Primo Levi, the Holocaust and today's world

The urgency to write what he had witnessed began with some scribbling in the camp, which he entered in 1944 and where he remained for the last nine months of its existence, and took greater shape immediately upon his return to Italy after Auschwitz was liberated in late January 1945. What worried him was the prospect of worldwide amnesia when it came to the annihilation of six million Jews. And he was largely correct, what with Holocaust denial invading universities and neo-Nazis goose-stepping around the globe only a few decades after his liberation. Just imagine if he were alive during the 2014 war in the Gaza Strip, when European protestors chanted: “Hamas, Hamas, Jews to the gas.”

Through , , short stories, novels, essays and poetry, this otherwise humble Italian chemist became an acclaimed writer and a universal symbol of the human rights movement. Unlike Elie Wiesel, however, who received a Nobel Peace Prize and whose own memoir, “Night,” landed him on “The Oprah Winfrey Show,” Levi remained largely unknown until decades after the war, except for Holocaust cognoscenti who regarded him, and still do, as having created the moral language for describing an atrocity as well as the clinical, emotionless testimony of how one recalls it.

While he had success in his native Italy, where he was regarded as a national treasure, it was not until the mid-1980s that several of Levi’s books were published around the world. (By that point, both Wiesel and Anne Frank were already household names.) And while Levi’s work received favorable reviews internationally, his books were not widely read. Much more of his writing remained untranslated, uncollected and unpublished.

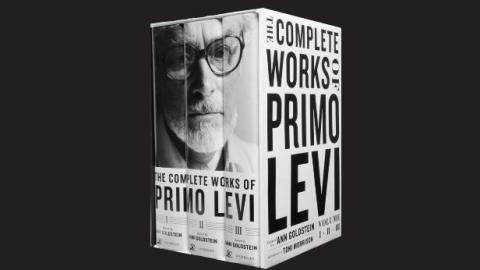

Until now. Liveright, an imprint of W.W. Norton & Company, under the direction of Robert Weil and edited by Ann Goldstein, has produced “The Complete Works of Primo Levi,” a handsome, monumental literary undertaking and a work of truly global significance. One of the 20th century’s most singular writers, a chemist who worked magic in turning testimony into art, and whose books conveyed the dark side and gray zones of the human experience like no other, may now, finally, receive a more complete reading and engage an entirely new readership.

Levi’s trilogy of memoirs — “If This Is a Man” (better known in the United States as “Survival in Auschwitz”), “The Truce” (similarly retitled in the United States, “The Reawakening”) and “The Periodic Table”— each a masterpiece in its own right, are now all gathered together, freshly retranslated and chronologically arranged alongside Levi’s poetry, commentary, science fiction, novels and his posthumously debated work of moral philosophy, “The Drowned and the Saved.”

While Levi was not solely a Holocaust writer and recoiled at being so ghettoized by critics and general readers alike, especially in the United States, one cannot help but recognize that even when he was reflecting on such diverse themes as technology, games, chemistry or even spiders, the different phases of his experience as a survivor of Auschwitz informed every word he ever wrote. How else could it be possible to convert the elements of the periodic table into reflections on the meaning of life, drawn from the world’s greatest experiment in human death?

This was especially true of his poetry, which was much darker and apocalyptic than his more hopeful, humanistic writings. Indeed, Levi reserved his mournfulness for his verse, which stands apart from his Holocaust (“If This Is a Man”) and post-Holocaust (“The Truce”) memoirs, where he exhibited a subdued style that became his trademark — a mixture of fine precision and emotional detachment. Reading Levi’s memoirs can often feel as if a scientist is at work conducting his own experiment, placing himself under the microscope of Auschwitz. He presents his findings with exactitude and suppresses his feelings with equal attentiveness. There is no rage, no calls for revenge. There is scarcely an admission that he has been damaged at all.

Paradoxically, throughout his Holocaust writings Levi acknowledges the impossibility, in its indescribableness, of his entire literary endeavor. After all, ordinary words fail to accurately convey what he witnessed. Language does not yet exist to transport readers to the scenes of such extraordinary, otherworldly crimes. The inhuman conditions of the camps were incomparable — all similes and metaphors, therefore, were stripped of their rhetorical power. And, yet, he continued to write — meticulously, economically and faithfully — despite his doubts that he could be understood. His determination to bear witness remained in perpetual conflict with the narrative limitations of the unspeakable crime he felt duty-bound to report.

