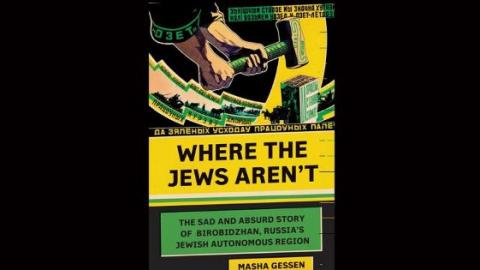

Where the Jews Aren’t

The Jewish Autonomous Republic was established 8,000 kms (5,000 miles) from Moscow, in a place whose the soil was not suitable for farming and whose current residents were Cossacks – a people not known for their partiality toward Jews. Seeing on a map that the border with China is only some 50 miles’ distance, the only seeming advantage to living there is that one would be well placed to order take-out Chinese.

The very outlandishness of the idea makes it seem like a natural subject for a book, and Masha Gessen would seem to be the ideal person to write it. Born in Moscow in 1967, she moved with her Jewish family to the United States in 1981 and was educated there. In 1991, when the Soviet Union disbanded and the president of the new Russian republic, Boris Yeltsin, invaded Chechnya, Gessen moved back to her birthplace to cover the action. It was only in 2013, when the Russian parliament, responding to the hatred of gays being fanned by the Putin regime, began considering measures to take away the children of LGBT parents, that she and her female partner decided it was no longer safe for them and their two children in Moscow. They returned to New York.

Throughout her career, Gessen has excelled in helping American and other Western readers understand Russian culture and society. She has reported on the eroding human-rights situation; the arrest and imprisonment of the all-girl band Pussy Riot after its members staged a performance in a Russian Orthodox church; and her 2015 book “The Brothers” examined the background of the two young men, Muslim immigrants from Chechnya, who set off a fatal bomb at the 2013 Boston Marathon.

Inevitably, Gessen, author or editor of 11 books, writes about Jews – even about her own family – as the experience of the Jews in 20th-century Russia (and in the preceding centuries, too) serves in miniature to exemplify all that was cruel, arbitrary and self-defeating about that country, particularly during the Stalin years. (Under Putin, there are not enough Jews left for the regime to turn them convincingly into an existential threat.)

At one point early in “Where the Jews Aren’t,” she refers to a previous draft of the book, completed in 2010. Considering how prolific she is, her delay in publishing this short book made me wonder if she had put it aside when she found herself short of material to tell the Birobidzhan story.

In fact, probably less than half of the book is devoted directly to that subject. The rest is partly personal memoir, though none of her family ever lived in the province, and biography – of both Yiddish writer David Bergelson and, to a lesser extent, the historian Simon Dubnow. Bergelson is a reasonable choice, since he allowed himself to become a cheerleader for Birobidzhan (big mistake), but Dubnow, involved as he was with the Jewish Question, does not seem to have been engaged with this particular solution to it.

Which is not to say that “Where the Jews Aren’t” is not worth reading. Even if the framework holding the book together is flimsy, the details, the insight and the writing itself are not. Gessen has the subtlety, honesty and tragic sensibility necessary to take a period and a society that are dripping in cruel irony, and to tell her stories with great affect, without being treacly or preachy.

Bullish on Birobidzhan

David Bergelson was a Ukrainian-born secular Jew who had tried writing in Hebrew and Russian before settling on Yiddish. He saw the language as a vehicle for uniting the Jews of Eastern Europe, and around which could be built a national culture. Bergelson was not impressed with the Zionist aspiration to establish a homeland in the Land of Israel, and was convinced that if the Jews sought safety in the U.S. they would end up assimilated.

He allowed himself to become enamored of the Birobidzhan scheme after a sojourn in Berlin, where he enjoyed professional success and life in general until just weeks before Hitler came to power. A short time later, he returned to Moscow and began to re-ingratiate himself with the Soviet regime. Gessen doesn’t tell us much about the birth of the Birobidzhan plan, which may be because the records just don’t exist (or remain classified). However, a delegation of agronomists did travel to Birobidzhan in 1927 to check out its suitability for settlers, and on its return, prepared an 80-page report for the government, which Gessen quotes from. Almost like the biblical spies sent into Canaan, they reported that the area had inappropriate terrain and weather for farming, was overrun with insects and had a native Cossack population that was unlikely to welcome Jews as neighbors. If the Jews were to be moved to Birobidzhan despite their counsel, they suggested, hold off on bringing them until the infrastructure was installed and some light industry established, as very few had agricultural experience, and then settle them there gradually.

