GMOs and Engineered Food

The Situation

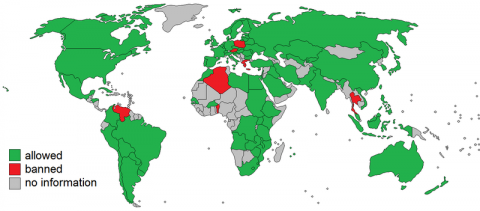

Two decades after engineered crops were first sold to Americans, President Barack Obama in late July signed into law a national requirement that engineered ingredients be disclosed on food packages. The rule overrides state laws, like the one that took effect in Vermont July 1. It requires food manufacturers to disclose the presence of GMOs on the package using text, a symbol or a code to be scanned with a smart phone. Critics have assailed the latter option as discriminatory to the elderly and poor who are less likely to have such a phone. More than 60 countries have labeling requirements, including Japan, Brazil, China and the entire European Union. The biggest developers of GMOs also sell most of the world's commercial seeds. They are led by Monsanto, which has a 27 percent market share and agreed to be acquired by Bayer in September. Dow Chemical and DuPont, which plan to merge, together have 23 percent of the seed market. Syngenta, which agreed to be acquired by ChemChina, has 8 percent.

The Background

Humans have been manipulating crop genetics for thousands of years, crossing and selecting plants that exhibit desirable traits. In the last century, breeders exposed crops to radiation and chemicals that induced random mutations. These and other lab methods gave fruits and vegetables new colors, made crops disease resistant and made grains easier to harvest. Most wheat, rice and barley are descendants of mutant varieties, as are many vegetables and fruits. Hello, Star Ruby grapefruit! In the early 1980s, scientists discovered how to insert genes from other species into plants. The process led to the 1994 commercialization of the first GMO, the FlavrSavr tomato. It was weak tasting and was pulled from the market. In 2015, the first GMO meat was approved for sale in the U.S. AquaBounty Technologies’ salmon engineered to grow twice as fast as conventional salmon, with less feed, awaits GMO labeling guidelines before it can be imported from inland fish farms in Canada and Panama for sale in the U.S. Mosquitoes engineered to bear non-viable offspring have the potential to combat human diseases such as dengue fever and the Zika virus without chemical insecticides.

The Argument

GMO supporters point to a scientific consensus reflected in reports and statements from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, the American Medical Association and even the European Commission, that GMOs pose no more risk than other crops. Nor is there doubt that they’ve cut insecticide use, reduced soil erosion, made farmers more efficient, and even saved Hawaiian papayas. Consumers remain leery nonetheless, not only of GMOs themselves but of their central place in industrial agriculture. Anti-corporate ideology plays a role, with Monsanto emerging as a bogeyman in popular culture. Weeds and pests targeted by engineered crops are genetically adapting themselves, with dismaying implications: Monsanto’s bug-killing corn is so widely used that the corn rootworm is developing resistance, requiring the use of more pesticides after years of decline. The food industry is divided. The Grocery Manufacturers Association and supporters spent $68 million on campaign advertising to defeat labeling referendums in California and Washington. The organic food industry, which has quadrupled its annual sales since 1999 to $80 billion globally, is a prime financial supporter of labeling efforts, anticipating more growth from frightened shoppers.

The Reference Shelf

• The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine published a research review on the safety of genetically modified crops.

• The Department of Agriculture in February 2014 published a report on the status of GMOs in the U.S.

• The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-Biotech Applications maintains a database of GMOs approved around the world.

Jack Kaskey