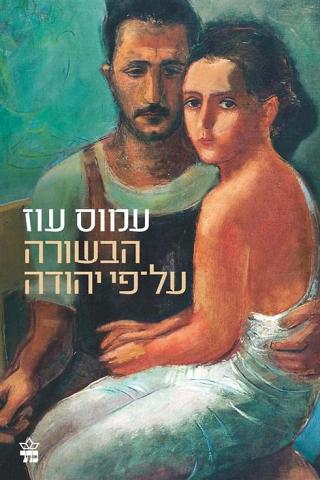

'Judas': Amos Oz's New Book

Could betrayal be a form of loyalty? Consider the archetype of betrayal, Judas, whom Dante consigned to the innermost ring of the Inferno. In 1937, after recovering from a stroke, the celebrated Hebrew writer A. A. Kabak published “The Narrow Path,” a fictional retelling of the life of Jesus. At the end of the novel, Jesus asks his disciple Yehuda Ish-Keriot (Judas Iscariot) to hand him over to the Roman oppressors in order to set in motion the uprising against them. Jesus recognizes that Judas alone is strong enough to fulfill the horrible demand. Knowing full well that he will enter history reviled as the man who betrayed the savior, Judas renounces his reputation, faithfully sells out his beloved teacher for 30 pieces of silver and becomes the first Christian martyr. It is his last and highest act of service to the divine plan.

In a critical review, literary critic Joseph Klausner, himself a scholar of Jesus, took Kabak’s historical novel as a misguided comment on the present. Klausner admired Kabak’s portrayal of Judas but took issue with his depiction of Jesus as a teacher who renounces violent resistance and prods his flock not toward national redemption but toward individual spiritual transformation. “The true freedom is not outside of us,” Kabak had his Jesus preach, “but within us.” Such a Jesus, Klausner claims, can be no model for the urgent tasks of contemporary Jewish nationalism. In “Judas,” his first novel in more than a decade, Klausner’s great-nephew Amos Oz artfully resumes the debate and reconsiders the contemporary meaning of Judas for the Jewish state.

Oz’s novel – a coming-of-age story about both a young man and a young country – is set in the winter of 1959. The euphoria of Israel’s independence has faded. Three people of three generations are closed up in a melancholy stone house on the western edge of Jerusalem, as if defying the encroachments of the collective drama on private experience. With an infallible ear for the acoustics of the house and the resonances of the divided city, Oz listens in to the fugue of their impassioned conversations.

Shmuel Ash is a pensive 25-year-old with betrayal on the mind. His grandfather, who came to Jerusalem from Riga, had been branded a traitor for serving in the British Mandate police. Shmuel, a graduate student and café revolutionary, believes that Stalin betrayed the revolution. As if in reply, Stalin appears to Shmuel in a dream and calls him Judas. As the novel opens, Shmuel’s six-member socialist group has split into two factions, his girlfriend has left him for another man, his father has gone bankrupt, and against the advice of his family, he has dropped out of Hebrew University, where he was studying Jewish views of Jesus. Shmuel insists he is an atheist, but – like Oz – he fell in love with the poignant beauty of Jesus’s parables while reading the Gospels as a teenager. In the eyes of his parents, Shmuel commits a double betrayal: first, by choosing to study New Testament figures, and second, by giving up his studies.

Himself powerless, Shmuel reflects a great deal not only on betrayal, but also on power. In what amounts to his credo, and perhaps his author’s, he describes the Jews as "a people that for thousands of years has known well the power of books, the power of prayers, the power of the commandments, the power of scholarship, the power of religious devotion, the power of trade, and the power of being an intermediary, but that only knew the power of power itself in the form of blows on its back. And now it finds itself holding a heavy cudgel. Tanks, cannons, jet planes…. Power has the power to prevent our annihilation for the time being…. It can’t settle anything and it can’t solve anything. It can only stave off disaster for a while." To stave off the effects of his own disasters, Shmuel takes a job as live-in companion and conversational sparring partner to a garrulous and opinionated retired history teacher, a 70-year-old invalid named Gershom Wald. In exchange for an attic room under a sloped ceiling of peeling plaster, Shmuel keeps Wald company every night from 5 until 11 P.M.

Shmuel’s attentions, however, are enthralled by the third member of the household, Atalia Abravanel, a beautiful but inaccessible woman in her mid-forties. Shmuel learns that she is a war widow; she had been married for less than two years to Wald’s only son, who died fighting on the road to besieged Jerusalem during the War of Independence. Amos Oz, born in Jerusalem in 1939, once wrote that he loves his native city “as one loves a disdainful woman.” Thus Shmuel loves Atalia. She remains beyond his reach. Self-assured but emotionally injured, Atalia has shut herself away in a shell of self-sufficiency and repressed sensuality. She treats Shmuel with faint mockery and aloof irony. As it progresses, “Judas” turns out to be not a trio but a quartet. Shmuel discovers that the walls of the house echo as much with the voices of the dead as of the living. Shmuel might be the hired help, but Wald’s true conversation partner remains Atalia’s late father, an idealistic member of the Zionist Executive Committee and Council of the Jewish Agency who believed that the scourge of nationalism would vanish. “Why do you need to rush to set up another Lilliputian statelet here, with blood and fire, at the cost of perpetual war, when soon all states are going to vanish?” (Wald, for his part, does not see why Israel should be the first country to divest itself of the sin of nationalism.)

