Tel Aviv, the city that never stops dining

“This is our own small cultural center,” says Dunevich. “We have our music, the books, a large-screen television and people who come to visit. Even when they’re renovating the large municipal cultural center, the play goes on here and we cook the best food in the world. Here we don’t eat boiled chicken, endlessly reheated potatoes or burned carrots. This is the home of people who love to eat.”

Ruti Dunevich is the mistress of the kitchen. The attractive woman who danced in Berta Yampolsky’s troupe in addition to working as a school nurse looks as though she emerged from one of the theatrical operas she loves. Everything is colorful and bold − hair and eyebrows dyed a bright red, flowered dresses, necklaces and earrings that she makes herself − as are the appetizers she serves to guests.

In the kitchen there are collections of exotic spices, placed in boxes and carefully cataloged, kitschy toothpicks and hundreds of other attractive eating utensils. Ruti Dunevich continues to go to specialty shops to buy the ingredients she needs for the dozens of delicacies seen in the refrigerator and pantry − we swear we’ve never seen such an orderly array of good things to eat.

To avoid problems, she says it's better to stay away from the large supermarkets. One shop specializes in importing pickled fish; reasonably priced Italian wines can be purchased from a veteran beverage merchant on De Pijoto Street; and every vegetable, cut of meat or fresh fish is carefully chosen.

Italian food is the greatest love of Dunevich, who learned to read and write Italian fluently in order to understand the opera librettos and to read beloved works in the original language. But foods from all over the world have also attained citizenship in her home kitchen, as long as they delight the palate of the masters of the house.

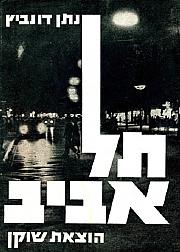

The loving husband, her No. 1 admirer, as he puts it, sits in the kitchen when she cooks, “ready at any moment to taste and express an opinion.” Only in the past year, due to ill health, have they stopped going out to the restaurants of Tel Aviv, which they have frequented together during more than 50 years of marriage. They miss Yaron Shalev’s Toto, the now-defunct Mika, and the days when they returned from the Romanian restaurants on Hakishon Street drunk and happy. Those restaurants, as well as their predecessors, star in Natan’s new book, “From a Soda Kiosk to a Chef’s Restaurant − 100 Years of Food in Tel Aviv” (published in Hebrew by Achuzat Bayit).

“I started writing this book two years ago,” he says, “when I realized how important food has become in the present leisure culture. I thought that someone who was born in the early 20th-century in Little Tel Aviv, and saw the beginning with his own eyes, could provide an interesting perspective on the subject, due to his age and experience. First of all it’s a book about personal experiences. Some of it was taken from the column I published for years in Haaretz, which discussed people and places.

“But when I began writing I looked for archival material and historical sources to complement my memory. You can’t rely on memory alone, because it’s deceptive. This is first and foremost a book about people who brought their native cuisine with them from all over the world. There aren’t many examples of cities with a population of slightly over 400,000 that have ingredients, stores and restaurants representing over 50 countries, from the North Sea to New Zealand.”

Natan Dunevich was born in 1926 in Tel Aviv, to a well-to-do family of grain merchants from the Russian city of Saratov on the banks of the Volga River, who decided to immigrate to Palestine after the rise of anti-Semitism in their native land. His father, who built the family home on Nahalat Binyamin Street, was manager of a bank that provided loans to small businesses in the new city. His mother, he writes in the introduction to the book, gave birth to him prematurely − on the dining room table at the home of the local doctor.

“Mother was a gifted cook, and she used to prepare genuine Russian cuisine, not Russian-Jewish cuisine, which has remained etched in my memory forever. In the summer Father would give Mother a vacation from the kitchen and take us to restaurants every day. That’s how, although I was young, I became personally acquainted with the restaurants and the people involved in the culinary history of Little Tel Aviv.”

In 1944, when he finished his studies at Gymnasia Herzliya high school, Dunevich began writing for newspapers; in the summer of 1947 he joined Haaretz, where he launched an impressive and varied journalistic career than lasted for over 50 years. In 1954 he suggested to his editors that he publish a personal column of human interest stories about life in the big city (“The model was the column of the American Jewish journalist Meyer Berger in The New York Times, and in those days it was a revolutionary innovation in the Hebrew press”) which was called “My Town.”

