The life and death of "the Jew Suess"

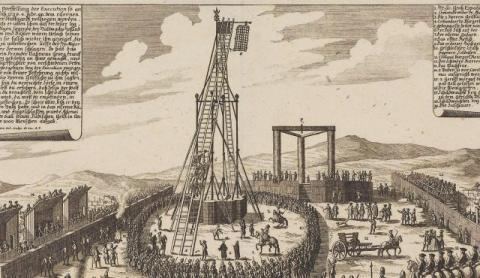

The duke’s protection was to Oppenheimer’s detriment. On March 12, 1737, Carl Alexander died of a sudden stroke, and that very evening Oppenheimer was placed under arrest. He spent the following 11 months in prison, first at the Hohenneuffen fortress south of Stuttgart, then at the Hohenasperg fortress north of the city and finally in the Herrenhaus in Stuttgart itself. Convicted of unspecified “misdeeds,” Oppenheimer was executed by hanging outside Stuttgart on February 4, 1738, before an audience of nearly 20,000 spectators. His body was left on display in a gibbet north of Stuttgart for six more years.

The death of “Jew Suess” quickly became the focus of hundreds of stories, poems and pamphlets. “The Story of the Passing of Joseph Suess, of Blessed Memory” stands apart from them all in that it is the only document we know of that was written by Jews, almost certainly on the instructions of Oppenheimer himself, on the eve of his execution. We thus have before us for the first time the story of Oppenheimer’s death as he himself would have wished to tell it, in utter contrast to the numerous contemporary sources that described the bitter end of “the sweet Jew” (the meaning of the name “Jew Suess” in German) from a very hostile point of view.

Although he was executed nearly 300 years ago, Oppenheimer’s trial never quite ended. Even as the legal proceedings were unfolding, it became clear that what was placed in the scales of justice were not his supposed crimes (no formal indictment was ever submitted against Oppenheimer, and the vague verdict failed to provide any details whatsoever about the reasons for his death sentence). The significance of the trial, and the reasons for the public tumult it provoked in German society, cannot be found in the dry language of legal treatises but in the role the story played as a parable about the rise and fall of prominent Jews in pre-modern and modern times.

Oppenheimer’s meteoric success during the years he spent in Stuttgart and his no-less spectacular fall in the aftermath of the death of his patron the duke have been viewed by many as a parable about the story of German Jewry both in Oppenheimer’s time and even more forcefully in the 19th and 20th centuries. At every point in time when the status, culture, past and future of Germany’s Jews were hanging in the balance, the story of this man moved to center stage, where it was investigated, novelized, set to music and even sung in a variety of forms. Early in the 19th century, it was the important novella by Wilhelm Hauff about Jew Suess. In the 1920s, the first comprehensive biography of Oppenheimer, by Selma Stern, was published, and in 1925, the significant historical novel by Lion Feuchtwanger. During World War II, there was Veit Harlan’s notorious anti-Semitic film.

If it was in fact Oppenheimer who wished to have the story of his death told as it appears in the document before us, then he himself was already aware of the symbolic and historical significance of his trial, and was consciously attempting to influence the way in which it would be remembered. The significance of the document before us does not end, therefore, with the details of the arrest, incarceration and execution, many of which are available to us from other sources as well. The principal significance of the document, rather, lies in what Oppenheimer himself was trying to achieve through it.

Who was the author of “The Story of the Passing of Joseph Suess, of Blessed Memory,” and when and where was it composed? Several contemporary German sources refer to the existence of a single-leaf pamphlet, written in Hebrew letters, copies of which arrived in Wuerttemberg no later than March 1738. These sources even identified the place of printing as the city of Fuerth (near Nuremberg). In three different instances, local scholars even decided to translate the text into German in order to show how the Jews were bestowing praise on the life and achievements of the “criminal” Oppenheimer, to the extent that they even termed him a saint.

For many years, these translations were the sole evidence of the existence of a “Jewish narrative” of Oppenheimer’s life and death, but the malicious language employed by their authors against the Jews, and the fact that from the time of their publication and for the nearly three centuries that ensued the original remained undiscovered, placed a large question mark over the historical veracity of the document.

We are indebted to Helmut Haasis for the reappearance of the original. Haasis, a German journalist, writer and historian, devoted many years to writing a comprehensive biography of Oppenheimer. Several years ago, a private collector revealed the original document to Haasis, who rescued it and sent a copy of it to this author (Haasis does not read Hebrew). A comparison between the original and the 18th-century translations of it prove beyond doubt that this is the very same Jewish pamphlet, copies of which were seen in several locations in southwest Germany and translated into German in the weeks that followed Oppenheimer’s execution.

Finally, the question of authorship. The author does not identify himself other than to say that he was one of the two Jews who visited Oppenheimer in the Herrenhaus in Stuttgart on the eve of his execution (the other was Mordechai Schloss). The trial documents and contemporary accounts confirm that such an encounter took place, and make it even possible to identify the author of “Story of the Passing” as one Salomon (Zalman) Schechter, a ritual slaughterer by profession. Schechter wrote the story in a melange of German and Hebrew. If, as the author claims, Oppenheimer indeed instructed Schloss and Schechter “to write about how he died to all of the Jewish Diaspora,” then the intended audience of “The Story of the Passing of Joseph Suess, of Blessed Memory” includes you, the readers of these lines. Its publication in Haaretz qualifies as belated adherence to the request that Joseph Suess Oppenheimer himself made in his last will and testament, 275 years ago.

