The real point of no return in the Jewish-Arab conflict

Cohen, a lecturer on Middle Eastern studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, cites S.Y. Agnon’s famous line regarding his own, changed attitude toward the Arabs in the wake of the 1929 riots: “Now my attitude is this. I do not hate them and I do not love them; I do not wish to see their faces. In my humble opinion, we shall now build a large ghetto of half a million Jews in Palestine, because if we do not, we will, heaven forbid, be lost.” Cohen notes that these are early signs of the separation mind-set, which became official Israeli policy at the beginning of the 21st century. Yet, it is doubtful whether, after those riots, it was still possible to realize that which Agnon aspired to.

“Tarpat” is a spectacular stew, with every ingredient tossed into the mix, for discussion. The triangle of Mizrahim-Ashkenazim-Arabs (Yosef Haim Brenner: “What good will the one language do? One language for whom? For me and Sephardim? And are we really one nation with them? Say what you will: In my opinion, that is another people entirely”); the subject of Zionism as colonialism; the direct connection between 1929 and 1948, the year of independence; Uri Zvi Greenberg, Jacob Israël de Haan, Albert Einstein and Yeshayahu Leibowitz, Gershom Scholem and Brit Shalom; desecration of mosques; Suha Arafat and Thelma Yellin; and the reality of Arabs prostrating themselves on the doorsteps of Jewish homes in order to preserve the lives of the residents within, and of Jews spiriting Arab families away and saving them from being lynched.

Cohen quotes the witty words of the British judges at the trials following the 1929 events, who try with all their might to understand who was responsible for the first kill (spoiler: all sides were). He writes about the age-old dispute over the Western Wall, about Chabad at the forefront of the fight against Zionism, about pro-Zionist Muslims in Hebron and about the Tomb of the Patriarchs there, about the issue of land purchases from the Arabs, about morality and moral superiority, about massacres of all kinds – and specifically about the horrifying massacre in Hebron – about truths and lies, about the press (“No understanding between you and us is possible unless the Balfour Declaration is nullified,” the newspaper Falastin wrote in September 1929. “There shall be no understanding before you realize that Falastin is not part of Wild Africa, and murdering people is not as easy as in Rhodesia and the rest of the countries settled by Negroes, who do not put up any resistance”), about the Koran and about victim-hood and hangings.

The book is organized according to the main sites where the uprising occurred: Jaffa and Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Hebron, Motza and Safed. But its frame narrative is actually an unknown story: The murder of the Awan family in Jaffa by Simcha Hinkis, a “Jewish police constable,” as the case is described in the book “Biladuna Filastin” (“Our Land Palestine”), a geographical encyclopedia by Mustafa Murad al-Dabbagh.

Cohen traced the life story of the man who murdered the Awan family, Hinkis (who was sentenced to death, but saw his sentence commuted). This incident brought to his mind several burning questions. Cohen realized that from a Palestinian perspective, the story of Tarpat is different from the one he knew. And this is what interested him: How did it happen that the Arabs perceived reality so differently from the Jews?

The book also makes gentle leaps forward – up to the victory of 1967 and sometimes nearly to our day – but always in an almost silent manner, as though it is too early and we cannot yet judge the present or even understand it. After the 1929 riots, Cohen describes Yaakov Pat, a senior member of the Haganah (Israel’s pre-state militia), who was traveling by train from Haifa to Egypt, when he encountered Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini. “I went back and stood at the window and the smug ugly face of the mufti looked back at me. Here, come a step closer to me, and stick out your hand and act (for this time you have a weapon!),” he imagined to himself.

Pat debated whether to take hold of the weapon and take the mufti’s life, until suddenly his “thinking cleared. It was clear to me that I was not allowed to do the deed, not while I am on duty and fulfilling an assignment. To the contrary. It is clear to me it would be an act of treason.”

Haganah soldier Ephraim Tzur’s soul, too, yearned to murder the mufti, as Cohen relates. Tzur sent a letter to Rachel Yanait: “I wrote that I can and want to finish off the mufti.” But her response was firm: “For God’s sake, do not do that.” Even in insane times such as those could “targeted assassination” have been deemed a foolish, immoral action. Even treasonous.