Shealtiel Abravanel’s somber voice sounds a counter-melody to Wald’s. “The founding fathers of Zionism deliberately exploited the age-old religious and messianic energies of the Jewish masses,” Shealtiel hectors, “and enlisted them in the service of a political movement that was fundamentally secular, pragmatic and modern.” Where Wald argues that “the Jewish people has never before had such a far-sighted leader as Ben-Gurion,” Abravanel considered it a tragedy that Ben-Gurion – “a false messiah” – had abandoned the socialism of his youth. Abravanel “tried in vain to persuade Ben-Gurion in ’48 that it was still possible to reach an agreement with the Arabs about the departure of the British and the creation of a single joint condominium of Jews and Arabs, if only we agreed to renounce the idea of a Jewish state.” For this his neighbors called him an “Arab lover,” newspapers mocked him as “Sheikh Abravanel” and his colleagues forced him to resign from his leadership posts. He died ostracized and alone in this house on the edge of Jerusalem.

After three months, fearing he might rot between memories of the young woman who left him and unrequited fantasies of Atalia, Shmuel emerges from his uneasy hibernation. He resolves to leave both the house and Jerusalem, a city “which was always shrinking into itself as though waiting for some blow to fall at any moment.” On his way to the Negev, Shmuel arrives at a crossroads and encounters a solitary fig tree, perhaps the same one Jesus had cursed for its barrenness (Mark 11:13), and perhaps the same from which Judas, self-condemned, had hanged himself after the crucifixion. Irresolute to the end, Shmuel plucks a leaf from its branches and wonders where to go next; he was and remains a man adrift. At the close of this polyphonic story, Amos Oz’s reader is too left wondering: In whose voice are we meant to catch the tones of treachery? Who is the true traitor?

Shealtiel Abravanel was maligned as a traitor for breaking ranks with his Zionist colleagues, for his dreams of reconciliation and of the obsolescence of nationalism. Shealtiel’s nemesis, Ben-Gurion, was shunned for agreeing to the Partition Plan. So, for that matter, was Amos Oz, a founder of Peace Now and among the earliest to condemn the occupation of the territories Israel conquered in 1967 and to call for the creation of a Palestinian state. Is the traitor the apostle from the town of Kerioth? As “the author, the impresario, the stage manager, and the director of the spectacle of the crucifixion,” Judas is for Shmuel not the archetypal betrayer but “the most loyal and devoted” of the 12 disciples, Jesus’ closest confidante who alone saw with terrible lucidity what must be done. “Had it not been for Judas,” Shmuel suggests, as Kabak had suggested, “there might not have been a crucifixion, and had there been no crucifixion, there would have been no Christianity.” This esoteric view echoes a second-century Gnostic “Gospel of Judas,” discovered in Egypt. By betraying Jesus, Judas immortalized him.

Perhaps, Shmuel says, the taint of treachery attaches instead to the master who betrayed his disciple by remaining nailed to the cross instead of coming down to reveal himself and redeem the world. Or perhaps, Wald muses, in the largest and most lethal sense, one that so long pervaded Christian Europe, every Jew is a Judas. The apostle John called Judas the Son of Perdition, and St. Jerome in turn called Jews “the sons of Judas” who “take their name, not from that Judah who was a holy man, but from the betrayer.” Closer to our day, as Klausner and others wished to reclaim Jesus as a Jew, to embrace the rabbi from Nazareth as “flesh of our flesh,” brasher voices relentlessly identified the Jews with Judas. The literary critic George Steiner calls the “final solution” enacted by the Nazis “the perfectly logical, axiomatic conclusion to the Judas-identification of the Jew.” Susan Gubar, author of “Judas: A Biography,” goes so far as to call Judas the “muse of the Holocaust.” Oz gives Gershom Wald the last word. “In the deepest recesses of the Jew-hater’s imagination,” Wald says, “we are all Judas. Even 80 generations later we are still Judas.”

In the end, Amos Oz’s sonorous masterpiece resists harmonic equilibrium. “Judas” derives its power not from narrative action but from the din of its dialogue – alive with ambivalence, dense with quandaries that link private predicaments to the public dilemmas of our time. Chief among them: When might a betrayal of what one loves take the form of devotion to a higher loyalty?

Benjamin Balint