And there are further mysteries to Levi, the writer-witness, that can only be attributed to the grotesque chemical agents, and corrupted moral agency, he observed in Auschwitz. One comes away with the improbable impression that he was a life-affirming optimist.Yet how is that to be reconciled with the tragic truth that he ultimately took his own life in 1987, shortly before the publication of the American edition of “The Drowned and the Saved”?

Levi was not alone in such a dramatic act of self-expression, apart from his writings. (He left no suicide note.) Indeed, almost all of the well-known Holocaust survivors who became writers committed suicide: Jerzy Kosinski, Paul Celan, Tadeusz Borowski, Piotr Rawicz, Bruno Bettelheim and Jean Amery. (None of them left suicide notes, either.) Ironically, Levi devoted two separate discussions, which appear in this collection, to Amery; one of them directly confronts his suicide.

Mercifully, Wiesel, along with the Israeli novelist Aharon Appelfeld and the Hungarian novelist Imre Kertesz, are outliers among this group of Holocaust writers who, in choosing to continually write about their wartime nightmares, never fully awoke from them. What made those who lived on different is mere speculation: Wiesel enjoyed the distractions of being a cultural rock star; Appelfeld became an Israeli, a nation with its own rituals regarding the Holocaust and Kertesz lived for many years in communist Hungary, which offered deprivations of a different sort.

Levi’s end was, perhaps, like the other Western Holocaust writers, tragically predictable. Through the solitary art of bearing witness, Levi dared to ask whether the wretched man who had returned to Turin was still, nonetheless, a man worthy of survival, a person entitled to a life renewed. Levi bore the burden of the survivor’s task of remembrance with more normalcy than should have been expected. He may have been born in Italy, but Auschwitz forever deprived him of becoming a fun-loving Italian. He would be granted no immunity to the trauma that lingers within the minds of those who chose to testify too thoroughly to what happened there.

Of course, Levi never shied away from examining all moral contours of the Holocaust. In “The Drowned and the Saved,” his last and most controversial work, he explored what he called the “gray zone”— the space that exists between the victims and the executioners, that ill-defined area where moral judgments are more difficult to render. Levi bravely suggested that not all victims were blameless — indeed, some were collaborators — and that not all torturers were monsters. Decades after Auschwitz, Levi sought to introduce more complexity and nuance to the moral categories that surrounded the surreal atmosphere of the Nazi killing machines.

Such subtle distinctions are dangerous, however, and largely unwelcome, when there is so much already invested in assigning fixed categories of good versus evil. Levi speaks of the “shame” and guilt that survivors naturally harbored, knowing that their survival so often depended on harsh moral compromises made at the expense of others whose lives ended at Auschwitz. He writes, “Those who were ‘saved’ in the camps were not the best of us, the ones predestined to do good. ... Those who survived were the worst. ... [t]he best all died.”

Literary critics and human rights activists adored Levi, but such pronouncements — judging the survivors as “the worst” simply because they survived — did not endear him to the community whose suffering he shared. Here was a secular Jew, a man who felt more Italian than Jewish and who managed to return to his mother and sister in his ancestral home in Turin, asking the remnants of European Jewry, many of whom were religious and suffered losses far worse than his own, to take account of their complicity in their own destruction.

And why stop with European Jews? Several years earlier, in 1982, Levi addressed himself in essays and public pronouncements to the political situation in Israel. Shortly after Israel invaded Lebanon to root out Yasser Arafat’s PLO, Levi lamented that Israel was becoming “less and less the Holy Land, [and] more and more the military state” with its damaged global image and weakened solidarity among European countries. Sound familiar? He even went so far as to acknowledge why some had unfavorably compared Menachem Begin with Nazi generals, and called for the resignation of Begin and Ariel Sharon.

In those days, far fewer Diaspora writers, especially novelists and poets, had involved themselves in the messy politics of the Middle East. And American Jews wondered why an Auschwitz survivor from a small town in Italy had anointed himself as a prophetic voice laying low Israel’s vaunted moral high ground. A message was sent across the Atlantic and the Mediterranean: Stick to crematoria, Primo, and leave the dirty work of counterterrorism to the sabras.

With the world in chaos and moral clarity in short supply, a thorough reading of Primo Levi might not prove to be an antidote for the present malaise. There are no happy endings when it comes to the Holocaust, and present-day madmen are loathe to draw any lessons from the great works of world literature. But there is, nonetheless, much that Levi had to say, in a style that was very much his own. And even if it doesn’t lead to a better world, this new collection of the entirety of his works could not have come at a better time.

Thane Rosenbaum

Thane Rosenbaum, author of “The Golems of Gotham” and, most recently, “How Sweet It Is!” is a Distinguished Fellow at the NYU School of Law and the director of the Forum on Law, Culture & Society.