The land is one

There will be readers who will fidget uncomfortably in their chairs as they read about Jews who perpetrated reprisals against Arabs, and even lynched them, and about Arabs who saved Jews (and vice versa). Cohen’s story is not biased with regard to the truth of any particular side, maybe because there aren’t really two “sides.” No border can really pass between these two peoples, because the land is one, and the story – convoluted and complex as it may be – is shared by both.

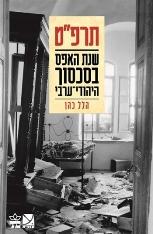

Cohen’s readers have undoubtedly heard about the massacre of Hebron’s Jews in 1929. Whoever visits the museum in Hebron today, which is housed in Beit Hadassah, will be able to see photographs of dead and injured Jews, people without limbs, and even get a close look at the very axes that were used, according to the museum’s organizers, by the Arab assailants. On my visit to Hebron last month, I saw on one of the street signs that relate the city’s story to pedestrians a marker about 1929, headed “Destruction,” with the following text: “Arab rioters massacre Jews. The community is expelled and destroyed.”

“Tarpat” makes use of Israeli scholarly works, testimonies from the archives of the Haganah, minutes from Mandatory-era courts, clippings from the archives of such newspapers as Haaretz and Doar Hayom, medical files and more. Cohen juxtaposes the reports written by Jews against a host of Palestinian sources from the period and from our own time, and shows – time after time – just how often history, as the people involved tell it to themselves, is partial at best, and even misleading. By means of writing, we sometimes perform an action that is ostensibly the opposite of writing; if it seems at times that silence is concealment, then these books “are primarily engaged in concealing by means of writing.”

So, Hillel Cohen set out in search of answers and came up with a major question. And perhaps this is what distinguishes his book from many others written about the conflict over the years. He uses few maps and diagrams, offering little prescriptive advice. He also refrains from expressing remorse, lecturing or becoming mired in despair. Cohen does not forget that as an Israeli Jew, he cannot write from a “neutral” viewpoint or even – for the sake of the intellectual game – cross the lines. He doesn’t want to, either. But he understands something basic, which many people choose to ignore systematically: In order to plan your actions (as a person, as a people), you must understand the other side – its desires, its frustrations, its secret feelings and its anger. He understands that, more than it is important to understand what actually happened and who suffered the first fatality, one must understand how each side perceives the actions it performed and those performed by the other side.

“Over everything hung one unequivocal fact,” he writes. “The sages of the East, the immigrants from the Maghreb, Zionist ‘pioneers,’ members of Hasidic courts, intellectuals from Eastern Europe, Maghrebi fishermen and Lithuanian activists, all as one worked to expand the Jewish community in the country and to transform it into the land of the Jews. And even if not all of those Jews were necessarily aiming to found a Jewish state, and not all viewed the Arabs as enemies, this activity as a whole created in the Arabs of Palestine a terrible sense of intimidation, which grew increasingly harsher after the Balfour Declaration and the British occupation.”

The Israeli image of realityis overly simple: It has good guys and bad guys, and even if we have transgressed here and there, “they” were wrong to refuse the UN Partition Plan, “they” were not wise enough to accept all the good things they were offered at Camp David, “they” have proved over and over again that we have no partner.

Jules Michelet, the 19th-century French historian, wrote: “It is a fact that history, in the progress of time, makes the historian much more than it is made by him. My book has created me. It is I who became its handiwork. The son has produced the father ... If my work resembles me, that is good. The traits which it shares with me are in a large part those which I owe to it, which I took from it.”

The book “Tarpat,” with its insights, its tales and the humanity that is revealed through them, may have “created” the historian that wrote it, but it has also succeeded in doing more than that: It elevates the reader to the position of the one holding the ends of the threads, turning him into the one who weaves history and brings it back to life. It has thereby transformed him, the reader, into the creator of his own story, or into his own creator (as an Israeli, as a reader, as a person) on a small scale.

Moshe Sakal

Moshe Sakal’s new novel, “Hayahalom” (The Diamond), is forthcoming in Hebrew from Keter Publishing.