Ranking tech entrepreneurialism: the U.S. and Israel ahead of Europe

Rob Moffat, principal at London venture firm Balderton Capital (UK) LLP, was also unsurprised at the top-rated countries. “They are small, trading-driven countries that have a global outlook,” he said. “The average Irish or Swedish entrepreneur is global [in outlook] from day one.”

Commenting on the other end of the table, Mr. Moffat said not too much should be read into Central and Eastern Europe’s underperformance. “It is very early days still. The problem the region has is that it is very diffuse: There are maybe 20 cities that have five or 10 interesting startups in each of them.” Among leading industrial nations, Italy fares worst—just 0.07% of the European per capita average.

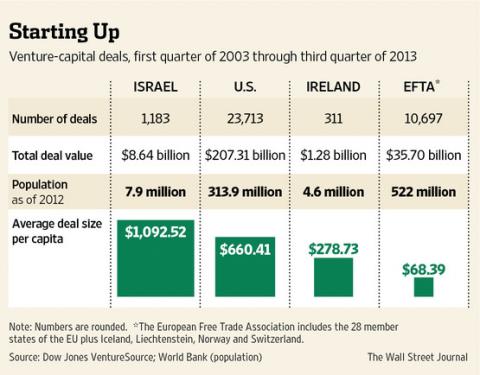

However, when we compare Europe with the U.S. and Israel, a far-from-flattering picture emerges. Over the last 10 years, on average, for every $1 raised per capita in Europe, the U.S. raises just under $10 and Israel raises $16.

Worryingly for Europe, Israel and (to a lesser extent) the U.S. are pulling even further ahead. In just the past five years, Israel has raised $23, and the U.S. just over $10, for every dollar raised per capita in Europe. In absolute terms, Israel has raised more venture money in that period than any single EFTA country, and more than the bottom 24 EFTA countries combined.

But Liam Boogar, a commentator on the French startup scene, criticized the analysis. “I am not sure it tells us very much, and what it does tell us isn’t that useful,” he said. “I am much more interested in looking at how many companies start and get a successful exit. That is more interesting and a better measure of entrepreneurial activity.”

As with all such analyses, there are health warnings. First, the very small number of deals in some European countries—single figures in many cases—means results have to be treated with great caution. Further, very small nations (with populations under one million) weren’t included on their own, but were included in the EFTA total.

And while per capita venture capital fundraising is a useful comparator, the uneven distribution of innovation in some countries, especially those in Central and Eastern Europe, may damp their performance. Poland’s startup activity is concentrated in three cities; most of the 38 million population play no role.

Lastly, the position of the U.K. may be anomalous. Many companies that originate elsewhere in Europe are registered in the U.K., inflating its performance and deflating other countries’.

VentureSource records deals from seed rounds through to late-stage funding. Fundraising rounds that include angel investors, wealthy individuals who invest directly in a startup, are counted only when the round also includes at least one venture-capital firm.

Dow Jones VentureSource doesn’t categorize companies as “tech startups,” so the figures are drawn from three of its categories: business and financial services (business-support-services and financial-institutions-and-services subcategories only); consumer services; and information technology. Dow Jones & Co., owned by News CorpNWSA -0.06%, is the publisher of The Wall Street Journal.

Ben Rooney