Global Talent Flows

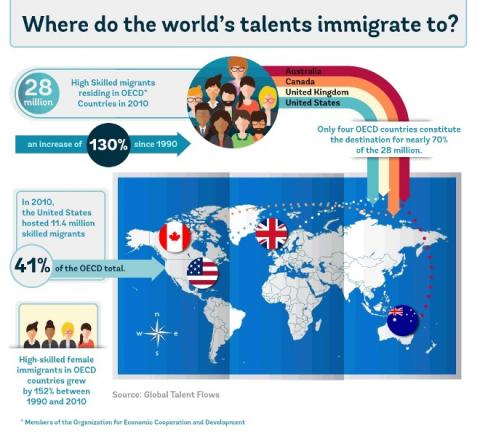

Titled Global Talent Flows, the research found that in 2010, there were about 28 million high‐skilled migrants residing in OECD countries (members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development), an increase of nearly 130% since 1990. Only four OECD countries are the landing destination for nearly 70% of the 28 million migrants.

The study added that the United States alone has historically hosted close to half of all high‐skilled migrants to the OECD and one‐third of high‐skilled migrants worldwide. In 2010, the United States hosted 11.4 million skilled migrants, 41% of the OECD total.

The researchers explained that the forces behind the exceptional rise in the number of high-skilled migrants to OECD countries include the increased efforts to attract talent by policymakers who invest in human capital, the positive spillovers generated by skill agglomeration, the declines in transportation and communication costs, and the rising pursuit of foreign education by young people.

These factors, the researchers argued, also suggest that “high-skilled immigration is often controversial.” They added that for sending countries, the loss of high-skilled workers raises concerns, but the positive side of it is that those migrants “can create badly needed connections to global sources of knowledge, capital, and goods –and some will eventually return home with higher social and human capital levels.”

The research found that many origin countries have limited educational capacities and fiscal resources to train workers or to replace those that have emigrated. It added that countries experiencing particularly high emigration rates of high‐skilled workers to OECD destinations in 2010 tend to be small low‐income countries and island states.

“The reasons why people leave had to do with their living situation,” said World Bank economist Çaglar Ozden, one of the authors of the study. “If you improve and develop the country and improve the overall life of the educated people, they will stay.” “Don’t push them,” he warned, adding that governments can do a lot of things to help bring back the talents. Dual citizenship, he said, is an example of “establishing links” with these talents to make them stay.

Bassam Sebti