of the US — its economic, political, cultural power. “You define every other place, other places, by the regional influences they have,” she said, but New York’s much larger scale “allows for so much pluralism and diversity.”

Moore is familiar with large-scale projects. Her 2004 book “G.I. Jews: How World War II Changed a Generation,” about the more than 500,000 American Jews who served in WWII, is the basis of a documentary that aired on PBS earlier this year.

She has tackled Jewish New York history before — most notably in 2012, with the three-volume, National Jewish Book Award-winning “City of Promises: A History of the Jews of New York.” She served as the book’s general editor, recruiting as writers the scholars who would later collaborate with her on “Jewish New York” — Gurock, Polland, Rock, Soyer and Linden.

Together, they compiled a comprehensive account of Jewish New York history, which had not previously been written, according to Moore. “Jewish New York” is rooted in this earlier project. Moore said her editor at NYU Press, Jennifer Hammer, asked her to synthesize the three volumes into one. “I cut a great deal,” Moore said. “I built upon the three volumes, the insights they had, and sometimes the language used.”

But “Jewish New York” has a standalone quality. “It’s really a different single volume than three separate ones,” Moore said.

Paring the Big Apple down to size

Moore divided “Jewish New York” into four parts, as well as a visual essay by art historian Linden. The first part involved some of the tightest editing, as it spans the years 1654 — when the first Jews arrived in New Amsterdam, as Sephardic refugees from Recife, Brazil — to 1865, which witnessed the end of the Civil War and the Lincoln assassination.

Moore said that Jews in colonial America and the early republic set “certain important terms [of] how Jews in New York were going to organize themselves” — terms challenged by immigrants in the first half of the 19th century who did not want “one single synagogue,” with the result being “all kinds of alternative versions of how to live Jewishly in the city.”

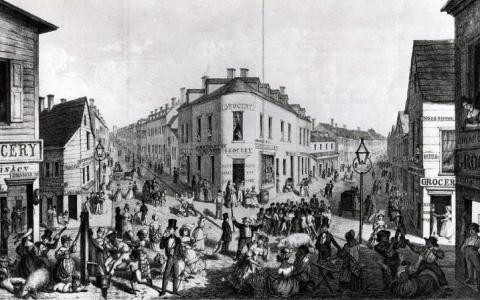

The middle parts of the book represent the 19th and 20th centuries, including the immigrant era, when Jews fled the old country for a promised land represented by Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty. (Moore said the idea of New York as a promised land “ran parallel to Zionism for a number of years” before the US immigration restrictions of 1924.)

Jewish neighborhoods developed — most famously the Lower East Side of Manhattan, but also nearly 50 percent of the city’s Jews lived in Brooklyn. And as for the Bronx, Jews represented almost half of the borough’s population just before the Great Depression.

Jews became the largest single ethnic community in New York, reaching 2 million in a city that could truly be called a melting pot. “There was no majority culture, no majority population,” Moore said. “Jews were not a minority. There is no majority. Everyone is a minority in New York… Groups had different amounts of power at different times, but there was no majority culture.”

In this atmosphere, Jews were able to make lasting contributions in many areas, including City Hall.

“I think Jewish politics in the 20th century lasted a pretty long time, up till the ‘90s,” said Moore, whose book includes New York’s three Jewish mayors (Abe Beame, Ed Koch and Michael Bloomberg) as well as a pair of Brooklyn natives well-known in current headlines. “One of the reasons why I end the book in part with Bernie Sanders and Ruth Bader Ginsburg is that they are exemplars of that political trajectory.”

Moore also noted what she describes as the enduring role of Jewish culture, especially as it contributes to American culture. “When you think of specific individuals, how broadly the kind of intellectual, cultural, art community has been embodied by the city, it’s one of the key accomplishments,” she said.

Examples of these achievements can be found throughout New York. Emma Lazarus’s 1883 poem “The New Colossus” personifies the Statue of Liberty as a beacon of hope to “tempest-tost” immigrants. Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America” was sung at both the Democratic and Republican presidential conventions in 1940.

Moore called cultural impact “a long-term enduring contribution that keeps on restoring itself as younger people grow up in the city, come to the city, want to pursue some aspect of culture — painting, photography, music, writing.”

While the book recounts many accomplishments of New York’s Jews over the centuries, it is “not just a celebration,” Moore said. “It seemed very important to remind current readers, New York Jews among them, that history has dark moments,” she said.

Moore wrote about Jews in colonial New York who owned slaves, and Jews in 19th-century New York who reflected racist sentiments prevalent in the politics of the era. “It’s not just the fact that Jews owned slaves up to the Civil War, they were supporters of the Democrats, who were the slave-owning party at the time,” Moore said. “They did not vote for Lincoln to the extent that we can see. After he died, they changed their attitudes.”

She also discussed Jews who were involved in crime in New York, particularly in the early 20th century; the book notes that the notorious syndicate Murder, Inc. originated in Brownsville. And she reported on racism into the 20th century. “There was racism around schools, neighborhoods, that was something that I had to get a sense of,” she said, including in Harlem, where the population changed from Jewish to African-American.

“Jewish landlords were willing to rent to African-Americans, partly to make a buck,” she said, but “Jews were not willing to live next door to African-Americans. It’s an important part of the story to talk about.”

Moore also discussed the issue of class, which she said sometimes led to intra-Jewish conflict. “It was not just externally,” she said. “Jews tried to form unions in the garment industry. They were fighting Jewish owners, manufacturers. It was a Jewish-Jewish fight. The same was true of the effort to organize in hospitals, when Jewish pharmacists organized. It’s really important to recognize class differences that endure into the 21st century.”

The book takes its narrative up to 2015, examining both continuity and change in the latest century of Jewish New York.

In terms of new developments, Moore looks particularly “at changes where Jews choose to live and work,” noting that younger Jews often choose to live in neighborhoods different from those of their grandparents, which may have smaller Jewish populations. The Jewish population in general appears to be increasing. After an exodus sparked by rising crime in the 1970s and 1980s, the early 2000s saw the population dip below 1 million. But as of 2015, it has surpassed that number once again.

“Assuming that New York is sort of the capital of American Jews will endure,” Moore said. “It has been since the beginning of the 20th century, with the founding of the American Jewish Committee and other organizations that followed. Not all of these organizations continue to exist. But this is the capital city of American Jews. It’s not challenged by any other city,” she said.

Rich Tenorio