Fixing Fragile Cities

Another factor that stokes crime and insecurity is rapid urbanization. Urban geographers have found that the size and density of cities do not predict criminality. After all, Seoul, Shanghai, and Tokyo are among the largest cities in the world, but they are also among the safest. Rather, the key factor appears to be the breakneck pace and unregulated nature of urban growth, or turbo-urbanization.

Karachi stands out in this regard. This Pakistani behemoth swelled from roughly 500,000 inhabitants in 1947 to more than 21 million today. And although it now generates more than three-quarters of the country’s GDP, the megapolis has become one of the most violent in the world. A number of other fragile cities—including Dhaka, Kinshasa, and Lagos—are now 40 times larger than they were in the 1950s and similarly dangerous.

Demographers also detected a tight relationship between the concentration of young people and the level of violence. Many low- and middle-income cities have outsized youth populations. In some of the most fragile ones, 75 percent of the population is under the age of 30. The mean age of urban residents in Bamako, Kabul, Kampala, and Mogadishu, to name just a few, hovers at around 16. By contrast, the average age of city dwellers in Berlin, Rome, and Vienna is 45.

It is not just youthfulness that predicts city fragility, however, but the specific characteristics of the young population. Those who are unemployed, undereducated, and male face a greater risk of being killed or becoming killers themselves. According to some epidemiologists, there is a contagious dynamic to violence between these kinds of people. The reverse is also true: the presence of well-educated and employed young residents—the so-called creative classes—in a given neighborhood brings numerous positive dividends, including public safety.

URBAN RENAISSANCE

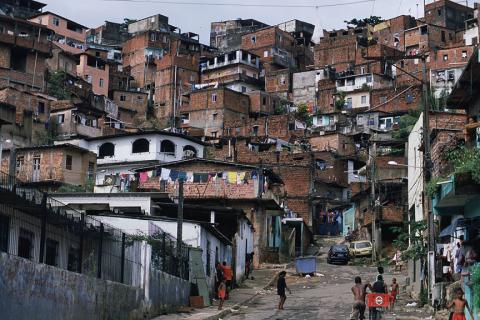

The good news is that city fragility is not immutable; it can be reversed with time and investment. Take Rio de Janeiro, once considered a paradigmatic city on the edge. Its gang and police violence in the 1990s and early 2000s had become legendary, and residents of its densely populated low-income neighborhoods, known as favelas, have grown accustomed to the boom and crackle of gunfire.

But from 2009 on, Rio de Janeiro has experienced a remarkable transformation. Homicide rates fell precipitously—declining by 65 percent between 2009 and 2012. Investment has started flowing back in. Residents and tourists are returning. Although problems remain and violence is still unacceptably high, the city is recovering, thanks to its leaders’ new approaches to policing and social investment.

Rio de Janeiro is not the only megacity to have staged a comeback. Neighboring São Paulo, too, went from being one of Brazil’s most dangerous urban centers to one of its safest, as its homicide rate plummeted by 70 percent between 2000 and 2010. Other case studies of successful turnarounds include Mexico’s Ciudad Juárez, Colombia’s Medellín, and even New York—all of them witnessing significant declines in lethal violence over the past few decades.

Additional examples abound. Even cities showing some symptoms of extreme fragility—such as Johannesburg, Kingston, Lagos, Nairobi, and San Salvador—have achieved remarkable improvements. And histories of more definitive turnarounds, particularly in North and South America, suggest that a combination of measures can stem fragility if policymakers commit to seeing them through.

The first step is improved communication. In some places, mayors have opened a lively dialogue with vulnerable communities about gang violence and factors that drive it such as extreme income inequality, inadequate service provision, and weak or corrupt police and justice institutions. This kind of honest dialogue is essential for identifying shared priorities and deploying scarce resources most efficiently. Mayors such as Enrique Peñalosa in Bogotá, Rodrigo Guerrero in Cali, and Antonio Villaraigosa in Los Angeles have all shown that a radical change of approach is possible.

