The Holocaust: It Wasn't Just About Jews

Breaking the taboo would entail coping with a different collective memory, as well as recognizing that Nazism was much more than the enemy of Jews alone – that it was the enemy of all humanity. In addition to the Jews, the Nazis murdered millions of other people only because they belonged to a group that Nazism decreed unworthy of existing. Each such group has its own distinctive story. And the tragedy of each deserves to be remembered as part of a broad mosaic of memory in which an equal place is accorded to all the victims of Nazism and to the victims of other genocides.

The modest book edited by Yair Auron and Sarit Zaibert tries to fulfill this mission, which is of crucial historical importance, but primarily conveys a crucial humane message. It’s an almost impossible mission in the violent, racist, proto-fascist Israel of 2016. The character of the book’s articles and some of its source materials suggest that it is intended mainly for high-school students or for the general reader who wants to broaden his knowledge of a subject on which almost no material exists in Hebrew. And although the editors’ initiative is welcome, the result is disappointing, even sloppy.

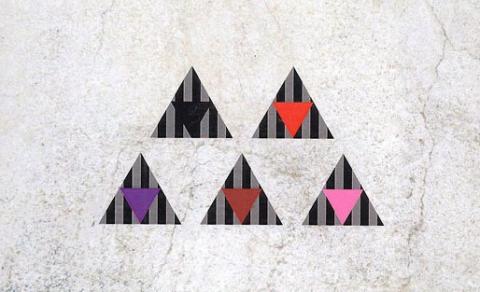

The collection consists of a number of articles about non-Jewish victims of Nazism: Gypsies, Jehovah’s Witnesses, euthanasia victims, homosexuals and other prisoners in concentration camps. There is also a general piece about the policy of racial enhancement pursued by Nazi Germany. In addition, various source materials are appended to the articles, though they do not share a common denominator. They consist of testimonies and memoirs, excerpts from Gunter Grass’ autobiography “Peeling the Onion,” literary passages, a section from a play dealing with homosexuals in the camps, passages about memorial sites and others.

If the aim were to make accessible material that speaks to young people, the editors would have been better advised to devote time and effort to including primary testimonies of survivors from the various groups of victims covered in the book. Numerous testimonies of this kind are available today, with the exception of the ill-fated unfortunates who were murdered in the euthanasia program, of which there were of course no survivors. Even in the case of homosexuals – a group whose fate was not investigated for many years, because of the survivors’ reluctance to have their stories made public – far more important primary material is available now than is provided in the book.

The historical surveys that form the collection’s backbone are not of uniform quality. In contrast to several articles that offer an orderly, proper explanation of their subject, such as Moshe Zimmerman’s article on homosexuals and on the so-called “asocial” elements, and Nira Feldman’s on euthanasia victims, the other articles are superficial or not up-to-date and even mistaken in the interpretation they offer.

An example is Yehuda Bauer’s article on the Gypsies. Undoubtedly an acclaimed Holocaust researcher, Bauer’s scholarly work is not identified with the Gypsy genocide. His contribution here is the abstract or summary of an article he wrote a while ago on the subject. Important studies on the subject have been written since then by German and American researchers, and these should have been cited. Indeed, the Gypsies should have received more thorough treatment in the book, as they are an ethnic group whose persecution and murder derived from the same racist worldview that underlay the persecution and murder of the Jews.

Even more puzzling is the survey by historian Gideon Greif of the prisoners of the concentration camps in the initial period, up to the outbreak of World War II in 1939. The declared aim of the book under review is to deal with non-Jewish victims of Nazism. Yet Greif tries by every means possible to include the Jews – a small and not particularly central group among the camps’ inmates until the “November pogrom” in 1938 – and even then, only for a brief period. No mention is made of the fact, for example, that the network of camps was not created or intended to serve Nazism’s anti-Jewish policy in the 1930s.

At several points Greif almost apologizes about the fact that there were no Jews among the prisoners who were sent to the camps before the outbreak of the war. The reason was that they were not categorized as political opponents subject to persecution, or that no Jews fit the vague definition of “asocial” people. Yet when Greif does present a personal testimony, it is that of a Jewish inmate.

Commonplace mistakes also appear in Greif’s unconvincing survey. For example, he maintains that there was no law in the camps and that the Nazis’ violence was arbitrary and was administered according to unwritten rules laid down by the S.S. In fact, this was the period in which the operations at the concentration camps were shaped by their first commandant, Theodor Eicke. The code of management of the concentration camps that Eicke drew up was a binding document, and the rules it set forth were obeyed by his underlings. This is not to say that the inmates did not suffer from violence, but it cannot be termed arbitrary violence, as this is precisely what Eicke sought to prevent.

Another highly problematic article is that by scholar Isaac Lubelsky on racism and racial enhancement in Nazi Germany. Lubelsky begins with a hasty survey of the development of the concept of Social Darwinism in the 19th century and its influence on Hitler’s modes of thought. He then proposes that the evolutionary idea, which sees a connection between the environmental existence of a specific human group and its mental, cognitive and physiological development, was prevalent not only among thinkers and scientists during the era of racism in the 20th century, but was also accepted by many good people who could not be suspected of harboring racist tendencies. For example, the poet Shaul Tchernichovsky, who wrote that “man is molded by the landscape of his homeland.”

In fact, if we adopt the interpretation accorded this poetic work by the literary scholar Dan Miron, the exact opposite is the case. The idea here, Miron explains, is that man is made of a certain model, scheme, paradigm that assumes a concrete dimension in the mold of the landscape of his homeland. In other words, the materials of which a person is made create the mold of the landscape of his homeland – and not the other way around. The influence of Social Darwinism here is not readily apparent.

These are only a few examples of the problems that mark this book. Important groups of victims are absent altogether. Among them are Soviet prisoners of war, the second-largest group of victims (more than three million) annihilated by the Nazis. Also missing are the Poles, who underwent a combined onslaught of ethnic cleansing and mass murder.

In short, the book constitutes a missed opportunity. A serious collection of articles in Hebrew about non-Jewish victims of the Nazi genocide would be of vast importance. If this initial unfortunate attempt spurs an initiative to publish such a volume, the book will have served its purpose.

Daniel Blatman