The Story of the Passing of Joseph Suess of Blessed Memory

"Be it known that there was a man in Stuttgart in the state of Wuerttemberg, who became ever greater in the stubbornness of his heart and his pride, in his wealth and his wisdom, and he was called Joseph Suess. This Suess became a high counselor to Duke Carl Alexander, and rose in importance with each passing day. One day, his master the duke passed away. That very night, Suess was arrested by dint of royal edict, was chained by ropes of iron and was placed for a duration of eleven months in Asperg, the great fortress, where he was surrounded by guards who were men of war.

"The life story of Suess is known far and wide, as are his actions against the almighty God and against human beings. But because the time of his judgment had arrived and the time of his departure from this world, we must first of all give public announcement to the whole world of his name, and ask that his name be read out in every Jewish community: The martyr Joseph Suess ben Issachar Suesskind Oppenheim of blessed memory, whose soul departed in sanctification of the Lord’s name, may his soul rest in paradise with the other righteous individuals and repentants forever and ever, amen and amen. And because he passed away in possession of a full belief in God, and wholeheartedly regretted the transgressions he had committed, neither we nor any members of the Jewish faith can ponder upon it until the arrival of the Messiah.

"Firstly, while Joseph Suess was imprisoned in the Asperg fortress, from Rosh Hashanah 1737 until the day of the trial, he subsisted solely on thin bread and water. "Secondly, he fasted each and every day, and only when evening fell did he eat something, and each week he fasted two or three entire days. Last Passover, he subsisted solely on bread, water and turnips. The reason for all this was revealed by the wholly righteous person prior to his death, and anyone of intelligence can understand his reasoning. And the way in which he acted within the prison is truly incredible.

"Finally, on Wednesday the ninth of Shevat 5498 (January 1737), Suess was transferred to the city of Stuttgart under the guard of 200 men of war with drawn sabers and loaded muskets, and a large assembly of people all around, beyond enumeration, as the sand which is upon the sea shore. Suess was placed in Stuttgart in the Herrenhaus in the market square, in a single room, where it is customary to imprison the criminals, with a guard of 20 men and several officers. This transfer alone, until he arrived at this room by way of the city, was tantamount to a first death. And on that day, he did not ask or demand any food or drink, except for a kettle of tea.

"On Friday, the eve of the holy Sabbath on which the Torah portion “Beshalah” is read, he was informed of the death sentence against him. Immediately, several priests entered his room, who attempted to effect an upheaval of his faith. And the sainted Joseph Suess of blessed memory immediately fell to his knees and with his arms raised high, said in these words, and with great import: Gentlemen, what you are perhaps thinking of asking me? I request that you spare me these words; withdraw, and go back to your homes. Because I am left without much time to become reconciled with my Lord, blessed be he and blessed be his name. Do not disturb my rest any longer. And that is what happened.

"Last Sunday, Joseph Suess asked for and received a Jewish prayer book and other books. These were the prayer book of Rabbi Michels, with prayers in great benevolence to the Blessed Be He, and a midnight tikkun [in Jewish liturgy, prayers of repentance], which contained an extensive confessional prayer. Following the prayer, Joseph Suess asked to see Rabbi Mordechai Schloss and other Israelites. This request of his was also granted to him by the authorities. And so, the aforementioned Rabbi Mordechai came to him, and as soon as he saw him, Joseph Suess fell upon the man’s neck, and cried and shouted a great deal, and immediately told this Rabbi Mordechai that the time was too short to engage in matters of this world. Rather, he had to think of the Blessed Be He and regret the transgressions he’d committed.

"Afterward, the two men spoke alone and I am forbidden from saying what they spoke. Verily, I do not have enough quills and ink to describe his passing from this world. What’s more, it is difficult for me due to my great sorrow. Nevertheless, it is true that the world has not seen such a saintly man as Suess for a very long time.

"Witnesses to his last will and testament were the secretary and other persons, as well as myself and Rabbi Mordechai Schloss and other lower-ranking officers, and all were present in the room and signed their names, and this will be to the greater honor of Suess. And the reason for this is that of all of the property of this saintly man, only the amount of 3,000 Reichsthalers remained, and of that sum he gave something to the priests, but the majority he gave for the benefit of Jewish communities for the sake of study of the Torah and so that they would light an eternal flame for him in his memory for a full year’s time. In short, I cannot describe everything, but neither did he forget his mother and his brother and brother-in-law.

"Suess remained in his full wits, and asked Rabbi Mordechai Schloss that following his death he write to all of the holy communities, asking them not to call his holy spirit reproachfully or refer to it in an evil connotation, God forbid, but to publicly announce that he died in sanctity of God’s name, may it be blessed, and that he was always fearful of additional deaths of members of the Jewish people, God forbid, but through God’s help, no such thing occurred. In any event, after this his soul departed, as he was calling ‘Hear O Israel, the Lord is God, the Lord is one.’ And 52 steps led to the gallows themselves, and as he climbed each one of them he said, the Lord is God.

"In conclusion, who would be able to recount his praises? And prior to his death the saintly righteous man Joseph Suess of blessed memory instructed, in a true and full heart, to write about how he died to all of the Jewish Diaspora and to caution against arrogance, and that the Blessed be he will with God’s help keep all of Israel alive until the arrival of the redeemer, amen."

Yair Mintzker

Yair Mintzker is assistant professor of German history at Princeton University. He is author of “The Defortification of the German City, 1689-1866” (Cambridge University Press, 2012), and is currently working on a book on the trial and execution of Jew Suess.