In 1956 he married Ruth Rotter; they have two children, attorney Shira Dunevich and mystery writer Roni Dunevich. In 1963 he became the founder and first editor of the Haaretz weekend supplement, the first such magazine in Israel.

Dunevich: “We’re talking about the days before television. Reshet Bet on Israel Radio, which was a ‘lighter’ channel, was starting to attract listeners, and Haaretz was in need of more readers. At the time the publishers brought a modern printing press that was supposed to be able to print magazines in color, and it was decided that a small supplement called Biduron would be added to the Friday newspaper. Since I was writing a regular entertainment column at the time called ‘Kokhavim Umazalot’ (Stars and Heavenly Signs) I was asked to edit Biduron, which was supposed to be a small entertainment magazine the size of a school notebook. I thought it was an opportunity to create a real magazine, and convinced the managers at the newspaper.

“They sent me to London, to sit on the editorial board of the Sunday Times magazine, considered a leader in its field; I learned the ABCs of editing a magazine there. When I returned to Israel I realized that a cast had to be found for this show. I received almost no cooperation from the daily and started to recruit the best people from outside: Silvie Keshet, Michael Ohad, Roman Frister, photographer Yaakov Agur and caricaturist Ze’ev [Yaakov Farkash].

“About a year after the supplement first came out, and was very successful, Amnon Rubinstein, today Prof. Rubinstein, suggested that we hire Rene Mokadi − a teacher of guitar, French and other languages, who in the past had been a sailor on cargo ships and ate at every port − as a restaurant critic. Mokadi signed his columns with the name R. Istanis (aesthete). As opposed to today’s critics, he was anonymous [when he went out to eat]; people didn’t prepare special meals for him that differed from those of the ordinary customers. Gershom Schocken approached me personally after a number of columns and asked that Mokadi include in his critique his impressions of the condition of the bathrooms, which were terribly neglected at the time even in the expensive restaurants.”

The thick book by Dunevich that is now available in book stores does not presume to document Tel Aviv’s culinary history chronologically, but does aim to describe the social history of the city via its eating habits.The book has 44 chapters, dedicated to such subjects as the history of Levinsky Street, the “ice age” before the electric refrigerator, the golden age of steak joints and the modern sushi revolution. The most fascinating parts are those that describe, compassionately and with sensitivity, the fate of food industry people, since fortune did not always smile on restaurateurs.

Other intriguing sections are those devoted to the distant and insufficiently documented past of local culinary history. In 1958 the so-called Tel Aviv Gastronomic Circle held a festive banquet to encourage excellence in local cuisine. In 1968 the fifth World Congress of Gastronomy was held in Jerusalem (the State of Israel competed with Switzerland and Mexico for the right to host it). And the 1960s and ‘70s saw the emergence of the first local chefs who wanted to raise their own vegetables as ingredients for their dishes.

Is the common perception that the local culinary revolution has only really taken place in the past two decades mistaken? Dunevich thinks not. He says there were initial attempts by pioneer gastronomists from the early days of the city, but the vision was shared by only a few people.

“In the beginning most of the population of Little and ‘medium-sized’ Tel Aviv ate at home, or brought food from home to work. There were also restaurants and delicatessens selling delicacies from all over the world − business was so lively that a Portuguese sardine cannery even sent over cans bearing the pictures of [Zionist leaders] Herzl and Sokolov − but few people were wealthy enough to be able to afford them. Alongside them, popularly priced restaurants gradually opened, which subsidized and supplied filling food for workers and clerks from the lower and middle class.

“The huge gaps between the upper and lower classes shrank during the early years of the state, and with the flourishing of Mizrahi cuisine [originating in North Africa and the Middle East], which pushed out European cooking. At the table with hummus and tahini and grilled meat, people of all classes sat shoulder to shoulder. In the 1970s the culture of espresso, pizza, hamburgers and Chinese food first emerged, but only in the 1990s − thanks to outstanding individuals such as chef Tzachi Buchester − the dominance of television and the trend of traveling abroad, did the real culinary big bang take place.”

To my taste - Dunevich answers the culinary questionnaire

My last meal on earth: “Since I will be embarking on a long journey, to somewhere beyond the clouds, I will choose food that is not heavy, rather the kind that preserves the original and high-quality flavor of its ingredients. Thin and crisp Viennese schnitzel made with veal, potato puree, homemade cucumbers pickled in brine, and for dessert: vanilla and cherry ice cream with Belgian chocolate flakes. I’ll finish with a cold shot of peach grappa.”

