The Human Brainome Project

Reporting April 3 in Nature, researchers at the National Institute on Drug Abuse in Baltimore and the University of California, San Francisco used optogenetics to produce or diminish compulsive cocaine use in rats by manipulating the activity of a specific group of neurons.

Researchers hope the findings lead to new therapies for drug addiction, but the road to clinical application is a difficult one and requires a sustained investment. “The evolution of optogenetics or similar techniques needs a lot of help, because the benefits are going to far, far outweigh the costs,” says coauthor Antonello Bonci of NIDA.

A huge advantage of optogenetics, he says, is that it can manipulate neurons almost in real time. But it can’t be used for long periods. In his lab, Bonci complements optogenetics with another promising technique that has lower time resolution but can be used for longer. It involves implanting neurons engineered to respond to certain compounds. Injecting those compounds can activate or silence the cells.

Preparing for the data flood

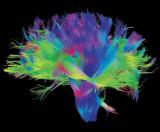

Monitoring and manipulating individual cells is only part of the challenge; tracking a million neurons a thousand times a second will produce a lot of data. Software, databases and hardware will be needed to store and distribute that information, and to process and analyze it. Project proponents met at Caltech in January to discuss how to address the data needs — roughly a gigabyte a second for a million neurons simultaneously, or 30 million gigabytes a year.

Researchers could compress the data by a factor of 10 without sacrificing crucial details, according to a report from the meeting. Ultimately, the data problem shouldn’t be insurmountable, Yuste says. Another proposed big science project, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, would produce around 10 million gigabytes of astronomical data annually starting in the early 2020s — right when million-neuron tools could come online, he notes.

Technical obstacles aren’t the only worry Yuste and his colleagues have. The recurring state of fiscal crisis in Washington makes it difficult to get any big project off the ground. Uncertainty over funding has fueled skepticism among scientists, who wonder whether money would be taken from other research to fund a “Big Science” project that lacks a concrete final goal.

National Institutes of Health Director Francis Collins notes that his agency has formed a workgroup of neuroscientists and some nanoscientists — supportive and skeptical alike — to guide the project’s timetable and scientific goals. One of the cochairs is Cori Bargmann, a Rockefeller University neuroscientist who previously raised concerns that the project could take funding from other neuroscience work.

Gary Marcus, a neuroscientist at New York University, says he is concerned that the project focuses too much on tool development, but notes that the administration’s proposal may be flexible enough to fund projects in other areas of neuroscience. He fears what will happen if the tools are developed but don’t yield all the promised insights. “We will surely learn something,” Marcus says. “Whether we learn everything we want to know is another question.”

By Puneet Kollipara