Suffice to say that none of their advice was heeded, either. The first trainload of migrants, most of them unemployed Jews from Depression-era Ukraine and Belarus or Yiddish speakers returning from abroad, pulled into Tikhonkaya station in April 1928. Most of them didn’t stay long, but of those who did, some were sent to populate Birofeld, “the first Jewish collective farm in the Far East,” writes Gessen. Equipped with neither proper experience nor tools, many of them were gone by the end of the following winter, although they were quickly replaced by new victims.

Bergelson, though, remained bullish on Birbodizhan, perhaps because he never intended to live there. After his first tour, he announced his intention to write a book about the new Jewish homeland – once he was back in Moscow. In January 1935, he prepared an eight-point manifesto, “Why I Am in Favor of Birobidzhan,” which was published in the Warsaw-based Yiddish paper Der Fraynd.

Gessen reprints the manifesto, most of which speaks in lofty language about the benefit the province will bring to the socialist enterprise and to the Jewish people. Point seven, however, reads: “Refusing to work in and on behalf of Birobidzhan would be both against my own personal interest and against the entire Soviet collective” (emphasis is mine).

That one, admits the author, “breaks my heart.” Bergelson, she explains, “was a cornered animal,” having returned only a few months earlier to Moscow. “He had voluntarily surrendered his freedom … in exchange for the protection of a state that offered him a home,” she writes. Gessen would have done better devoting the entire book to Bergelson, for whom she reveals great empathy. She doesn’t judge his self-serving behavior, or what was at best extreme naivete. Having grown up in the Soviet Union, albeit a gentler one than Bergelson’s, she is not so arrogant as to condemn a man for trying to stay alive to support his family, or for having the bad luck to have been forced to choose between Hitler and Stalin.

Short-lived revival

As for Birobidzhan, it is the perfect answer to a question in a trivia contest, but there doesn’t seem to be a lot to say about it. Two years after Bergelson published his manifesto, the Great Terror began and nearly all the Jewish leadership of Birobidzhan found itself purged. Whereas a moment before, populating a border region with Jews was deemed in the interests of the state, now it constituted a security risk. The Yiddish conference scheduled for the winter of 1937 was postponed (for good), and one after another, the local political stars of Jewish Birobidzhan disappeared from the firmament.

Bergelson lay low and survived the purge, resurfacing in 1941 after Nazi Germany attacked its erstwhile ally and the Soviet regime turned to the country’s Jewish intellectuals to convince their brethren overseas – in particular those in the U.S. – that Russia was on the front line in the fight against German fascism and needed to be supported. Members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, to which Bergelson belonged, traveled the free world selling the cause to the Jews.

When the war was won and the former allies reverted to a tense modus vivendi, Stalin purged all the members of the Anti-Fascist Committee. After lengthy imprisonments and a set of show trials, they were all executed on what became known as the “Night of the Murdered Poets” in 1952. Bergelson’s luck had finally run out. He was tried and convicted of “nationalism,” a capital crime.

After the war, Birobidzhan did have a brief revival. When tens of thousands of Jewish survivors returned from German captivity to find their former homes in Ukraine and Belarus occupied by others, the solution arrived at was to ship many of them off to Birobidzhan. Hundreds of families arrived, and the region underwent another revival of Yiddish culture. That, too, was short-lived, as the nationalism for which Bergelson was killed a few years later also became a reason for Jews to be afraid of speaking Yiddish in public.

“Around five years after the end of the Second World War,” writes Gessen, “the Sholem Aleichem Library of the Jewish Autonomous Region staged a book burning … in its courtyard, to destroy every Yiddish-language book that had been found in the region.”

When Gessen paid her own visit to Birobidzhan in 2005, she found the infrastructure for Jewish tourism, but few remnants of actual Jewish life for visitors to enjoy. Some thousands of Jews may still live there, but most got out when they could after 1990, and came to Israel. Of the roughly five people in the province who remained actively involved in Jewish culture, Gessen learned, only one speaks Yiddish.

David B. Green