Why does the Holocaust memorial plays host to autocrats

Yad Vashem, and the state that houses it, were founded by Jews forced from their homes by chauvinistic nationalism and survivors of the European genocide that was the logical conclusion of those ideas. The museum and Israel flourished in years when those ideas were assumed to have been conclusively discredited.

Today, however, some of those beliefs are rising once again across Europe and in the United States, and Israel finds itself courted by some of their practitioners: right-wing politicians who might stoke animosity to Jews and other minorities at home but who also admire the state of Israel.

The Israel they see is not a liberal or cosmopolitan enclave created by socialists, but the nation-state of a coherent ethnic group suspicious of super-national fantasies, a tough military power and a bulwark against the Islamic world. And these leaders have sought and found good ties with the right-wing coalition currently in power here.

For a sense of this political shift, one need only look at the guest book at Yad Vashem. The memorial is an important stop on the tour for visiting dignitaries, and in the past half-year they have included the nationalist Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orban, one of the most prominent faces of the new political wave, which Mr. Orban calls “illiberal democracy.” Another was President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines, who once compared himself to Hitler and meant it as a compliment to Hitler and to himself. Brazil’s new populist president, Jair Bolsonaro, has said one of his first foreign trips will be to Israel, which means that Yad Vashem can expect him soon. Matteo Salvini, the nationalist deputy prime minister of Italy, is expected in Jerusalem this month.

Employees at Yad Vashem aren’t allowed to speak to the media without permission, and permission to discuss these sensitive matters hasn’t been forthcoming. One senior researcher cut off our conversation as soon as I explained what interested me. The institution’s chairman was not made available for an interview and a spokeswoman simply emailed: “Yad Vashem is not party to the formulation or implementation of Israeli’s foreign policy.”

But inside the offices and archives at Yad Vashem, the argument is getting louder. “There is distress here, and even anger,” a staff member told me, “because many of us see a collision between what we believe are the lessons of the Holocaust and what we see as our job, and between the way Yad Vashem is being abused for political purposes.”

Staffers at Yad Vashem, which receives 40 percent of its budget from the government, are asking themselves and each other questions like: What role should they be playing in the realpolitik practiced by their state? At what point does that role damage their other roles in commemorating and teaching the Holocaust? And how should a memorial to the devastation wrought in part by ethnic supremacism, a cult of personality and a disregard for law handle governments flirting with the same ideas?

The tension inside Yad Vashem broke into public view in June, in the part of the memorial known as the Valley of the Communities, where stone walls commemorate towns whose Jews were murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators. The Austrian chancellor, Sebastian Kurz, was passing the names of Austria’s lost communities when his guide mentioned that some of these very places had recently seen anti-Jewish incidents involving members of the Austrian Freedom Party. That party, whose first two leaders were former S.S. officers, is a coalition partner in Mr. Kurz’s own government.

Mr. Kurz’s Yad Vashem guide, Deborah Hartmann, herself Austrian-born, said to the chancellor that some of his allies were people who “need to be informed what the Holocaust was.” After he left the site, the Austrian embassy reportedly made a rare official complaint, saying Ms. Hartmann had strayed inappropriately into politics. The incident was resolved with an apology from the museum administration.

That episode had barely subsided a month later, when a motorcade arrived carrying Mr. Orban. The Hungarian’s visit drew vocal criticism not just from the Israeli left but also from centrist politicians like Yair Lapid, who recalled Mr. Orban’s praise last year for Miklos Horthy, the World War II leader who allied Hungary with Nazi Germany and collaborated in the murder of the country’s Jews. Mr. Lapid, the son of a Hungarian survivor and the grandson of a victim, said the visit was a “disgrace.”

Before Mr. Orban’s arrival, the administration of Yad Vashem saw fit to issue an unusual reminder that it was the Foreign Ministry that decided the itinerary for visiting officials. In other words: the memorial has no say over who comes. The message suggested an awareness of the rebellious mood brewing in parts of the institution. Mr. Orban’s visit to the memorial went off without incident, though upon departure he was delayed by a group of protesters outside the gates.

Nearly seven weeks later, on Sept. 3, came Mr. Duterte, who cultivates a thuggish persona and, like other members of the current crop of populist leaders, employs a style of outrageous rhetoric and verbal attacks on the press. Like Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel, he sees President Trump as a “good friend.” As this shift in global politics continues to play out, the challenge to Yad Vashem will only grow.

“There’s something going on in the world, and it seems very important,” a second staff member told me. “Trump is part of it, and these leaders are part of it.” The directives to steer clear of present-day politics, this staffer said, were not just unrealistic but also dangerous, ignoring the ways Yad Vashem is used by Mr. Netanyahu, in pursuit of his foreign policy, and by canny politicians from the outside who grasp the value of a photo-op here.

Israel’s first Holocaust researchers were people for whom the subject wasn’t academic, such as Dr. Sarah Friedlander of Budapest, who’d just come out of the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen when she and a few others began Yad Vashem in a three-room apartment in the center of Jerusalem right after the war.

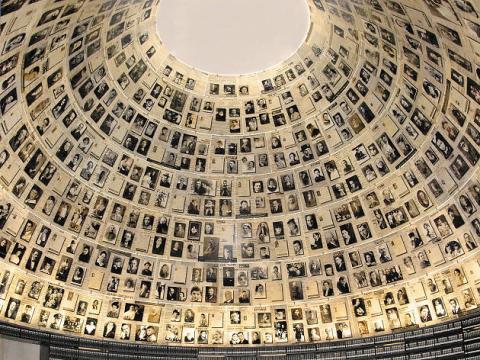

In 1953, when Israel was five years old, Parliament enshrined Yad Vashem’s status and funding in law. After a quarter-century under the stewardship of Avner Shalev, a widely admired former paratroop officer, the sprawling campus now includes numerous memorial sites, an immense archive and a heartbreaking museum designed by the Israeli-Canadian architect Moshe Safdie, which draws about one million visitors every year.

