A child's view of the crumbling Soviet empire

In the school’s cocoon of communal living, Kat is thrown into the social kaleidoscope of the typical Soviet classroom: the child of the party functionary, the Jew, the Georgian, the Ukrainian, the mixed-blooded-Tatar. Typical challenges of boarding school life arise: the cruelty of other children, competition to succeed, favoritism of teachers, strange forms of physical therapy throughout the school day, childhood sweethearts and discotheque evenings. Children flaunt their parents’ political theories as they play in the schoolyard: “Slave mentality is a uniquely Russian quality... People in Russia are like dogs. The worse you treat them, the more they adore you.”

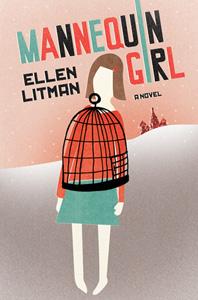

Desperate to move beyond her crooked spine and the pariahdom which Soviet medicine has imposed on her because of it, Kat looks for opportunities to excel and give her parents reason for pride -- she dreams of becoming an actress and memorizes plays endlessly, striving to break free of the stigmas attached to her condition, in a world where to be different is a criminal sentence. When the doctor reassures her that she has a beautiful figure regardless of her condition, that she is as perfect as “a mannequin girl,” she finds a brief window of hope -- only to find out later that every other girl is told the same.

Such is Kat’s adolescence, depicted against the backdrop of perestroika -- economic and political reform as the Soviet Iron Curtain began to fall: It is a portrait of disillusionment.

Bohemian childishness

As she grows older, Kat watches her parents on her weekly visits home. Eventually, as they are hired to teach at her school, she does so with the eyes of an old soul, noting their bohemian childishness, their unsettling flaws, their disintegrating marriage. Her dreams of becoming an actress soon dissipate, and her own personal ideals begin to weaken as the country around her does as well. With time, and with enough heartbreak, Kat begins to seek something else entirely -- neither stardom nor brilliance, but something ordinary, something “pedestrian.”

What is perhaps most striking about the novel is the secondary emphasis given to politics. Communism is a mere flavoring, coincidental as far as a young teenager is concerned, but a part of the culture that Litman -- a Moscow-born immigrant to the United States -- evokes effortlessly. The reader is thrown into the bleak reality that was the final years of the Soviet Union, a reality that reeks of cigarettes, potatoes and sausage, unwashed clothing, colorless sweaters and identical apartment blocs. And with Soviet anti-Semitism growing in the late 1980s, alongside the virulently nationalist organization Pamyat, the faintly Jewish touches are true to life: the collective obsessive science of analyzing secretly Jewish last names, the art of distinguishing Jewish faces and accents, the fight against common Russian belief that “Jews had sat out World War II.”

Cultural details are well-placed, included in the English prose without a beat being skipped: Alla Pugacheva’s pop music (“Kings can do anything except marry for love”) alongside classics like the Sevastopol Waltz and quotations from the beloved children’s cartoon “Cheburashka”. Even the seemingly untranslatable folk phrases (“Good luck and a road like a tablecloth”, “Devils live in still waters”), and poetry (Sergei Esenin’s “rakish” idling in Moscow), find a home in Litman’s tender English. Here, dissidence is still alive, though no longer novel, in the death of hoarse-voiced bard Vladimir Vysotzky, in the gleefully sung blatnie (banned) songs, in the samizdat literature that nearly every Jewish intelligentsia home harbored.

And it’s not just the poetry, or the music, that Litman uses as color -- it’s the small moments that are at once the most desolate and most telling, when the mere weather forecast breathes Soviet: “There’s always mild frost in Belarus. Sixteen to twenty-one degrees in Georgia. Slight rain in Leningrad. Westerly winds in Moscow. So familiar. So imprecise.”

Litman has created a refreshing and memorable heroine in Kat, a voice that is clever, perceptive and well-developed -- significantly more developed than the characters of her last work, a series of related short stories, “The Last Chicken in America.”

“Mannequin Girl” is indeed a story of the ordinary, the “pedestrian” and unredeemed; not the heroic saga of Soviet Jewry but rather a window into the everyday life of the non-refusenik, the non-Zionist, the non-immigrant who may very likely choose to stay in Moscow. And perhaps here lies its importance -- in the stagnation of the world it depicts, in its sterile Moscow flats and its mundaneness, Litman has expertly painted a still life, a Soviet childhood in all of its rawness.

Avital Chizhik