An unforgettable childhood memory: “On Friday afternoons my late mother used to bake cakes and small pastries for Shabbat. Everyone else went to visit my grandmother and left me alone in the house with a large tray of apple halves covered in batter. As soon as my parents left the house my feet led me to the heady fragrances coming from the kitchen. I picked up one pastry, hot and smelling of cinnamon, I went to my room and already on the way I yearned for the rest of the pastries on the tray. When my parents returned they saw an empty tray, a guilty look and a big belly: 24 pastries had disappeared as though they never existed! Father didn’t conceal his anger, while Mother looked at him and said, ‘Haim, the main thing is that the child doesn’t get sick.’ From that day on I had to accompany my parents on their weekly visits to my grandmother.”

An unforgettable eating experience: “In the summer of 1949 I was invited by an American reporter, for whom I had helped to collect material for an article, to lunch in the new French restaurant Ciro’s in the Central Hotel. In the early afternoon we were the only guests, and the head and only waiter had all the time in the world. He approached our table, dressed in a black tuxedo, a starched white shirt and a black bow tie, with a professional smile on his nicely shaven face, which smelled of aftershave. My host called him by his French name, Michel, and whispered to me that the man had previously been a waiter in Bucharest.

“When I dared to ask about the dish he had suggested in fluent French, cocktail de crevettes, his disdainful glance said it all: I’d be better off returning to the treetops. My host, a man of the world, explained to me, the native, that it was a kind of seafood, and that in English it was called shrimps. Michel brought two cups with the ‘French’ creatures in a tasty pinkish sauce. That was the beginning of my long friendship with seafood.”

An unfulfilled food fantasy: “I want to return in a time machine to my childhood, to my mother’s wonderful food. Not that I’m suffering now, God forbid. I’ve been married for 56 years to Ruti, who is famous for her wonderful cooking.”

I’ll never touch: “Lamb tongues or ox testicles.”

An unforgettable cultural food memory: “From ‘Babette’s Feast,’ the charming Danish film about the Parisian chef who is forced to flee France penniless, and prepares a royal feast for the inhabitants of a remote village in Denmark. I watched and was envious of them. The person sitting next to me continued to eat popcorn.”

Tel Aviv’s pioneering eateries

The first delicatessen: Pesach Shor’s grocery, 18 Herzl St., Tel Aviv, opened in 1927. In the late 1920s Shor, an importer whose business involved bringing in delicacies from Europe, Egypt and Lebanon, moved his Jaffa store to young Tel Aviv. In the spanking clean shop, he sold cheeses and butter from Holland and Switzerland, sausages and canned fish, fruit Sharona quarter of the city.and vegetables. Under the counter Shor secretly kept pork supplied to him by a German from the Sharona quarter of the city.

The first steak restaurant: Victoria’s Restaurant, Salameh, Tel Aviv, opened in 1954. Victoria, a woman without means, of Bulgarian origin, made a meager living from the sale of meats grilled under a canvas tent in an empty lot in the south of the city. The steaks and skewered meats attracted night owls, and within a few years her business moved to a permanent location at 35 Petah Tikva (now Begin) Road and began to go downhill. Eventually the place switched owners and names until, in 1968, it was bought by an energetic redheaded restaurateur named Moshe Kruvi, who called it Mi Vami.

The first pizzeria: Pizza, 93 Dizengoff, Tel Aviv, opened in 1957. Entrepreneur and restaurateur Alex Shor was the first to open a modern, well-designed fast-food restaurant of this type, with a large, shiny neon sign in front. The crowning glory was Italian-New York pizza; masses of people streamed in and waited patiently for a hot slice.

The first Chinese restaurant: Rickshaw, corner of Tayelet Hayam and Trumpeldor, opened in 1957. On the top floor of the Central Hotel, restaurants and their owners changed at a dizzying pace. In one of those incarnations the place that claims the title “the first authentic Chinese restaurant in Israel” opened. The cook was Lao-Tse Marom, the daughter of parents of Russian Jewish and Chinese descent, and mother of the former Israel Air Force commander Eliezer (Chiney) Marom.

The first hamburger joint: California, Frishman St., Tel Aviv, opened in 1959. The eatery owned by Abie Nathan − the human rights activist and founder of the Voice of Peace radio station − was the first to offer a non-kosher American-style hamburger, with french fries and ketchup. Cheeseburgers were also on the menu.

By Ronit Vered