Is Religion 'Old-Fashioned' and 'Out of Date'?

But more importantly, these options are conceptually meaningless. When the poll says "all of today's problems," is it referring to political gridlock? America's inefficient healthcare system? "Mo' money"? The concept of "out-of-date" or "old-fashioned" is even more troubling: It's built on a very particular idea of history, which is that human civilization has been progressing linearly toward a modern age. The underlying assumption is that secularization theorists are at least somewhat correct: Religion is somehow "old" or pre-modern or even anti-modern, whereas secular life is "new" or fully modern or post-modern. Even though the poll is ostensibly asking respondents to say whether they think this is right, the premise of secularization theory is baked into the way they asked the question. That's why it's framed in terms of "new" and "old"—or, in other words, relevant and irrelevant.

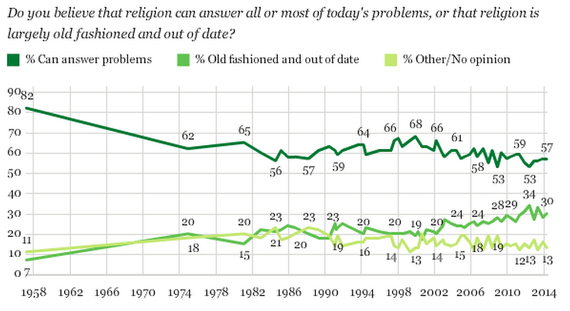

But, of course, Gallup asked the question (and, implausibly, has apparently been asking the same bad question since the 1950s), and if there's a poll question, so shall there be a graph:

What we're meant to take from that graph, presumably, is that doubts about religion—and, along with it, secularization—are on an undeniably upward trend. As many as a third of Americans think religion is "out of date," so that must mean faith is slowly but surely going out of style. This is only true in the most general possible sense: When respondents in a 2012 Pew survey were asked whether they "believe in God or a universal spirit," 92 percent said yes, with varying degrees of certainty; only seven percent said no, and only two percent said they didn't know. When asked the question in a different way—"What is your current religion, if any?"—a little more than two percent of people said "atheist" and three percent of people said "agnostic," while almost 14 percent said "nothing in particular."

As the Pew researchers pointed out at the time, this represented a growth in the religiously unaffiliated over the course of five years—the group of atheists, agnostics, and "nones" grew by about four percentage points. So, in the sense that the Gallup data tracks this same, general directionality of religious trends in the United States, it's not wrong, per se. But even the Pew poll, which was much more carefully worded, reveals the trouble with trying to data-ify faith: Two slightly different questions in the same survey yielded two totally different estimations of the country's percentage of non-believers: Seven percent of people said they didn't believe in God, but only two percent actively identified as "atheists."

That ambiguity is totally masked when you're looking at a neatly drawn graph with definitive-looking trend lines. In theory, the pollsters at Gallup would probably be very comfortable with admitting the limitations of social science: Correlation doesn't indicate causation, polls come with bias, etc. etc. But when you ask a question this imprecise, and package the results this definitively, those words of caution get totally lost. Even though it's one question in one poll in today's utter ocean of survey data, this is a perfect example of the impulse to try and measure every aspect of belief and ideology, as though quantitative social science is the only legitimate way to gain insight about the world. In the worst case scenario, what we get instead is a vague impression of people's vague impressions of a huge, complex concept—and a neat, clean graph to make us feel more in control of the truth.

Emma Green