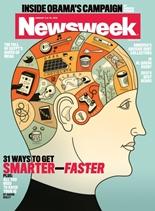

Buff Your Brain

As we dug into the latest research in neurobiology and cognitive science for this second annual installment of the Newsweek/Daily Beast guide to being smarter in the new year, one discovery from 2011 therefore stood out above all the others: that IQ, long thought to be largely unchangeable after early childhood, can in fact be raised. And not by a niggling point or two. According to a groundbreaking study published this fall in Nature, IQ can rise by a staggering 21 points over four years—or fall by 18.

A higher IQ can get you more than admission to Mensa and bragging rights on online-dating sites. IQ, measured by a battery of tests of working memory, spatial skills, and pattern recognition, among others, captures a wide range of cognitive skills, from spatial to verbal to analytical and beyond. Twenty points is “a huge difference,” says cognitive scientist Cathy Price of University College London, who led the research. “If an individual moved from an IQ of 110 to an IQ of 130 they’d go from being ‘average’ to ‘gifted.’ And if they moved from 104 to 84 they’d go from being high average to below average.” Her study was conducted on people ages 12 to 20, but given recent discoveries about the capacity of the brain to change—a property called neuroplasticity—and to create new neurons well into one’s 60s and 70s, Price believes the results hold for everyone. “My best guess is that performance on IQ tests could change meaningfully in adult years” too, she says. “The same degree of plasticity [as seen in young adults] may be present throughout life.”

In their recently published study, Price and her colleagues documented how IQ changes are linked to structural changes in the brain. In the 39 percent of subjects whose verbal IQ changed significantly, before-and-after brain scans showed a corresponding change in the density and volume of gray matter (the number of neurons) in a region of the left motor cortex that is activated by naming, reading, and speaking. In the 21 percent whose nonverbal IQ (any problem-solving unrelated to language, such as spatial reasoning) rose or fell, so did the density of gray matter in the anterior cerebellum, which is associated with moving the hand. Although most of us think of motor skills and cognitive skills as like oil and water, in fact a number of studies have found that refining your sensory-motor skills can bolster cognitive ones. No one knows exactly why, but it may be that the two brain systems are more interconnected than we realize. So learn to knit, or listen to classical music, or master juggling, and you might be raising your IQ.

Sharon Begley