Another solution is bringing fragile cities together with healthier and wealthier ones to share experience. As early as the 1950s, twinning initiatives of this kind partnered North American cities with war-damaged European ones to aid with reconstruction. More recent initiatives partnered U.S. cities with African ones, Australian cities with cities in the South Pacific islands, and Canadian cities with Latin American municipalities. Large foundations are also getting into the act by contributing to initiatives that enable the world’s municipal leaders to share ideas (such as the New Cities Foundation and the United Cities and Local Governments network) and tackle broader international challenges (as the fledgling Global Parliament of Mayors intends to do).

Yet another option is to focus on hot spots by predicting and, where possible, preventing violence. Policing such hot spots produces positive effects for entire neighborhoods, with considerable evidence that adjacent communities also benefit. But developing an effective approaches requires investing in real-time data collection and problem-oriented law enforcement. It also requires new technologies, such as the data-driven police management and surveillance tools adopted in the United States, known as Compstat and Domain Awareness Systems. Given that such approaches rely on surveillance, including smart cameras and license plate readers, they have sparked justified concerns about personal privacy. But these concerns are counterbalanced by the benefits that new technology—including predictive analytics, remote sensing, and body cameras worn by police—offers to law enforcement.

Strengthening cities requires greater attention not just to specific spaces, but also to specific groups of people. Young unemployed men with a criminal record are statistically more likely to violate the law than other residents who have not committed crimes. Indeed, only about 0.5 percent of people generally account for up to 75 percent of homicidal violence in major cities. But instead of locking up and stigmatizing young men, municipal officials should support them. Proven remedies include mediation to interrupt violence between rival gangs, targeted education and recreation projects for at-risk teenagers, and counseling and childcare support for single-parent households.

The most far-reaching and sustainable strategy for strengthening fragile cities involves purposeful investment in measures to boost social cohesion and mobility. City planners and private investors must avoid the temptation to reproduce segregation and social exclusion, and they must insist that the public good prevails over private interests. Investments in reliable public transportation, inclusive public spaces, and pro-poor social policies (such as conditional cash transfers) can go a long way toward improving safety.

There are many examples of how to drive down crime, but Medellín provides the most convincing case of how to do it best. During the 1990s, Medellín was the murder capital of the world. But a succession of mayors beginning with Sergio Fajardo turned things around by focusing their attention on the poorest and most dangerous neighborhoods. They connected the city’s slums to middle-class areas by a network of cable cars, bus transport systems, and first-class infrastructure. By 2011 homicidal violence declined by about 80 percent, and in 2012, Medellín was named the city of the year (beating out New York and Tel Aviv) in an annual competition held by Citi and the The Wall Street Journal.

There are hopeful signs that new technologies can play a decisive role, too. Internet penetration and information communication technologies are already closing the digital divide between and within urban centers. New smart cities that have begun to take advantage of these tools include Tanzania’s Kigamboni (an administrative ward of the capital Dar es Salaam), Congo’s Cité le Fleuve, Kenya’s Tatu and Kozo Tech, and Ghana’s Hope and Eko cities. And in India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently announced plans to create 100 smart cities over the next two decades, adding to India’s growing tally of tech-friendly urban centers such as Ahmedabad, Aurangabad, Khushkera, Kochi, Manesar, Ponneri and Tumkur. Investments in hard and soft technologies are fueling a virtuous cycle by supplying cities with yet more new talent and consolidating their place as hubs of innovation and connectivity.

To turn fragile cities around, public authorities, businesses, and civic groups must come to grips with the risks that will come with rapid urbanization but also with the many available solutions. This means starting a conversation about what works and what doesn’t and sharing these findings globally. Successful mayors in developing countries will need to use lessons learned around the world to solve local problems. The more proactive among them are already doing so.

Robert Muggah