The tension among Yad Vashem’s various roles is as old as the institution itself. “We Jews cannot afford the luxury of mere research work — the awful danger has not passed yet, as we have witnessed in recent years,” the scholar Aryeh Tartakower told the first conference on Holocaust study in Jerusalem in 1947. “It is quite possible — if only I were wrong — that these things could return, and we have to know what to do in order to prepare for the terrible days that are likely to come back.”

For Israelis, Holocaust study has always meant reading the genocide as a warning — and as a compass to direct our actions now. The problem with lessons from the Holocaust is that many can be drawn and they often clash. An American liberal, for example, might say the lesson is universal humanist values — the kind of values that many of us assumed, mistakenly, were permanently ascendant in the world after the war. The Zionist approach has traditionally been that while those values are desirable, they won’t protect Jews after the Holocaust any more than they did when it was going on, and there must be a state with enough power to protect Jews in a brutal world.

That means alliances with other countries that have common interests, whatever their attitude toward liberal values and even toward Jews. Israel signed a peace agreement with the Egyptian leader Anwar el-Sadat, for example, even though Sadat was an authoritarian who’d once been a supporter of Nazi Germany.

The threat to Israel’s Jews in 2018 doesn’t come from rightists in the West but from the Islamic world, and chiefly from the theocratic regime in Iran, which has “Death to Israel” as one of its slogans and whose soldiers and proxies now sit on three of Israel’s borders. Israelis might prefer liberal allies, but liberal leaders in the West have generally been willing to do business with the Iranians and to join dictatorships in isolating Israel at the United Nations. Israel needs all the allies it can get, and leaders like Mr. Orban and Mr. Trump, who share a suspicion of Israel’s enemies, are logical options.

The political calculus is legitimate and one legitimate interpretation of what the Holocaust teaches. The question is where this leaves Yad Vashem.

The conundrum was best illustrated earlier this year in the imbroglio surrounding a law advanced by Poland’s nationalist government to restrict accusations of Polish complicity in the killing of Jews under Nazi occupation. Those most affected are Polish historians, many of whom are colleagues and friends of the historians at Yad Vashem. The same Polish government, however, has become an important ally of Israel.

After an uproar, the Poles watered down the law, and the Israeli and Polish governments issued a joint statement on Poland’s Holocaust history — a strange document of utilitarian historical revisionism aimed at preserving an important alliance in the present.

Yad Vashem’s chief historian, Dina Porat, said she could “live with” the draft with some reservations. For this, she incurred the fury of the institution’s other historians, who publicly excoriated the Israeli-Polish document for inflating Polish efforts to save Jews, for suggesting a parallel between anti-Semitism and “anti-Polonism” and for other instances of “highly problematic wording that contradicts existing and accepted historical knowledge” — or, in less diplomatic language, lies.

In a similar episode, a new Hungarian Holocaust museum called the “House of Fates” under construction by the Orban government has drawn sharp criticism from Yad Vashem because it appears to play down the role of Hungarians in the genocide. Robert Rozett, one of Yad Vashem’s historians said the project involves “a grave falsification of history.” Dr. Rozett had been given the job of guiding Mr. Orban on his visit earlier in the year.

Then, just this week, Israel’s Channel 10 reported that senior Hungarian and Israeli officials were meeting to come to a “consensus regarding the museum’s narrative,” drawing accusations that the Netanyahu government was again using Holocaust history, and Israel’s perceived role as an arbiter of that history, as currency in the marketplace of international politics.

One of the scholars behind Yad Vashem’s response to such matters is Yehuda Bauer, the dean of Israeli Holocaust scholars. Mr. Bauer escaped Czechoslovakia as a child with his family in 1939, and his sharp intelligence is undimmed at 92.

Yad Vashem, he told me, has long done an admirable job of walking a tenuous political line, remaining faithful to history while navigating the politics of this country. While Mr. Bauer agreed that Yad Vashem is being used both by the Israeli government and by visitors like Mr. Orban and Mr. Duterte, he said the memorial had no choice: The Foreign Ministry sets the guest list, and the memorial’s policy as an educational institution has always been that anyone who wants to come can come. “It’s important to us to show them these things, even if it’s people we wouldn’t invite to dinner,” he told me. When in the 1990s the possibility arose that Yasir Arafat of the Palestine Liberation Organization might visit, he recalled, the memorial was in favor: “We said, if he wants a guide, no problem, we have enough Arabic speakers.” (Mr. Arafat never came.)

While the welcoming of controversial leaders might draw criticism from the public or unhappy staff members, refusing them or confronting them could draw the ire of the Israeli government, which is a far greater concern for a practical reason not necessarily apparent to outsiders. Yad Vashem’s chairman, Mr. Shalev, will be 80 next year. The job is a political appointment. Mr. Shalev, put in place under a Labor government in 1993, is understood to be a man of Israel’s old moderate establishment. His replacement could bring the institution more closely in line with Mr. Netanyahu’s political program. Insiders at Yad Vashem understand that this is both a reason that Mr. Shalev isn’t retiring and a reason for extreme caution in handling these current controversies and those sure to come.

The idea of bringing dignitaries to pay respects at Yad Vashem is related to the tradition in other countries of laying a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknowns — an uncontroversial recognition of a piece of history important to the host country. Yad Vashem might want to be a memorial of that kind, but it can’t be, for the same reason its historians are constantly engaged in wars in the present: because this history still isn’t in the past.

Matti Friedman